|

|

|

|

|

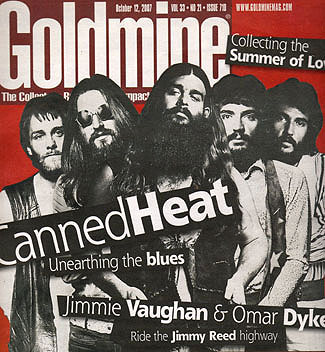

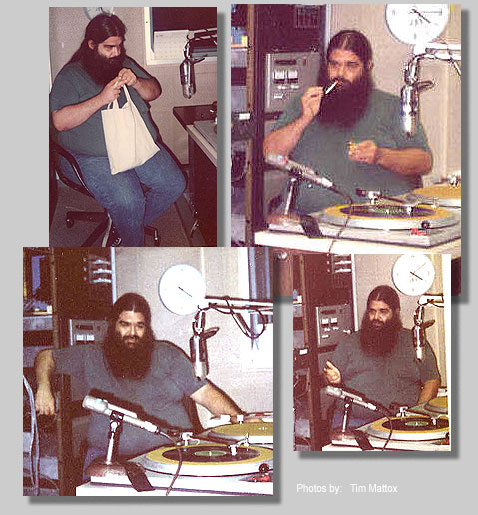

The Bear

|

|

|

BH: "On the road again. CANNED HEAT has been

together since September of '65 and has been non-stop until this

very day and where we will be appearing this evening at the club...Boogie

Woogying. TM: The same Harvey Mandel from Mayall's Bluesbreakers? TM: Prior to the formation of CANNED HEAT in 1965,

did you have any formal musical training or was your family musically

inclined?

"When I was born and just barely able to walk, I discovered records. They went around and music came off of them and it didn't really matter to me what was on the record. It could be Caruso, it could have been Fritz Chrysler, Glenn Miller or Benny Goodman or whatever, I was just fascinated by records. So rather than get little toy cars and things to play with, like most kids, I wanted records. I was shining shoes at age five so I could get enough money to buy records for my collection. Our church had an old folk's home and when they finally got a new hi-fi set, they gave me like three hundred 78's that they had. I kept accumulating them. By the time the 1950's rolled around, my father was no longer a bus driver. He was working for a computer company and was transferred to Denver. Three-quarters of the weight for our move was my records. I was never much of a student; I hated school and never gave much thought on what I would do tomorrow. I just lived for the day and played my records. When all the other guys were out working on their cars, taking chicks out on dates, to the prom; I was out hunting for phonograph records." JOHN FAHEY "I met John Fahey, who is a very good

country blues guitar picker and he's also a scholar on the blues.

We struck up a good friendship. It was a lot of fun playing record

and swapping stories of different blues singers. I borrowed a

tape from him and he disappeared for a year and I didn't see him.

This was about 1965 and I'd gotten a job in a record shop in Westwood,

California. This guy came in that I'd never seen before, and said,

'Are you Hite?' I went, 'Yeah!' He said, 'Fahey wants his tape

back.' I said, 'Sure, where is he?' The guy said, 'He was in Louisiana,

but he's back now and he wants his tape back.' HENRY VESTINE "I called up Henry Vestine who was

a friend of mine and said, "I've got a band and you've got

to come hear us. We played last night and we're playing again

tonight, come on down'. He (Vestine) at that time was playing

with the Mothers of Invention, Zappa's Group. He said, 'Alright,

I'll come down.' I laid around watching soap operas all day and

listening to my mother holler at me to get a job. I got a phone

call from Frank Cook who said, 'Hey, would you like to play a

gig for old time's sake, just for the heck of it?' I said, 'Sure,

where?' He said, 'At UCLA at ten o'clock in the morning.' I said,

'Ten o'clock in the morning? Nobody plays a gig at ten o'clock

in the morning!' He said, 'I'm having a happening.' He (Cook)

was in the theatre arts section at UCLA. And at this time the

psychedelic happenings in San Francisco had just started with

the Fillmore and the Avalon, with all the light shows and the

smoke and the craziness. He was going to reproduce that at UCLA

at ten o'clock in the morning.

"That (song) was released, the A side of that was 'Boogie Music.' That's the one that we thought would be the hit. We left on our very first tour, a six-week tour of the United States. We were sleeping in other bands houses, on floors, in kitchens or wherever we could find a place to stay. I remember we came into Cleveland, Ohio and I had 35 cents in my pocket. We called our manager to tell him things were going relatively well, but we were broke. He said, 'Well, you won't be broke long because some disc jockey down in Ft. Worth, Texas turned over 'Boogie Music' and 'On the Road Again' was number one on their charts and was being played around the country.'

"We didn't want to go. We'd been playing

a job at the Fillmore West and Henry had a confrontation with

Larry, our bass player, on Friday night. Saturday afternoon our

manager came up to San Francisco and said, 'Ok, CANNED HEAT has

a gig tonight at the Fillmore. Whoever's in CANNED HEAT, be there.

And Henry didn't show up. We searched around madly for a guitar

player. Mike Bloomfield was hanging out, so he played the first

set with us. (He) apologized for not being able to stay and said

he had to go. Over in the corner of the dressing room was Harvey

Mandel. We said, 'Hey man, you want to play the gig?' He said,

'Sure' and played the second set with us. When the set was over

we said, 'Look, we're in the middle of a tour and we need a guitar

player, are you doing anything?' He said, 'No.' We said, 'Go home

and get your suitcase packed because we're going to New York at

six o'clock in the morning.'

"Alan, we, to this day really don't know

what Alan's main problem was. I had my own ideas. He was never

one to play for the people. He never really cared what the people

thought about how we played. He was trying to play for the rest

of the guys in the band. His words, 'I care what you guys think,

I don't care what they think.' THE COLLECTOR "I have about 2000 albums, but I have

about 78,000 singles, 45's and 78's. And that's an estimated count.

Usually when someone asks me that question in my home, I always

say, 'would you care to count them?' They always say, 'no.' Well,

neither would I.

"Of all the rhythm and blues artists, when I was very young, eleven, twelve years old back in the early 50's, it was Fats Domino that I really liked. Always liked his music. Not only Fats Domino, but Joe Turner was another big influence as far as rhythm and blues stars were concerned. And then you get back into the older stuff, I've always liked the shouters, the hollerers. There was one called Peetie Wheatstraw, the Devil's son-in-law; I really liked a lot.... and John Lee Hooker."

"We cut our second album in Chicago in 1968, I believe it was. And Calvin Carter who was vice president of VJ Records, previous to that, was our producer. We were in the studios and he said, 'Play something so I can get a level on the instruments. So Alan started playing the John Lee Hooker boogie. About three minutes later he pushed the cue button and said, 'Stop, that's great, let's record that.' That's how the boogie was born.....it was an accident. We record the boogie, the 'Fried Hockey Boogie' and it came out on the second album. It was always something that we wanted to do, was to get together with John Lee Hooker and make an album. We could never find him. One day in the airport in Portland, this was about 1969, maybe early 1970, and there he was. We went up to him and he saw us and he was coming up to us and before we had a chance to get anything out other than, 'Hello,' he said, 'I want to make a record with you guys.' Which was exactly what we wanted to say to him. The idea was born, we got numbers how to contact on another and after our tours were over we got together and Hooker n' Heat was born." THE FUTURE "If I knew that, I'd just be rolling in the dough. It's hard to say, it really is. New Wave, I mean I know a couple of New Wave groups back in Los Angeles that are doing exactly the same thing that we did in 1966. There's a group called the 'Blasters,' they're all record collectors. They love old blues, they love rhythm and blues and old rock-a-billy records and that's all they do. They're re-arranging old rock-a-billy and blues tunes and doing the same thing we did and they're calling them New Wave because they wear suits. That seems to be the thing, either wear suits or look weird. Well, we looked weird too, so what's the difference? We STILL look weird. In a telephone conversation back in 1988, Larry

Taylor, the long-time bass player for the HEAT and a fixture as

an L.A. studio musician, had these recollections of his days in

the group. "I joined the band in late 1966, early 1967 and

played from then to 1970. I left in 1971 and went back around

1978 and played another year and a half to two years." |

I was there at the Shrine to see Bob come in riding on a baby elephant. He says in the interview it was either '68 or 69: it was both – it was New Year's Eve. Debbie Hollier, Nevada City, CA * * * * Who else played with Canned Heat and Deep Purple at the Shrine in '68? Bill, LA I think the Shrine show on New Years in '68, where Bob Hite rode out on the elephant, also featured Poco, Lee Michaels, Black Pearl, Love Army and Sweetwater. Don't know that Deep Purple was booked on that evening. Bill, maybe you're thinking about the International Pop Fest in San Francisco a few months earlier that featured these fine folks... Procol Harum, Iron Butterfly, Jose Feliciano, Johnny Rivers, Eric Burdon And The Animals, Creedence Clearwater Revival, The Grass Roots, The Chambers Brothers, Deep Purple, Fraternity of Man & Canned Heat or possibly the following year in Jan of 1970 when Deep Purple appeared with Canned Heat and Renaissance on a triple-bill in London at the Royal Albert Hall. One final note: The Johnny Otis piece didn't mention it, but it was Mr. Otis that took Canned Heat into the studio the very first time to record in 1966. Small world, ain't it? Tim * * * * Thank u for posting it! Bob is still boogin' around!! Stefano Di Leonardo, Fisciano (Salerno, Italy) * * * * Great Read! I will post it on Bob "THE BEAR" Hite Official Facebook Page, Dave Tohill, Brandon, UK * * * * Hello Tim, thank you so much for letting a huge Canned Heat fan check out this interview with the Bear. I really enjoyed it. Best regards, Rick Caldwell, Fairfield, Ohio * * * * I knew Bob Hite in the 60's. Canned Heat played at our high school prom 1966 Rexford High. The Family Dog, Chet Helms, Skip Taylor. Max Kalik, Los Angeles, CA  |

This site is designed and maintained by WYNK Marketing. Send all technical issues to: support@wynkmarketing.com