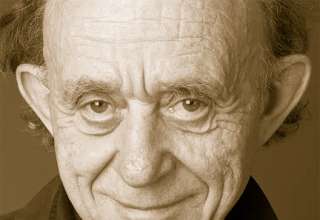

Forget Kevin Bacon; let’s play six degrees of Kenny Neal. As a 21st Century performing artist, Neal is your direct connect with all things blues; starting with family, friends and the early masters through juke joints, bars and clubs from Moscow to Madagascar…oh, and let’s not forget his award-winning theater debut on Broadway. Kenny Neal is a proven, renewable energy source with a lifelong catalogue of music to show for it.

The oldest child of legendary singer/songwriter and harmonica player Raful Neal, Kenny grew up around some of Louisiana’s most recognizable names in the genre. Lazy Lester, Buddy Guy, and Slim Harpo were just a few of the artists that frequented the Neal household, so going in you know his DNA is a vivid shade of blue. When questioned about literally being born into the blues, Kenny just smiles as he shakes his head. “That’s right; I don’t even remember learning how to play.”

Was there ever a time you wanted to do anything other than music? “No, I wanted to play music. You know I wanted to do what my dad was doing around the house with Slim Harpo and Buddy Guy and all of them guys.”

Let’s start with how music, especially blues music seems to be handed down from generation to generation, player to player. You learned it from your dad and his friends and now some six decades later, you’re doing the same thing, with people like Kingfish…“Passing the torch!” Kenny says. “Well, it’s something that helps us out throughout life. It started when the older folks used to go into the room and pray. And get on their knees and they had a spiritual thing about it. In the blues, that’s where it comes from. My grandfather was a Baptist preacher, the Reverend Raful Neal and my dad was Raful Neal, Jr. but he didn’t go into the ministry. My grandfather used to say, ‘Oh Lord, help me’ and my dad used to sing, ‘Oh Baby, help me.'” (laughing)

That sounds a lot like Big Daddy Kinsey and his family. “My dear friend, man! I knew him and all the kids. Big Daddy was one of my favorite guys, man. He was so soulful, passed it down to Donald, Ken and all those guys.”

Did you know Eddie ‘Cleanhead’ Vinson? “Eddie ‘Cleanhead’ used to come to Toronto back in 1980 and play with my band as a guest. I used to pick him up from the airport and he’d come and play for a whole week. When I finished with the Buddy Guy band, I left home in ’76 and I was the bass player for Buddy Guy and Jr. Wells and then in 1980 I decided to put the Neal Brothers together and got a house band in Toronto. I married a Canadian girl and I would bring Eddie ‘Cleanhead’ Vinson up to play with me for the whole week. And he was just the gentleman and we had such great times together…” Kenny breaks into song. ‘Women’s call me Cleanhead!’ (laughing) “That’s my boy! He had a brother that looked identical to him that worked in the L.A. airport and I was passing through and went over to the bar and said, Hey man I want to tell you, you look just like Eddie ‘Cleanhead’ Vinson and he said, ‘That’s my brother!’ (laughing) And I met his brother at the bar in LAX. And he looked exactly like Eddie.”

Your whole family was musical. “Yes, I’m the eldest of ten, seven boys and three girls. A few are now deceased. We all just played music and that was it. Around the house it was drums and guitars and we used to sit on the front porch and pretend we were on tour. We had our chairs set up and we had an uncle, as the driver. We’d say, okay we’re stopping off in Chicago, now. We’d get off of our chair and walk into the living room, the band would set up and we’ll play a gig in Chicago. We’d get back on the bus and say, okay we’re going to New York.” You were playing at what would become…your life. “I ended up doing it!”

You had a brother that played with James Cotton. “Noel, my fifth brother down from me and actually, I hooked them up. I was in Chicago in ’76 and got to know all these guys, Muddy Waters, James Cotton and Junior Wells…Eddie Clearwater, Son Seals and all those guys. Well, James was looking for a bass player and I said ‘Hey, give my little brother a call; Noel. I think he can handle it.’ And Noel stayed with him over thirty years.”

Isn’t that the same thing that Buddy Guy’s brother, Phil did for you? “Yeah, it was the same thing for me. In 1957, Buddy Guy was in my dad’s band in Baton Rouge. When Buddy went to Chicago, my dad had just started the family so he couldn’t leave home. When Buddy went to Chicago, my dad put Phil Guy in his (the Raful Neal) band after Buddy left. Then Phil went to Chicago because Buddy sent for him. And nineteen years later, Phil sent for me. It just went around in a circle.”

How did that change your trajectory once you joined Buddy Guy’s band? “I was playing with my dad since I was six or seven. Playing little juke joints, back then I was doing James Brown with my little James Brown boots, I had my pants with the stripe down the side and the tuxedo, you know? They used to set me up on the bar and I’d do my James Brown act with all the dance moves and when I finished doing my two or three songs, they’d put me back outside in the car and I’d have somebody sit with me till my dad finished the gig. He wouldn’t let me stay in the club the whole time. I was maybe seven or eight years old. I used to go home with more money than the band, cause everybody would say, ‘Oh, you’re so cute, come here and put this in your pocket. I’d have two pockets full of money.” (laughing) “Then I realized I could make money doing this too.“

“When I left home at 19 with Buddy Guy and got to Chicago, what amazed me was there was so much happening. Louisiana was slow compared to the big city. So on a Monday morning I could go to the Checkerboard Lounge, which was Buddy Guy’s club and it would be packed at 10 o’clock on a Monday morning…Blue Mondays. I’d go, Wow man look a-here, it’s like a Friday night in here on a Monday morning. And then I would meet guys and they’d tell me, I’m going to Europe with my band; Germany and France. I thought how can I get a piece of this? So, I started paying more attention, I better start writing my own music and get me an album…I had been around my dad when he was writing his songs and I had been in the studio with my dad recording when I was a kid. I had recorded some of his 45s playing bass. So I started putting my lyrics and stuff together, got me a guitar and didn’t want to see the bass anymore. I’m going to get me a guitar and put me an album together and get a piece of this pie.” (laughing) “Moving to Chicago did that for me.”

I get you grew up performing in bars and around a lot of musicians, but working with Buddy Guy and Junior Wells, playing bass at 19, weren’t you just a little intimidated? “I just wanted them to be proud of me, because I was a homeboy and I didn’t want to let them down, or let my dad down, so I put in 150% every night.”

Talk a little about your first gig playing with Buddy Guy? “I was playing music one Friday night in Baton Rouge and Sam Guy, another brother of Buddy’s walked up to me a put a piece of paper in my pocket. When we took a break it read, ‘call Buddy Guy.’ Call Buddy Guy, I wonder what he wants from me? So I called him…collect.” (laughing) “He said, ‘Look, I’m playing at Antone’s in Austin, Texas on Tuesday. I’ll talk to your dad, but Phil tells me you’re a good bass player and I’d like for you to come and play with me.’ He said, ‘If you can get your suitcase packed.’ I said what suitcase? I’d never seen a suitcase.” (laughing) “I got on a Greyhound bus that Monday and rode to Austin, Texas and Tuesday met with Buddy and Junior and went in to play with them. They started calling out all these songs my dad had been doing and prepping me with all those years. I knew their repertoire. And it was piece of cake. I went in that night and played like I’d been with the band full time. I was already a seasoned player. I was ready.”

We have to talk about your productivity. How many albums now, 18…20? “I stopped counting, man.” (laughing) “I have a lot of music out there.”

One I really want to discuss with you is the Tribute Album for Slim Harpo and your dad, Raful Neal. “Well, I wanted to preserve a piece of history when I did that. It wasn’t about me putting an album out and hoping that it would hit or something. I got all the guy’s that were left, the remaining players from Slim Harpo’s band are on that album. I went back and got Rudolph Richard, I got Mr. James Johnson and I called them up. And they go, ‘Aw man, you want me to play? I go, Yeah, because you guys recorded these songs so I need you all there. And I want you all to sing on it as well. So, I just kind of let them do their thing and you know what man, when I play that album now, I’m so happy I did it. I preserved it, I preserved it.”

I recently saw a quote from B.B. King and immediately thought of you. B.B. said, ‘I wanted to connect my guitar to human emotions.’ “I do that every night!” Kenny tells me. “I knew B.B. well; we toured all over France together, Germany…Japan. He was a great guy. I just did a new album that’s coming out in 2025; I pulled all of my brothers back together and I went to the B.B. King museum in Indianola, Mississippi and it’s called the Neal Brothers ‘Live at Club Ebony.’ It’s going to be out in February.”

Do you have any favorite memories of B.B.? “I was opening for him in Japan and I was thinking B.B. is back in his dressing room getting ready for the show, after I finish with my set and I looked around and he was standing there watching me. After I came off stage they said Mr. B.B. wants to talk with you, Mr. King wants to see you. ‘Oh shit, I hope I didn’t do nothing wrong. He said, ‘Come on in, Kenny.’ He said, ‘I love your songs, and I heard you do a couple of covers but stick with your own stuff. Every time you did one of your songs, man I enjoyed it. I don’t normally do this, but I want you to get your guitar and come up and play with me. You are an exception to the rule, so I want you to come up. And I’ll never forget that. So, I went up and played with him and from that night on every time we got together we would sit down, I would jam a song on stage and play. We became real close friends after that. He was the King!”

So many albums now, what really stands out for you? “When I got my record deal, the deal I made with the company was, if you do my dad’s tribute album first, I’ll give you an album. I just felt that my dad put all of this in me and he had never had an album before. So, I wanted him to get that before I was ready to go out and do my thing. And the record company said, ‘you got a deal!’ So I flew my dad over to Orlando, Florida a little town called Sanford at King Snake Records and I produced the album on my dad and then my record ‘Big News from Baton Rouge’ which was ‘Bio on the Bayou’ at first. Alligator picked it up after that. But I did my dad’s album first and I’m so happy I did that. It was just out of respect, I just felt better about going into my career by doing that. It’s called Raful Neal ‘Louisiana Legend.’

Can you talk about your creative approach to your blues? Do you write with an instrument? “No, I record all my music first, then I go out on the ocean or out on the water somewhere and I listen to my instrumental tracks. And the tracks talk to me, they tell me if it’s ‘Bloodline.’ I can’t sit down and write a song. I need my groove and I need to sit down and figure my music out. And then I go, man that sounds like the truth hurts. And I’ll sing about the truth hurting. Blues keep chasing me…the music talks to me, the music writes my lyrics. I don’t know how I come up with these changes in the music, but it comes out of me before the lyrics.” (laughing) “I can’t explain where it comes from.”

And it’s a universal language…“I speak to many people through my guitar. They can feel what I’m doing.”

Do you think being ‘on the water’ is because of your Louisiana up-bringing? “No, I would find when I record in Florida, my manager had a nice boat we would take out. I was just in my zone when I hit the water…and sitting out there. Throw a hook out in the water and hope I can catch a fish, sit there and play back the songs and write lyrics.

A lot of times now, in the last ten years when I pick up my guitar, sometimes I just hit record because I’ll play something I’ll never play again. And I start losing so much of that, I better capture some of this. When I get up in the morning and grab the guitar, I don’t say I’m going to play something; I just grab the guitar and start picking. Man, if it’s sounding good I’m going to forget this, I better get it down now.”

Let’s talk a little about the acting career and your work on Broadway. “I have to give credit to Taj Mahal for that because he recommended me. He was in New York and they were talking about bringing this play that Langston Hughes and Zora Hurston wrote back in 1930. They were looking for a younger actor who can sing the blues and were having a hard time doing that. So Taj said, ‘well they got a guy down in Louisiana, Kenny Neal. You should check him out, he’s a young, great blues player and maybe ya’ll could teach him to act.'” (laughing) “And that’s exactly what they did. They gave me a theatrical coach, Novella Nelson. She worked with me for three months, man. I went to read for them at the Lincoln Center and I told my manager when I came out, it’s a lost cause man. I’ll never make it.” (laughing) “But the good thing about it is Albert King is playing at the Blue Note tonight!” (laughing) “So we went to see Albert King play. But when I got back to the office in Florida and about two weeks later they called me up and said, ‘Congratulations, you got the part. So then I had to shut my music down, go to New York and go to work.”

What a thrill to work on a Broadway stage. “You know what; I won the Theater World Award for the most outstanding new coming actor.” Is there a chance we may see more from Kenny Neal on the Broadway stage? “Maybe.” Kenny just smiles. “I’m still on a mission with my blues. Broadway, you’ve got to have the discipline, man. It’s no joke on Broadway.”

You’ve collaborated with a lot of younger blues players. “Just trying to pass it along to the younger kids.” Kenny says and then speaks about his work with Christone Ingram on the song, ‘Mount Up on the Wings of the King.’ “That’s right, me and Kingfish. The album is called ‘Straight From the Heart.’ I brought in a lot of people from the Buckwheat Zydeco band and doing a song called ‘Louise Ana’ and it’s about as country and Louisiana as you can get.”

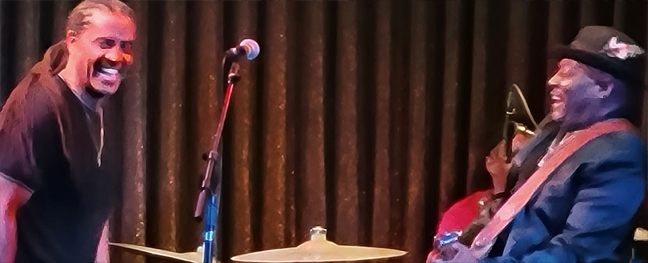

Kenny Neal live at the Montreux Blues Festival

Let me ask you about some of your friends. Billy Branch. “When I hear about Billy, I can see him now in 1976 standing against the wall, taking it all in. He wasn’t known at all, but he was a young kid with a back pack and he was just like a sponge. He was watching James Cotton and Junior Wells was his man. Billy and I won Best Acoustic Blues Album of the Year for ‘Double Take.’

Lucky Peterson. “The Best…a genius. I got my album before he did, so I set it up for his first album. I told Bob (Greenlee) if we get Lucky down here the record is going to come alive. So we flew Lucky in, I already knew Lucky from when he was with Little Milton Campbell and Bobby ‘Blue’ Bland. And you know what? For the next 12 or 13 albums, Lucky was on every one of my albums. I just didn’t feel right to make one without him.” (laughing) “Judge Peterson!”

Talk a little about the Downchild Blues Band. “It changed things for me big time. I was the house band in Toronto after Buddy Guy. And I would bring Buddy in for a week; bring Big Mama Thornton in for a week, then Phil Guy in for a week. Sunnyland Slim and all the old guys from Chicago, Cleanhead came in. And Downchild was a big band back then and they came to me and said, ‘Hey man we’re looking for a guitar player for our band, would you be interested?’ I go, Yeah man. So I joined the band and they toured all over the country in Canada and one night the lead singer of the band got pissed off and stormed off in front of thousands of people and left the gig. Donny, the band leader said, ‘Hey Neal can you sing the next set, so we can get through it?’ I said, sure man. So I went out and did the next set with the band singing and playing. The next day he said, ‘Would you be interested in being the lead singer for my band?’ I said under one condition. I’ll do it if you call it the Downchild Blues Band featuring Kenny Neal. That was enough of a deal for me right there. I didn’t care about the money, because my name would be in big lights, right at the top. I wanted to get my name out there and it was my time. So they groomed me for a front man.”

You worked with Junior Wells a lot. “He was like an uncle. When I think of Junior Wells, I think of an uncle because when I got to Chicago he was the one who took care of me and showed me the ropes. Took me to the Maxwell Street Market area and bought me clothes.”

Muddy? “Muddy! I got the chance to sing ‘Mojo Working’ with him one night and I was so happy that I forgot the words. You know there ain’t many words in ‘Mojo Working.'” (laughing) “I’ve got pictures of Muddy Waters with my son, who is 45 years old now. But I have a picture of him when he was two years old giving Muddy a big hug. When he got big enough to understand the blues he said to me, ‘Dad, I didn’t know I knew Muddy Waters.'” (laughing)

Big Mama Thornton? “Aw, she was a handful. She used to drink gin and milk…in a quart jar. I would bring her up on stage and she would sit down and have a stool next to her chair and she would drink out of this quart jar, a mason jar half milk and the rest of it gin or vodka and ice. When she got halfway down that’s when you started having trouble and she’d be yelling at the band. She did it so much my fans would say, ‘Big Mama going to fuss, tonight?'” (laughing) “They were looking forward to it.” (laughing) “You know I supported her up until the end, till the end of her life. I would get her three-piece suits, pin stripe suits. She was fun, man. I have some nice video of me and her together.”

Lazy Lester. “When I think of Lazy, I think of Baton Rouge and home. Lazy Lester used to do room and board at my grandmother’s house and he would tell me all about my folk’s way before my time. He knew my grandmother and my grandfather, my mom’s maiden name and everything. He was family and another one that I stuck with till the end. He carried his harps in a lunch pail, a fishin’ tackle box.” (laughing)

Lightnin’ Hopkins. “Lightnin’ every time he ended a song he say, ‘That’s what I’m talking about!’ We used to play, I was the bass player, Lightnin’ on guitar and we had a drummer and every time he came into Canada he’d go, ‘Where my homeboy? I want my homeboy to play!’ I got to play with Lightnin’ all the time…soulful, man.” Kenny breaks into song. “Goin’ down to Louisiana, gonna’ find me a mojo hand. Yeah, he was bad. I was lucky to share the stage with him.”

Aaron Neville. “I’ll tell you a story about Aaron. We used to play Tipitina’s all the time and I would open the show for the Neville Brothers but they never gave me anything in my dressing room, so we would sneak over into Aaron and them’s dressing room and eat up all the Popeye’s chicken and get a drink. They’re not here yet, man!” (laughing) “You better come over here and get yourself some food! We laugh at it all the time now.”

Bonnie Raitt. “When I think of Bonnie Raitt, I don’t think of her as Bonnie Raitt now. I always see her in a 1976 van, her and Freebo. She was on acoustic guitar and he was playing that tuba thing and they were opening up for Buddy Guy every night. So I saw Bonnie traveling up and down the highway way before she hit and became Bonnie Raitt. She hit later but that’s what I remember from her. She was a soulful and down home. She was one of us, man.”

Do you know Rory Block? “Yeah, I know Rory! I had a night club in Baton Rouge when I moved back from Canada, and it was called Neal’s Place. So I was calling up people across the country that I knew to come down, stop in and play for me. This place was in the hood, man. So, I hired Rory to come and play. Then I forgot about it, I forgot I told her and I don’t know how it happened, I was trying to get myself together when I was moving back from Toronto and I’m in the club and there’s this little white girl saying, ‘Hi, I’m Rory. Hey Kenny… I go, ‘oh Shucks, I’m so Sorry!’ And she goes, ‘No, no this is so wonderful, because I’ve been playing seven nights straight, I need a break…no worries, no worries. Now when I go to the Blues Music Awards we always embrace when we see each other. That’s my girl.”

Your music, you truly speak an International language and your blues road out of Baton Rouge has been phenomenal…Japan, Russia… “St. Petersburg Square, Moscow, I’ve been all over. Australia and eight countries in Africa…Rwanda, Madagascar, Burundi, Uganda, Kenya, and I’ve been all over Turkey. I’ve played Lebanon, Beirut…and I hate to see what’s happening now. I used to play at a place called Louie’s and man; they had the best fried chicken down there, they know how to fry chicken in that town. I was in Israel just before the pandemic. I’ve been about everywhere…guess I’ll just go back to Baton Rouge.” (laughing)

You’re giving back to the music community from your recording studio… “Yeah, I’m bringing musicians who can’t afford to pay the prices for studio time. I have a place to stay and let them record and pay the engineers, just to help out and give back, man. I open my doors for that.”

What’s coming up next for Kenny Neal, any new projects? “I have a new single coming out with my youngest son, Michael called ‘Devil in the Delta.’ It’ll be out on Sony Records at the start of 2025.”

Kenny Neal is without doubt…gifted; but it’s his positivity and consistency that shines brightest. He strives for excellence in everything he pursues and that’s reflected in the Grammy nominations and a whole host of Blues Music Awards. And much like the legends that preceded him, he continually gives back to those who follow in his musical footsteps. What he calls, ‘passing the torch.’ Whether providing opportunities, invaluable studio time or production assistance, the man never stops helping others along their blues road. If there is such a thing as Karma, I’d suggest you stand as close as you possibly can to Kenny Neal. At least that’s what I’m thinking!