By Ed Boitano

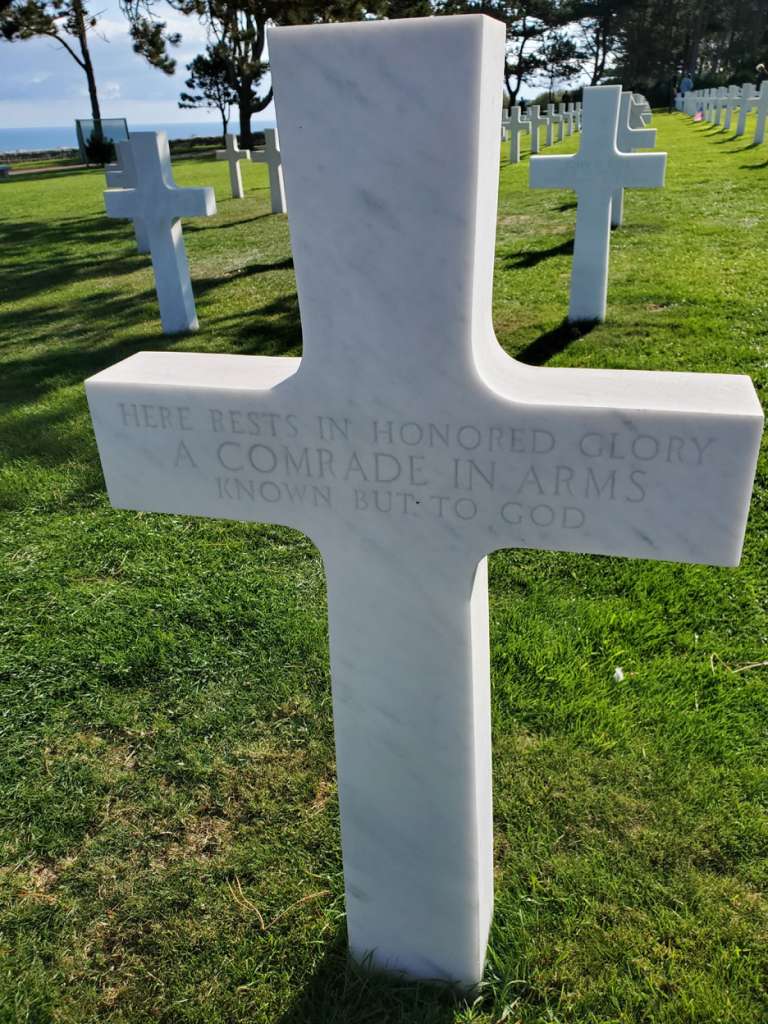

On the hallowed grounds of the Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial rest 9,387 Americans who made the ultimate sacrifice during the Operation Overlord landings and ensuing battles in the Allied liberation of France. Set high on a bluff above the Omaha Beachhead in Colleville-sur-Mer, France, it is one of the best-known military cemeteries and memorials in the world.

Part III of the series begins with a long coach ride from the riverboat AmaLyra’s docking to the Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial. Our guide explained that we would walk the cemetery alone, for she never accompanies tour groups in fear of endless bouts of tears. This I soon understood, as I paid witness to the many Latin Crosses and Star of David markers on the cemetery’s lawn. The government of France granted use of the land to the United States, perpetually, free of charge or tax to honor the Allied forces. U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower and French President René Coty dedicated the cemetery on July 18, 1956.

Elizabeth A. Richardson’s life began in Indiana, then moved on to college and career in Wisconsin, finishing with the American Red Cross in England and France in 1945. Her job was to lift the morale of GIs in rural Britain, providing food, entertainment and “a connection to home.” This was done by the use of “Clubmobiles”: single-decked buses, barely large enough to transport three Red Cross women and one British driver to GIs stationed far away in the countryside. This unique vehicle also contained coffee and doughnut-making equipment, chewing gum, cigarettes, magazines, newspapers, and a record player for popular songs and dance. The Red Cross “Clubmobileists” were well-schooled in the use of GI slang; could “dish it out and take it,” knew how to talk about baseball, Duke Ellington and the Coney Island Hot Dog. They also knew how to look at pictures of wives, families and girlfriends, and patiently listen to personal stories, which may have included sad news from home. The American Red Cross “Clubmobile” women were often referred to as “donut dollies.” When passing a truckload of GIs, a popular exchange was, “Hey, soldier, what’s cooking tonight?” The soldiers would shout back, “Chicken, wanna neck?” Elizabeth A. Richardson’s life ended in a plane crash to Paris.

As I left the cemetery, I accessed my phone and discovered that as many as 4,400 Allied troops, along with approximately the same number of French civilians, died during Operation Overlord on the day of June 6, 1944.

A decision was to be made: a self-guided tour of the Musée Mémorial d’Omaha Beach or visit the Nazi Wehrmacht (“defense power”) bunkers overlooking Omaha Beach. With only an hour and a half, it would be difficult to do justice to them both. But, after a brief moment of hesitation, I realized that my decision was obvious.

In the wave of thousands of landing ships, more than 156,000 Allied infantrymen stormed five Normandy beaches – Juno, Gold, Sword, Utah and Omaha – spread over 50 miles of blood-soaked terrain. Facing them were around 50,000 German soldiers. Like the “Battle of Okinawa” and “Invasion of the Philippines,” it was among the largest amphibious assaults in modern history.

On Omaha itself, Americans suffered 2,400 casualties, but eventually landed 34,000 troops. The German 352nd Division lost 20 percent of its strength, with 1,200 casualties, and also had problems with reserves arriving in support. The French Resistance and the Special Operations Executive (SOE), a secret British organization, had provided accurate intelligence reports and aerial photography as well as the disruption of German supply and communication lines.

So, with facts and stats in my head, I charged over to the bunkers, and took a harmless spill on its hill, which produced no laughter from the slightly older AmaLyra tour group, whose only concern was of my well-being. But my concern was to enter a bunker and see the Wehrmacht soldiers’ viewpoint of Allied troops on Omaha’s beachhead. My mind raced to images of Allied soldiers landing on the bloody-soaked beaches, doing everything in their power to stay alive, help the wounded, let alone fight. I also thought of conscripted adolescent German soldiers, barely old enough to fire a weapon, trembling, desperately trying to hold back tears. My thoughts then wandered to the words of my Marine Corp father, who had experienced his own World War II D-Days in the “Battle of Okinawa” and “Battle of Iwo Jima”: “No one wins in war, Eddie… it’s only the little guy that gets hurt. We should ask all those flag wavers in Washington DC, if they’re willing to sacrifice the lives of their own children.”

Yet, today, I’ve noticed there are some who have never experienced warfare, regard a battle as it was hardly more than a video game, while for others – my next-door neighbor, who lost a leg in Vietnam, or my two cousins, one who became a Quaker, the other who eventually found piece in Buddhism – it is quite literally a matter of life and death.

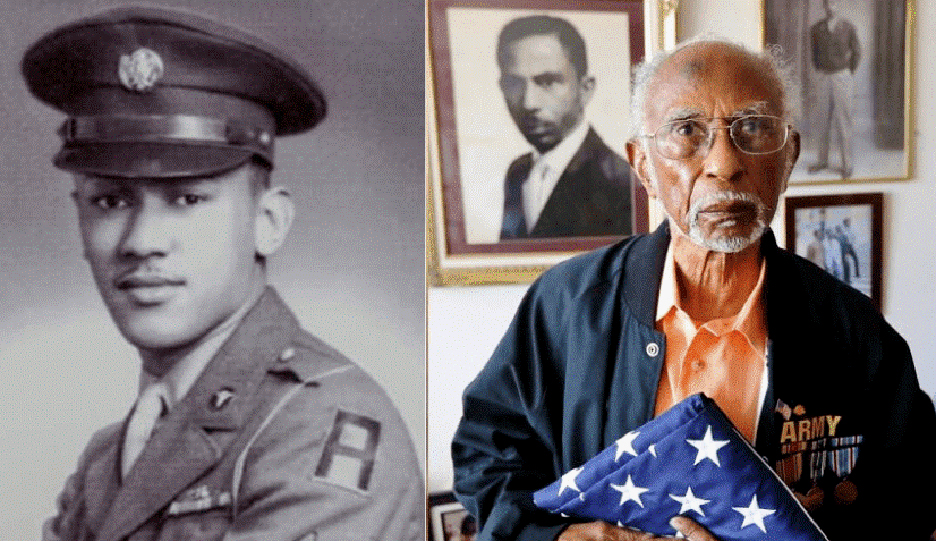

African-American soldiers accounted for a still unknown number of deaths among the 2,000 black troops who stormed the Omaha and Utah beachheads on D-Day. While portrayals in film and literature often depict all-white troops, African-Americans fought not only Nazi German weaponry, but also segregation in the military and at home. Waverly Bernard “Woody” Woodson, Jr. was a medic in the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion when his landing craft hit a mine on its way to Omaha Beach. Woodson was wounded in the back and groin, but still spent 30 hours on the beach, reviving soldiers, resetting broken bones, performing amputations, removing bullets and shrapnel before collapsing from his own wounds. By the end of World War II, more than a million African-Americans were in uniform, but when many returned to their homes in the Jim Crow South, they were not regarded as heroes; often segregated from others, denied admittance to restaurants and movie theaters, and forced to sit in the back of buses, while still in uniform, as their white band of brothers sat in the front. In 1994, Waverly Bernard “Woody” Woodson, Jr. was one of the three veterans invited to visit Normandy by the French government to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the D-Day landings. He was presented with a commemorative medallion.

As my photographer and I left the bunkers, we hurried past our tearless guide, who shouted we only had ten minutes left to access the tour bus. “What should we do?” “Run,” she replied. Nevertheless, we decided to run into the engaging Musée Mémorial d’Omaha Beach for a cursory look at its collection of soldiers’ personnel objects, historic documents, archival photographs, vehicles, uniforms and weapons, and a peek at a 25 minute-documentary film. We swore that somehow, someday, we will return for full solid day.

Our bus arrived at a small village for a closer look at Omaha Beach. In our 30 minutes, I noticed the lines at an ice cream vendor, and understood that this was also a vacation for many. I realized I was on holiday, too; as my photographer and I sipped cappuccino on a restaurant’s deck, gazing at the beach, imagining the U.S. troops’ landings and the horrors they faced.

Julius “Henry” Pieper and Ludwig “Louie” Pieper did everything together. They were identical twin brothers of German immigrant parents, the first twins to graduate from their Nebraska high school, and then went on to work for the Burlington Railroad together. When they enlistment with the Navy, underage, but with parents’ consent, they were informed that they would be separated, but their father appealed and made a special request. “My sons came into this world together, and they should have the right to fight and die together.” And when their vessel hit a German mine at Utah Beach, they perished together at 19-years-old in the LST-523’s radio control room. But then, they were apart. Louie Pieper’s body was found and buried at the Normandy American Cemetery, but Henry’s body, known only as “X-9352,” was not identified until 74 years later due to the help of Vanessa Taylor. Ms. Taylor was a student at Ainsworth High School in Nebraska, who had been looking for a topic for a class project. “We were supposed to select a silent hero from our state. I just happened to notice there were two people killed who had the same exact last name.” She made a request to the U.S. Government for personnel files on the two sailors which caught the attention of officials at the Defense POW-MIA Accounting Agency. Henry’s body was recognized by his dental records and DNA. The Pieper boys were given the Victory Medal and the Purple Heart. Inseparable in birth, in life and in death, and finally reunited. Otto and Anna Pieper received a letter from the brothers only two days before their deaths: “Do not worry about us. We are together.”

As we began our long journey back to the AmaLyra, we passed through a number of small French villages; national flags waved proudly in the sky. It was quiet on the bus. Perhaps we all felt a sense of reverance for the nations who had suffered and sacrificed; no doubt as the French did, too, and still pay homage to the Allied soldiers on this bloody day, a bloody day that time will never forget.

A member of the Coeur d’Alene Schi_tsu’umsh Tribe, U.S. Army PVT Charles K. Louie was one of the 175 American-Indian soldiers who participated in Operation Overlord. As part of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, he was killed in mid-air in the pre-dawn hours of D-Day during the paratroopers’ descent behind enemy lines. A combination of low clouds and anti-aircraft fire caused the break-up of the air armada’s formations, scattering paratroopers throughout the pitch-black sky. The name of U.S. Army PVT. Charles K. Louie is listed on the WWII Honor Roll and on the tablets of the missing at the Normandy American Cemetery, with the distinction that he was awarded the Bronze Star and a Purpleheart. As many as 25,000 American-Indians fought actively in World War II: 21,767 in the Army, 1,910 in the Navy, 874 in the Marines, 121 in the Coast Guard, and several hundred nurses. There is a deep sense of patriotism among many of the tribal nations, a belief that despite genocide, broken treaties, and the savage Anglo-American attacks of their tribes, that the United States can still be a better place for all.

As I returned to my stateroom on the AmaLyra, I slipped into a dream, and imagined the sound of D-Day Clickers. Clickers were used by the American paratroopers of the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions, who made parachute drops behind enemy lines on the blackened eve of Operation Overlord’s D-Day. Many perished in the sky or drowned in the flooded marshlands below, but those who landed safely, would make a single click, and waited to hear two clicks back, to determine if friend or foe. When I accessed mine, I noticed two clicks back.

Postscript:

The French Resistance, estimated at 500,000 men and women, carried out endless acts of sabotage against the Axis occupiers. Created by the French Communist Party in 1939, the French Resistance was made up of citizens. And, like other anti-fascist partisans, they were not protected by the rules of war. More than 90,000 French Resisters were killed, tortured or deported. But, after four years of occupation, the French Resistance staged an uprising against the German garrison in Paris, which led to the city’s liberation on August 25, 1944. Allied troops were soon to follow.

The Allies became a formalized group upon the Declaration by United Nations on January 1, 1942, which was signed by 26 nations, including governments in exile and small nations far removed from the war. Latinos from the Americas, led the Allied Western European pack with the largest number of troops in service at 16,000,000.

America First and Seven Hours in December

The U.S. was a late entry in WW II due to a pressure campaign by the America First Committe – its name taken from a Ku Klux Klan rally – whose isolationist policy included no intervention in foreign wars and virtually no immigration from non-Anglo-Saxon nations. With Charles Lindberg as their spokesperson, and members who embraced anti-Semitism and fascist sympathies among their ranks, many admired Hitler and some considered him a friend. Lindberg wore a German medal given to him by Luftwaffe Commander-in-Chief, Herman Goering, then number two man in the Nazi chain of command. The America First’s intensified campaign against sanctions dramatically impacted the U.S. Government’s policy to such an extent that the ocean liner St. Louis, whose 937 passengers were almost all Jewish children seeking safety, was turned back to Europe where many would face certain death.

a prevailing sentiment among the America First nationalists was that British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and world Jewry had caused WW II, not Nazi Germany. The America First nationalists vehemently oppose the Lend-Lease Act of 1941, which stated that the U.S. could lend or lease war supplies to any nation deemed “vital to the defense of the United States.” Under this policy, the U.S. was able to supply aid to Great Britain, while still remaining officially neutral. Once this was achieved, Churchill knew that Nazi Germany would be defeated. The U.S. finally joined the military campaign after the Western Allies had been engaged in warfare with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy for 27-months. It took the surprise, coordinated seven-hour aerial bombings on December 7, 1941 by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service on the U.S. territories of the Philippines, Guam, Wake Island and Hawaii’s Pearl Harbor for the U.S. to act. And act they did, sending a combined number of 16,112,566 American troops to Western Europe, North Africa and the Pacific.

Sad as it may sound

Despite my reluctance to use the term, “fake news,” I found the concept of “D-Day Dodgers” to be a particularly disturbing example. A “D-Day Dodger” was a name branded on Allied troops who supposedly avoided combat on Operation Overlord’s D-Day. The label was put forth by the press to an ignorant populace, unaware that there were many Allied troops who had already participated in earlier D-Days. Many were killed or wounded in the invasion of Sicily, followed by the D-Day beachheads on the Italian mainland with Anzio, Salerno, Calabria and Taranto. On the Western Front of World War II, the battles in Italy proved to the most devastating campaigns in casualties, suffered by infantry divisions on both sides. Over 150,000 Italian civilians died, as well as 35,828 anti-fascist partisans.

I encourage you to read T-Boy’s Stephen Brewer’s illuminating article which covers the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery: At Rest in Italy.

Honor the served & fallen, and teach the next generation

“The War” is a seven-part documentary mini-series which focuses on WW II from the perspective of people living in America’s towns. Directed by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, and written by Geoffrey Ward, the inspiration for the series stemmed from a lecture Ken Burns made at a U.S. high school. He was surprised that many of the students knew very little about WW II, with some believing that the war was fought against the Soviet Union; our ally who lost 28 million Red Army soldiers and civilians on the Eastern Front, yet also accounted for 76 percent of Germany’s military dead. It was the beginning of the end after the Red Army’s defeat of the German army in the Battle of Stalingrad in 1943, which continued on the Western Front with the Allied battles at Sicily, Anzio, the Battle of the Bulge, far too many to list.

And, with the Red Army at Berlin’s doorsteps, Hitler, now hidden in his bunker, issued his infamous Nero Decree for the complete destruction of Berlin, leaving no trace that a city had ever existed; also aimed to punish the German people for losing the war. Due to breakdown of communication lines or to the refusal of his generals, it was a command that was never met. Days later Hitler would take his own life. The Red Army soon poured into Berlin, leaving the Volkssturm, Germany‘s citizen army of children and old men to defend what was left of the city. But no one could stop the sheer force of the Red Army’s numbers, and Germany would officially surrender after the Soviet Union victory at the Battle of Berlin (May 2, 1945),

V-E Day celebrations erupted around the globe, but U.S. President Harry S. Truman reminded us that there was a V-J Day that still needed to come.

Related Articles

- See Part I: Down the Seine to Normandy: Seven Days on the AmaLyra

- See Part II: Monet in Giverny: Down the Seine to Normandy on the AmaLyra

- Stay Tuned for part IV where Ed Boitano writes and Deb Roskamp photographs, The Long Week on the Seiene closes: The royal residence at Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France’s Musée d’Archéologie, and the final night on the riverboat AmaLyra.

Ron Jameson

November 9, 2022 at 12:57 pm

Yes, there has been volumes written about Normandy and WWII, but I loved the way you shared your thoughts abouts the young Germans as you toured the bunkers. We always just think about the other side as enemies, not as human beings that don’t like being there anymore that our boys. They were simply following orders from a fanatic who could care less about their lives. Same situation in the Ukraine today. The world will never smarten up and quit listening to these fools who are out for their own gain. Pardon my political message, but the same things is playing out today.

The entire article, the pictures, and your way of writing brings these places to life. Keep

Ed Boitano

November 10, 2022 at 5:54 am

Thank you, Ron. Yes, it was conscripted German children and old men who made up the Volkssturm. There were also a number of battle tested vetds, often wounded and weary, who guarded the Gates of Berlin. But, no one could stop the Red Army, with its overwhelming amount of troops, as they charged past them into the city. Apparently, Hitler ordered the complete destruction of Berlin, leaving no trace that the city had even existed. Communication from his bunker never reached his generals, and we are thankful that one of world’s greatest cities remains today.