Traveling Boy’s Memory Lane Invites all writers to share their stories to the world. As long as websites in the internet are accessible, these stories will be your footprint of your life adventures. They may be happy, sad, playful, religious, political, narrative, poetic, etc. The more creative and the more honest, the better. Years … centuries from now, some alien ship will find this website and will wonder what mankind was all about. Your articles will answer a lot of their questions.

Part 4: The Final Chapter

Written by guest writer Frank Koo Endo in 1994

In May 1943, the War Relocation Authority in Washington D.C. ended the internment program. They handed out a guide book to all residents in relocation centers to help prepare for moving out. There were three choices concerning leaving the centers: (1) Short-term, (2) Seasonal; and (3) Indefinitely.

The younger people were among the first to permanently leave the center to attend educational institutions or to look for a place to reside and work. However, in the beginning, we were not permitted to return to the West Coast, so many people ventured to the Mid-West and East Coast.

In the summer of 1944, my brother decided to go to Chicago to resettle. The Government gave him a rail ticket, $3 per day for meals, and $50.00 for financial assistance. After waiting anxiously several weeks, my mother and I received a letter from him stating that he had found a home and asked if we would come to Chicago. We immediately requested permission to leave Amache Relocation Center permanently. My mother and I received our train fare, etc. and headed for Chicago. We had been interned for two years and four months. We were finally FREED AT LAST.

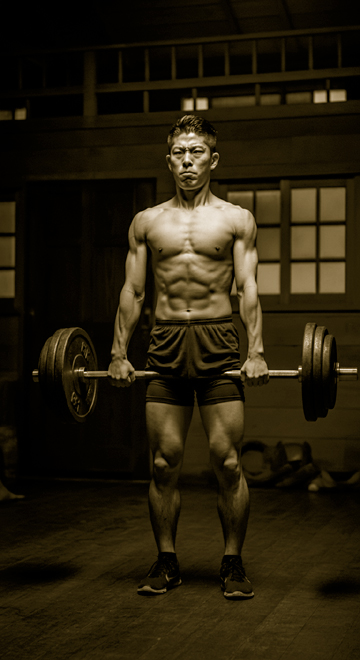

After moving to Chicago in 1944, I continued to pursue my gymnastics career, and worked out at the Hyde Park YMCA. That year, I won the Illinois Junior All-Around Gymnastics Championships held at the University of Chicago. I also wondered how I would do in weightlifting, because I started this sport at Terminal Island. That same year, I competed in the 136 lb. Class in the City, State and Tri-State Weightlifting Championships. I took second place in each of these competitions. There was another Japanese by the name of Iwakiri who always took first.

On February 6, 1945, I reported for induction into the Military Service. I took my basic training at Camp Gordon in Georgia. There were about thirty other Nisei in our Company. After basic training, I was transferred to Fort Snelling Military Language School in Minnesota, where I was accepted to study the Japanese language for the next six months. While at Fort Snelling, World War II ended. We finished our schooling, and were shipped to Tokyo, Japan. I was assigned to war criminal investigations and served as chief clerk and interpreter.

Learning to type at San Pedro High School and my parents sending me to Japanese School started to pay off. I was excited to work for America overseas. I spent two and a half years with war criminal investigation work. The Americans that spoke Japanese were in demand there in all phases of work. I remained in Japan after being discharged from the Army, and worked for the U.S. Air Force Intelligence Service as an interrogator for two more years.

The Japanese noticed my gymnastics skills while I was working out one day at the Osaka YMCA. Because of that, I was asked to be their advisor to the Japan Gymnastics Association. In 1950, I made arrangements for the United States National men’s gymnastics team to come to Japan for an international competition and to do several exhibitions in various cities throughout Japan. My gymnastics experience at San Pedro High School and in Chicago became very useful. General Douglas MacArthur invited me into his Tokyo Military Headquarters with the U S. Gymnastics Team, and we talked for twenty-seven minutes.

During my time in Japan, I fell in love with a Japanese girl. Although the war was over between Japan and the United States, no Peace Treaty had been signed yet. Therefore, Americans like myself were not allowed to marry a Japanese national. I read in the Tokyo Stars G Stripes newspaper that honorably discharged veterans in Europe were being granted permission to marry German girls under a Private Bill in Congress. This was in 1948. I pursued this route and after two and a half years, I was probably the first American to be granted permission, in Japan, to marry a Japanese and bring her to America. My wife and I drove around the United States for two and a half months, and then settled in Los Angeles.

On April 21, 1988, the U.S.-Senate voted to pay $20,000.00 to each World War II internee for the act of forcibly removing persons of Japanese ancestry from their homes and putting them into internment camps. Then, on August 10, 1988, President Reagan signed Bill H.R. 442 which put the financial reparation into effect. I received my check for $20,000.00 in September, 1991. Those who have passed away such as my twin brother and my mother, received nothing. Only 60,000 out of the 120,000 internees survived to receive payments.

It is now May, 1994. I have been a certified gymnastics judge for both National and International competitions for more than twenty-five years. I’ve served as an official at several notable gymnastics events such as the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles and the 1991 World Gymnastics Championships. I have two sons experienced in gymnastics. They both competed for California State University at Long Beach and now jointly operate a gymnastics supply business in Gardena, California, that I established 35 years ago. I have been honored with the Ko-ro-sho (Hall-of-Fame) award from the Japan Gymnastics Association for assisting their many tours to America, introducing trampolining to Japan in 1959, and obtaining gymnastics coaching positions for top gymnasts from Japan at American colleges and universities.

There were thirty six Nisei, including myself, that attended San Pedro High School in 1942 and should have graduated that summer. We received a high school diploma while we were in the relocation centers. Recently, with the help of a San Pedro councilman and the current principal of SPHS, we will finally receive our true high school diploma! Our belated “graduation” ceremony will take place on June 8, 1994, fiftytwo years afterward. We haven’t been forgotten!

I am now seventy-one years old, but I can still kick up to a handstand — the fear that inspired me to take up gymnastics while I was only a kid in junior high school.

All of the cannery homes in fish harbor are long gone. So are the church, elementary school, judo, dojo, and the stores I went to. Children don’t go swimming in the harbor anymore. There isn’t the same fishing industry there used to be. The ferry boats are a part of history now, replaced by a large, modern bridge which connects the island with San Pedro.

Terminal Island was an island in Time.

End of Frank Endo’s story.

Read Part One. Part Two. Part Three.

Read more about Frank Endo

Joseph

November 3, 2025 at 11:43 pm

Amazing story. This is the first time I read what it was like being in an internment camp. America treated you so unfairly.

Danny

November 3, 2025 at 11:56 pm

Something about the Japanese — hard working, focused, mature, self-less, much to be proud of.