By Ed Boitano

There’s a chance I might have mentioned the name “Monet” in my previous article. Yes, the painter who a gave birth to Impressionism with his landmark painting, Impresssion, Sunrise. So, my enthusiasm was dramatically heightened upon the riverboat AmaLyra’s arrival to the small rural town of Giverny. Resting on the right bank of the river Seine, it is best known as the location of Claude Monet’s home and gardens. Many of his most famous canvases were painted during his 43 years in Giverny: Clos Normand, where its archways are entwined around colorful shrubs; Haystacks, the 25 canvas series which illustrates different perceptions of light; and Nymphéas (Water Lilies), a 250 oil painting collection of his waterlilies garden with its Japanese bridge.

The story goes that Monet noticed the village of Giverny while looking out a train window, and decided to rent a house and the land surrounding it, later purchasing both in 1890. He soon created his magnificent gardens, magnificent gardens of Spring, Summer and Autumn plants which he would soon paint. Among his favorites were roses, irises, chrysanthemums, dahlias, azaleas and wisterias; arranged in a complicated grid structure with vibrant plant combinations. Yet, while strolling through his enchanted gardens, I found no sense of complication at all, for the overall effect was harmonious, organic and life-enhancing. In essence, the gardens were paintings unto themselves, paintings that were always changing by the season.

After Monet moved his extended family to Giverny – which included second wife, Alice Hoschedé, his two sons from first marriage to Camille-Léonie Doncieux, and six children from Alice’s previous marriage – there was one thing that Monet desired to change; he became sensitive to the existence of an apple tree, which curtailed his views of the garden. Our thoughful AmaLyra guide explained that he had hoped to chop this particular one down to open his scope, but this was a problem for Alice, who adored the apple tree and its pink flowers. As the guide continued with her narrative, she pointed out a colony of alluring roses at the exact spot where the apple tree once stood. Monet had planted Alice’s favorite roses to appease her. Later, Monet and his team of gardeners, would bend the young apple trees’ branches so they would grow horizontally.

With the advent of Monet’s Japanese-inspired waterlily garden, his neighbors protested in fear that the foreign roots would contaminate their own plants and tributaries. He was already disliked by them due to his indifference in conversation and lack of concern about their own well-being. A compromise was issued where Monet’s waterlily garden would remain, but he could only access their property by paying a fee. Monet wholeheartedly agreed, as this was the very terrain he needed to pass when he wheel barrowed canvases and supplies into the surrounding countryside to paint its poppy fields, iris meadows and haystacks.

But soon another invasion was due to arrive, an invasion which would also effect the lives of his neighbors, and reshape the emotional texture of life in Giverny forever.

As Monet’s life and work flourished, several American Impressionists – Willard Metcalf, Louis Ritman, Theodore Wendel, John Leslie Breck – settled in Giverny around 1887. Drawn to its light, atmospheric rural landscapes, and the presence of Monet himself, an art colony slowly emerged. Their artistic life was accented by garden parties with Japanese lanterns, tennis games on a nearby court, and lively discussions and celebrations at Hôtel Baudy – where Monet, Cézanne, Renoir, Sisley, and Rodin once stunned admirers – which became the artistic center of the new colony. Monet was initially receptive of the arrival of the artists, but soon tired of the invasion. He was always too busy with his own projects to take on the role of an art teacher, but, due to his residence, the colony would steadily grow.

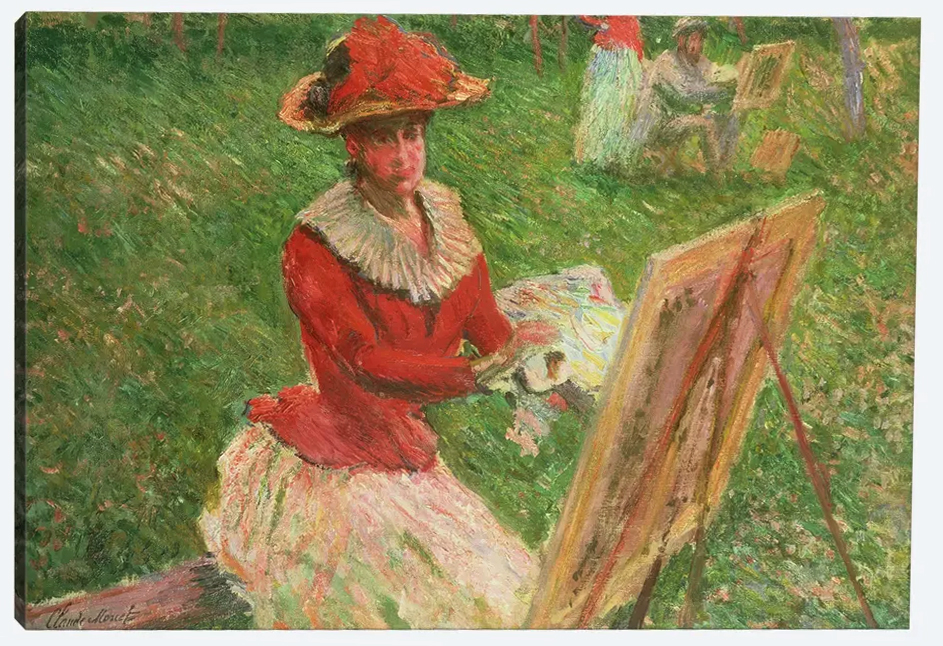

But, Monet once did become an instructor in painting. Blanche Hoschedé Monet was both his stepdaughter and daughter-in-law, due to her marriage with Monet’s first son, Jean. She was the only child in the Hoschedé-Monet household that showed a keen interest in painting. At seventeen, she became Monet’s assistant and only student, often painting beside him in the country air. She went on to become an Impressionist painter in her own rite, with exhibitions in shows and galleries. With the passing of Alice Hoschedé, Blanche’s mother and Monet’s second wife, the ageing artist suffered from intense bouts of depression and failing eyesight from cataracts. Blanche took over the household, watching over him as his eyesight was close to blindness.

Claude Monet lived at Giverny for 43 years before his death in 1926 at the age of 86; his work now highly acclaimed and known throughout the world. Blanche had passed away earlier, and so Michel, the only remaining child of Monet, inherited the 22-acre estate, and bequeathed it to the Académie des Beaux-Arts, with plans to transition it into a museum. In 1980 after a large-scale restoration – the gardens and waterlily pond were carefully replanted, Monet’s home was restored, and his large collection of Japanese woodblock prints were back on display – his home and gardens were now ready for the world to see.

Japanese woodblock printing originated in ancient China and later brought to Japan. The prints were called ukiyo-e (pictures of the floating world), and gained popularity in the mid-18th century during the Edo period. Edo was then the largest city on earth, now modern-day Tokyo; which still leads the pack today with a population of 14 million.

The artform was used to display reproduced iconic Buddhist scriptures for houses of worships, eventually followed by placements in brothels and theatres. Monet collected more than 249 Japanese woodblock prints for 40 years of his life; among his favorite artists were Kitagawa Utamaro, Katsushika Hokusai and Utagawa Hiroshige, where many are exhibited at his home today.

Monet’s house and gardens sparked a boom in tourism, with approximately 500,000 visitors each year since restoration. Giverny’s other main attractions include the Museum of Impressionism Giverny, dedicated to the history of Impressionism; the 11th century Église Sainte-Radegonde de Giverny, which requires a long walk from the village center, but you’ll see Monet’s final resting place in a tomb outside the church; the free Musée de Mécanique Naturelle (Natural Mechanics Museum); and the Hôtel Baudy, now restored in period decor, and called Restaurant Musee BAUDY, where Mrs Baudy’s omelette is still on the menu.

Monet’s Work Lives On

The painting Meules, part of Monet’s Haystacks series in Giverny, sold for $110.70 million dollars at a Sotheby’s auction in 2019. It was the first Impressionist painting to surpass $100 million dollars. And, Impresssion, Sunrise, once mocked and condemned by art critics, is estimated to be worth $250 – $350 million dollars in today’s currency.

What I learned: Monet loved gardening as much as he loved painting.

POSTSCRIPT: Camille-LéonieDoncieux

Though she never lived in Giverny, a special note should be devoted to Monet’s first wife, the sublime Camille-Léonie Doncieux. She was Monet’s favorite art model and penniless muse, then his mistress and bride, the mother of their two children, and the subject of a number of his paintings: Woman with a Parasol – Madame Monet and Her Son, Camille (The Woman in the Green Dress), Camille Monet on a Garden Bench, as well as an art model for impressionists Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Édouard Manet.

Camille Monet was far too young to pass away at 32 years of age, believed to be from pelvic cancer, after giving birth to second son, Michel. Monet was grief stricken, yet felt compelled to lock her bedroom door behind him and paint her lifeless body with the aptly titled, Camille on Her Deathbed.

Art history demands to know more about the life of Camille and her relationship with Monet, but due to the jealousy of the second Madame Monet, Alice Hoschede – who insisted that Monet destroy all mementos, letters and photos that even attested to Camille’s existence – it is still somewhat shrouded in mystery today.

Related Articles

- See Part I: Down the Seine to Normandy: Seven Days on the AmaLyra

- See Part III: From Monet Gardens to Gardens of Stone: Seven Days on the AmaLyra

- Stay Tuned for part IV where Ed Boitano writes and Deb Roskamp photographs, The Long Week on the Seiene closes: The royal residence at Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France’s Musée d’Archéologie, and the final night on the riverboat AmaLyra.

Raoul

October 20, 2022 at 9:20 am

I loved this article. I never knew Monet’s disdain for the social niceties. I love your inside story about the garden and his bouts with his wife and neighbors. Your article brings back memories of Art School where my teacher explained the rationale behind the color renditions to produce an optical illusion. Being an artist myself I didn’t quite grasp the fuss about impressionists. To me they were haphazardly done — meaning, I could whip up something like this easily (as opposed to the finished works of Caravaggio or Vermeer). In my younger days I was always in “I can do that” mode. I’d like to think I’ve matured and though I still struggle with judging pieces of art by the difficulty of execution, I have learned to appreciate the significance of what makes something great. Indeed, the impressionists have left a respectable impression with me.

Ed Boitano

October 20, 2022 at 7:45 pm

Thank you, Mr. Raoul. I appreciate your kind words and personal narrative about your life in art. It appears that I could learn much from you.