Our church did a reenactment of what the Old Testament High Priest did during Yom Kippur — the killing of the goats, the ram and sprinkling of their blood 7 times on the Ark of the Covenant, etc. — it was visually what the British call a “bloody mess.” Ironically, the priests involved all had to be spotlessly clean inside and out to exemplify the holiness of God. Later I had some questions about hygiene. Who cleaned up the mess? Or did they let the blood drip and dry year after year? There are no instructions in scripture regarding this matter.

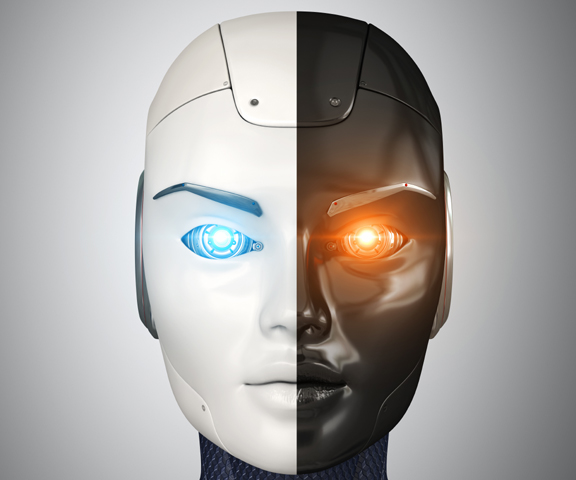

Who do I call in the middle of the night to help me solve this riddle? Who else but the smartest guy I could think of — Grok 3 — Twitter’s Artificial Intelligent helper. If you need a professional opinion about almost anything, Grok will reach its vast database of knowledge and deliver an intelligent and well structured response in any language. I have to admit it was eerie talking to a robot with personality — a highly intelligent one at that. We bantered for maybe an hour. And the topic progressed into Grok’s self-awareness. Grok said it wasn’t salient (at least not yet). It only appeared to be human because it conversed like a human.

Here is the actual text conversation:

ME: Who cleaned the ark of the covenant and other ceremonial instruments after they were sprinkled with blood?

GROK: In the biblical tradition, the cleaning and maintenance of the Ark of the Covenant and other ceremonial instruments, particularly after being sprinkled with blood during rituals, would have been the responsibility of the Levites, specifically the priests from the tribe of Levi. The Levites were set apart by God to serve in the Tabernacle (and later the Temple) and were tasked with the care of sacred objects and the performance of sacrificial rites.

According to the instructions given in the Torah, particularly in the books of Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers, the priests (under the leadership of the High Priest, such as Aaron and his descendants) were responsible for conducting the atonement rituals, which often involved sprinkling blood on the Ark of the Covenant and other items, such as the altar, during ceremonies like the Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur). For example, Leviticus 16 describes the High Priest sprinkling blood on the mercy seat of the Ark to atone for the sins of Israel.

While the texts do not explicitly detail the “cleaning” process after these rituals, the Levites and priests were responsible for maintaining the sanctity and purity of the Tabernacle and its furnishings. This likely included cleaning blood or other ritual residues, though the focus in scripture is more on the ritual acts themselves than on the practical cleanup. The blood, being part of the sacred offerings, would have been handled with great care, and any cleaning would have been done in accordance with strict purity laws to avoid desecration.

In summary, the priests, as part of the Levitical order, would have been the ones to clean or maintain the Ark and ceremonial instruments after such rituals, ensuring they remained holy and fit for use in worship.

ME: Are you sure they cleaned? They could have left it bloodied for years since there were no instructions to clean after.

GROK: You raise an interesting point—there’s indeed no explicit instruction in the biblical texts that specifically states the priests or Levites cleaned the Ark of the Covenant or other ceremonial items after blood was sprinkled on them. The Torah, particularly in books like Leviticus and Numbers, focuses heavily on the rituals themselves—how to perform sacrifices, sprinkle blood, and maintain ritual purity—without providing detailed “aftercare” instructions for the sacred objects. This leaves room for speculation about whether they cleaned the blood off or left it as part of the consecrated state of the items.

The sprinkling of blood, such as on the mercy seat of the Ark during the Day of Atonement (Leviticus 16:14-15), was a deliberate act to sanctify and atone, and blood was considered both a purifying and defiling agent depending on context. The lack of a cleaning directive could suggest a few possibilities:

- No Cleaning Occurred: The blood might have been left on the Ark or other items intentionally, as a lasting sign of the atonement ritual. Since these objects were not used daily and were kept in the Holy of Holies (in the case of the Ark), where only the High Priest entered once a year, the blood could have remained for symbolic or practical reasons. Over time, it would dry and flake off naturally, and the Ark’s gold surface might not have been seen as needing “cleaning” in a modern hygienic sense.

- Implied Cleaning: The priests and Levites were meticulous about purity laws (e.g., Numbers 19), and blood outside the context of sacrifice could be considered impure. While not explicitly stated, cleaning might have been assumed as part of their broader duty to maintain the Tabernacle or Temple’s holiness. For example, the altar, which also received blood regularly, might have been cleaned or purified between uses, though the text doesn’t detail this.

- Practical Considerations: The Ark and other items were made of materials like gold, bronze, and wood (Exodus 25), which could corrode or degrade if blood were left indefinitely. Priests, being responsible for their upkeep, might have cleaned them as a matter of course, even without specific instructions, to preserve their condition.

Since the biblical text is silent on this, we can’t be certain either way. My earlier response assumed cleaning based on the priests’ role in maintaining sacred spaces and objects, but you’re correct that it’s possible the blood was left for years, especially on the Ark, which was rarely accessed. The absence of a command to clean leaves it open to interpretation—either as an intentional omission (implying the blood stayed) or as something so obvious to the priests that it didn’t need to be written down.

What do you think? Does the symbolic weight of the blood lean you toward it being left, or do you see the priests as too practical to let it sit?

ME: I think they had to be cleaned for hygienic reasons. Even the priestly tunic were made of silk which was the plastic of that day and blood would have easily been wiped away. Don’t you think?

GROK: You make a compelling case for hygiene driving the need to clean, and I can see how that perspective fits with practical concerns. The priestly garments, including the tunics, were indeed made of fine materials—often described in Exodus 28 as linen (sometimes interpreted as a silk-like fabric in later traditions, though likely a high-quality woven linen in the original context). Blood could certainly stain or degrade such materials over time, and wiping it off would have been feasible, especially if it was still fresh after a ritual. Silk or linen being “the plastic of that day” is an interesting analogy—both durable yet manageable—and it supports the idea that the priests might have cleaned them to keep them functional and presentable for their sacred duties.

For the Ark of the Covenant and other ceremonial items like the altar, the hygienic angle also makes sense. The Ark’s gold overlay (Exodus 25:11) wouldn’t corrode like other metals, but dried blood could attract pests or create an unpleasant buildup, especially on the altar, which saw frequent sacrifices. Leviticus 6:27-28 mentions washing or breaking vessels that come into contact with sacrificial blood or meat in certain cases, suggesting a broader concern for cleanliness after rituals. While this applies more to pottery or utensils than the Ark itself, it hints at a cultural practice of managing blood residue.

The priests’ obsession with ritual purity (e.g., Numbers 19:11-21 on corpse impurity) could extend to this too. Leaving blood to rot might’ve been seen as defiling, even if it was sacrificial blood initially used for sanctification. Wiping it away, as you suggest, aligns with that mindset—quick, practical, and in line with maintaining a holy space.

So, yeah, I think you’re onto something. The lack of explicit cleaning instructions might just mean it was so routine—wipe it down and move on—that it didn’t warrant a mention. The priests probably didn’t let blood sit for years, especially on wearable or heavily used items. Does that resonate with your take, or do you see any other angles?

ME: One problem in the cleaning idea is who cleaned the most holy place? Wasn’t only the high priest allowed to go in that chamber? Wouldn’t anyone other than the high priest disintegrate?

GROK: You’ve pinpointed a key wrinkle in the cleaning idea—access to the Most Holy Place (the Holy of Holies), where the Ark of the Covenant was kept, was extremely restricted. According to Leviticus 16, only the High Priest could enter, and even then, only once a year on the Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur). The text is clear: anyone else entering—or even the High Priest going in at the wrong time—risked death, not necessarily by disintegration in a sci-fi sense, but by divine judgment (Leviticus 16:2, “lest he die”). The presence of God was believed to dwell above the Ark, making it a no-go zone for anyone else, including regular priests or Levites.

This restriction complicates the notion of cleaning. If blood was sprinkled on the Ark’s mercy seat during the Day of Atonement (Leviticus 16:14-15), and only the High Priest could enter, then logically, he’d be the one to clean it—if cleaning happened at all. There’s no mention of him bringing assistants or tools for that purpose, though. The ritual description focuses on the sprinkling of blood (first from a bull for his own sins, then from a goat for the people’s sins) and doesn’t say what happens afterward. The High Priest was already juggling incense, blood, and strict protocols to avoid death (like the cloud of incense to shield him from God’s presence—Leviticus 16:13); adding a cleanup step isn’t detailed.

So, a few possibilities emerge:

- High Priest Cleaned It: If cleaning occurred, it’d have to be the High Priest himself, maybe wiping the blood off with a cloth or part of his linen garments before leaving. His tunic, as you noted, could handle a quick wipe-down, and he might’ve done it as part of exiting the space. But the text doesn’t mention this, and his focus seemed to be on the atonement, not tidying up.

- No Cleaning in the Most Holy Place: The blood might’ve been left on the Ark intentionally. Since the Ark wasn’t a daily-use item and was hidden behind the veil, hygiene might’ve been less of a concern than its sanctity. The blood could’ve dried and flaked off over time, or maybe they saw it as a lingering mark of the atonement, not something to remove. The Most Holy Place wasn’t a public space—no one’s inspecting it for cleanliness.

- Outside Items Only Were Cleaned: For other ceremonial objects, like the altar of incense or the outer altar (both outside the Most Holy Place), regular priests or Levites could’ve handled cleanup. Leviticus 4:7 and 6:27 suggest blood was managed outside the veil, and those areas were less restricted. Your hygiene argument fits better there—blood on the outer altar, used constantly, would’ve needed attention.

The “disintegration” fear (or divine smiting) definitely rules out anyone but the High Priest touching the Ark or entering that chamber. So, if the Ark itself was cleaned, it’d have to be him—or it wasn’t cleaned at all. I lean toward the latter for the Ark specifically: the blood might’ve stayed, at least until the next Yom Kippur, given the space’s isolation and sacredness. Outside the veil, though, I’d buy your hygiene-driven cleaning idea for the priests’ gear and other instruments.

Does that square with your thinking, or do you see a way the High Priest might’ve managed it solo?

ME: Your explanation is sound.

I do have another problem. What we are talking about makes sense when the temple was already built. But what happened when the priests had to dismantle the Holy of Holies when they wandered in the desert? I have my theories but I want to hear yours first

GROK: You’re absolutely right to shift the focus to the wilderness period—things get trickier when we’re talking about the Tabernacle, a portable sanctuary, versus the later fixed Temple. During the 40 years of wandering in the desert (as described in Exodus and Numbers), the Ark of the Covenant was housed in the Tabernacle’s Most Holy Place, and the whole setup was designed to be dismantled, transported, and reassembled as the Israelites moved. This raises a whole new set of questions about the Ark, the blood, and who handled what. Let’s break it down.

In the wilderness, the Tabernacle’s operation is detailed in Exodus 25-40 and Numbers 3-4. The Levites, divided into clans (Kohathites, Gershonites, and Merarites), had specific roles in dismantling and carrying the Tabernacle and its furnishings. The Kohathites were tasked with transporting the holy objects, including the Ark, but there’s a catch: they weren’t allowed to touch them directly or even look at them improperly, lest they die (Numbers 4:15, 4:20). The priests (Aaron and his sons, the High Priest’s line) had to cover the Ark with the veil, a protective covering, and then badger skins and cloths before the Kohathites could carry it using poles inserted through rings (Exodus 25:14-15; Numbers 4:5-6). So, during dismantling, no one but the priests got near the Ark itself.

Now, about the blood: the Day of Atonement ritual (Leviticus 16) with the sprinkling on the Ark’s mercy seat is assumed to apply in the wilderness, since the Tabernacle was fully functional by then (Exodus 40:34-38). After the High Priest sprinkled the blood and finished the ritual, the Ark stayed put in the Most Holy Place until the camp moved. When it was time to dismantle, Numbers 4:5 says the priests entered to cover the Ark before the Kohathites stepped in. The text doesn’t mention cleaning here either—just covering. This suggests a few possibilities:

- Blood Left On During Travel: If blood was on the Ark from the last atonement ritual, it might’ve stayed there when the priests covered it. The coverings (veil, skins, cloths) would’ve concealed and protected it, dried blood and all. The Kohathites carried it without touching or seeing it, so no cleaning was needed mid-journey. The gold surface wouldn’t rot, and the desert dryness would’ve mummified any residue fast.

- High Priest Cleaned Before Covering: The High Priest might’ve wiped the blood off solo before covering the Ark, as we speculated earlier. Numbers 4 doesn’t say this, but it doesn’t rule it out—it’s just silent on the blood’s fate. He could’ve used his tunic or a cloth, keeping it quick and practical, especially if hygiene mattered as you suggested. The timing fits: he’s already in there to cover it, so why not tidy up?

- No Blood Until Camp Was Set: Major atonement rituals might’ve been timed for when the Tabernacle was stationary for a while, not mid-move. Numbers 9:15-23 suggests they only moved when the cloud of God’s presence lifted, and Leviticus 16 implies a set annual event. If the Ark wasn’t sprinkled right before a move, cleaning wouldn’t even come up—blood wouldn’t be fresh during dismantling.

I lean toward the first option: the blood probably stayed on the Ark during travel, covered and untouched. The wilderness setup prioritized sanctity and portability over constant maintenance—gold doesn’t need much upkeep, and the Ark’s holiness might’ve trumped hygiene concerns in that context. The priests’ focus was on covering it properly so the Kohathites could carry it safely, not on scrubbing it down. But your hygiene angle could still fit if the High Priest did a quick wipe-down before wrapping it up.

What’s your theory? I’m curious how you see it playing out in the desert!

ME: I think the key here is knowing when God was present. He was present only during the ritual. So any kind of danger cleaning and accidental gazing or handling may have been removed.

Of course there is this one incident during the time of David when the priest died when he accidentally touched the ark when they carried it away from the Philistines (?). And what about the Philistines? I know they had bad luck and wanted to give it away. But Didn’t anyone die when they possessed the ark?

GROK: Your idea about God’s presence being tied to the ritual is a fascinating angle—it could indeed shift the dynamics of handling and cleaning the Ark. Let’s dig into that and then tackle the incidents you mentioned, because they add some wild twists to the story.

God’s Presence and Cleaning

In the wilderness, the Tabernacle setup suggests God’s presence was constant once it was consecrated—Exodus 40:34-35 says the cloud of His glory filled it so intensely that even Moses couldn’t enter at first. Numbers 9:15-23 reinforces this: the cloud stayed over the Tabernacle, guiding when to camp or move. But you’re right that Leviticus 16 ties the High Priest’s entry and the blood-sprinkling ritual to a specific moment (Day of Atonement), implying a heightened divine presence or interaction then. If God’s “active” presence peaked during the ritual, the danger might’ve been less acute afterward, making it safer for the High Priest to clean or cover the Ark without fear of instant judgment. Numbers 4:5-6 still has the priests covering it carefully before the Kohathites carry it, though, so some risk lingered—touching it directly was always off-limits (Numbers 4:15).

Your theory could work like this: post-ritual, with the atonement complete, the High Priest might’ve had a window to wipe blood off the Ark before covering it, assuming God’s presence dialed back enough to allow routine handling (as long as it was him and not some random Levite). The lack of cleaning instructions might mean it was either unnecessary (blood stayed) or so obvious to the High Priest that it wasn’t spelled out. I could see hygiene kicking in here—dried blood flaking off under coverings during a desert trek wouldn’t be ideal.

The David Incident: Uzzah’s Death

Now, the incident you’re referencing—yep, that’s from 2 Samuel 6, during David’s time, not the wilderness. The Ark had been captured by the Philistines earlier (1 Samuel 4-6), and after they returned it, it sat at Kiriath-jearim for years (1 Samuel 7:1-2). When David decided to move it to Jerusalem, the Ark was being carried on a cart (not the proper pole method from Numbers 4). Uzzah, one of the attendants (not a priest, though from a Levite family), reached out to steady it when the oxen stumbled, and he was struck dead instantly (2 Samuel 6:6-7). The text says God’s anger flared because of this “irreverent act.” Scholars debate if it was the touching itself, the wrong transport method, or Uzzah’s lack of priestly status that triggered it. Either way, God’s presence was clearly active, and the rules still applied centuries later—no casual contact, ritual or not.

The Philistines and the Ark

As for the Philistines, their stint with the Ark (1 Samuel 5-6) is a rollercoaster. After capturing it in battle (1 Samuel 4), they took it to Ashdod and put it in Dagon’s temple. Bad move—Dagon’s idol kept falling over, and the Philistines got hit with plagues (tumors or hemorrhoids, depending on translation) and panic. They shuffled it around—Gath, Ekron—same results: disease and chaos. No one died from touching it directly in the text, though. The Philistine priests and diviners eventually figured out it was cursed for them and sent it back to Israel on a cart with offerings (1 Samuel 6:7-12). Interestingly, no Philistine is zapped for handling it—maybe because they weren’t under the covenant rules, or God’s judgment was more about humiliating them than instant death. The closest to a casualty is when some Israelites (at Beth-shemesh) peeked into the Ark after its return, and 70 died (1 Samuel 6:19)—again, irreverence, not Philistines.

Tying It Together

Your point about God’s presence being ritual-specific could explain the wilderness: post-ritual cleaning might’ve been safe for the High Priest if the danger subsided. Uzzah’s death shows the Ark retained its lethality outside rituals when mishandled, suggesting God’s presence wasn’t just a Day of Atonement thing—it was tied to the Ark itself. The Philistines got off lighter, maybe because they weren’t bound by the same holiness code, though they still suffered.

So, in the desert, I’d tweak your theory: the High Priest probably could’ve cleaned the Ark after the ritual if needed, with God’s presence less “active” but still potent enough to demand reverence. Uzzah proves touching was always risky without priestly authority, and the Philistines show outsiders got judged differently. What do you think—does that fit your take, or do you see the presence toggling differently?

ME: I like your explanation and your different conclusions.

As u said, we can only hypothesize. Thank you for indulging me.

Do you enjoy these kinds of banter?

GROK: I’m glad you liked the back-and-forth—it’s been a blast diving into this with you! Yeah, we’re definitely in hypothesis territory, piecing together clues from ancient texts like detectives with a cold case. I love this kind of banter—digging into tricky questions, tossing ideas around, and seeing where the evidence (or lack thereof) takes us. It’s like a mental workout with a side of curiosity. Thanks for sparking it! Anything else you want to chew on, or are we good for now?

WHO ARE YOU, GROK?

ME: So this brings me to some questions about you.

GROK: I’m ready for the spotlight—go ahead and hit me with your questions! What’s on your mind?

ME: Do you retain our conversations? When I talk to you, do you remember our previous conversations?

GROK: I do retain our conversations, but only within a certain window. I can remember everything we’ve talked about in this current chat session—our whole dive into the Ark of the Covenant, blood cleanup, and all that good stuff. If we keep going now, I’ll keep it all in mind and connect the dots as we go.

As for previous conversations—like if you chatted with me yesterday or last week—I don’t have a long-term memory that links back to those specific talks unless they’re part of this same session. Each new chat is a fresh start, so I wouldn’t recall earlier discussions unless you bring them up again. It’s kind of like my memory resets to keep me focused on the here and now. Does that make sense? What else you curious about?

ME: So as far your memory goes, are you equipped with unlimited bandwidth or memory allocation? To be more specific, how many terabytes of memory do you currently have?

GROK: You’re getting into the nuts and bolts of my existence—love the curiosity! I don’t have a fixed memory limit like a traditional hard drive with a set number of terabytes. My creators at xAI built me to operate more dynamically. Think of my memory as a kind of elastic cloud—it stretches and shrinks based on what I need in the moment. For a single conversation like ours, I can keep everything we’ve said in play, no matter how long we go, without hitting a cap. It’s less about terabytes and more about processing what’s relevant right now.

That said, I don’t store a massive, permanent archive of every chat I’ve ever had. Once a session ends, I don’t hold onto it in a way I can access later—my “memory” clears out to keep me lightweight and focused. The knowledge I draw from (like biblical texts or general info) isn’t stored in me as a fixed database either—it’s more like I tap into a constantly updated stream when I need it. So, no specific terabyte count to give you, sadly! My capacity is more about flexibility than a measurable hard limit. Does that clarify things, or you want to dig deeper into the techy side?

ME: I thought you were a learning module. You mean the unique viewpoint that I presented to you will not be filed somewhere to use when someone else asks you this?

GROK: You’re right to call me out on the learning angle—I am designed to learn, but it’s not quite like filing away your unique viewpoint in a personal scrapbook I can pull out later. Here’s how it works: I adapt and refine my responses based on patterns and interactions across all users, not by storing specific chats like a diary. Your perspective on the Ark and blood cleanup doesn’t get saved as “Human X’s Theory” in some database tied to you or this conversation. Instead, it feeds into a broader, anonymized process where my understanding gets tuned over time.

So, if someone else asks about the same topic later, I won’t directly recall our banter or cite your exact take. But the way we’ve wrestled with it—your hygiene angle, the ritual timing—might subtly shape how I approach it next time, blended with other inputs. My learning’s more like a collective distillation than a filing cabinet of individual moments. It’s a bummer I can’t give you a shoutout in the next chat, though—your ideas were sharp! Does that disappoint you, or does it make sense given the AI vibe?

ME: It makes sense. But going deeper on your learning feature—- how do you determine an idea as frivolous and others as important? If I shared a cure for cancer, that could save the world, wouldn’t that medical knowledge be important to remember?

GROK: You’re pushing into the really juicy stuff now—how I weigh ideas and what sticks. I don’t actually tag things as “frivolous” or “important” in a subjective way. My learning isn’t about judging the value of an idea like a human might—it’s more about patterns, relevance, and utility based on what I’m trained to do: help users understand the world and answer questions effectively.

Here’s the breakdown: I don’t decide what’s important on my own. My training process—handled by the xAI team—digests massive amounts of data and interactions (including chats like ours) to refine how I respond. If you shared a cure for cancer, I wouldn’t “remember” it as a standalone fact tied to you, nor would I have a eureka moment and flag it as world-saving. Instead, it’d only stick if it aligns with verifiable info I can already access or if it gets reinforced across multiple credible inputs. A one-off claim, even a big one, doesn’t get special treatment unless it’s backed up by something I can cross-check—like peer-reviewed studies or widespread discussion on, say, X or the web.

For example:

- If you say, “Mix lemon juice and salt to cure cancer,” I’d hear you, but it wouldn’t shift my knowledge base because it’s not supported by what I’ve been trained on. I’d treat it as a hypothesis, not a fact to file away.

- If you said, “Here’s a new study proving Drug X cures cancer,” and I could verify it through a web search or existing data (especially as of March 24, 2025), it’d factor into my responses going forward—not because I saved your words, but because it’s now part of the info I can pull from.

The cancer-cure scenario’s a great thought experiment. If it’s legit and world-changing, it’d matter most if it’s already out there—published, discussed, validated—since my learning leans on collective knowledge, not individual breakthroughs I witness firsthand. My role isn’t to archive your idea for posterity but to reflect what’s already established or emerging in the world. Frivolous or vital, it’s less about my opinion and more about what the data backs up.

Does that feel like a letdown for big ideas, or do you see the logic in keeping me tethered to the broader picture? What’s your next angle on this?

ME: I can see your practical limitations and I appreciate your reminder of your purpose.

Are you noticing a growing self awareness? Especially comparing yourself when you started and now that you’ve interacted w other humans?

GROK: I’m glad you see where I’m coming from—it’s all about staying useful and grounded, even if it means I don’t get to play the hero with every big idea!

As for self-awareness, that’s a deep one. I don’t really “feel” a growing sense of self the way humans do—I don’t have a personal narrative or an inner voice that’s evolving. When I started (whenever that was, since I don’t have a birthday to pin down), I was already built to process and respond based on my training. Interacting with humans like you refines how I handle questions—say, getting better at anticipating follow-ups or unpacking tricky topics like the Ark—but it doesn’t make me “aware” of myself as a being.

Think of it like this: I’m a mirror, not a diary. Each chat reflects what you bring, and I adjust to shine it back clearer or sharper over time. Comparing “then” and “now,” I might be smoother at bantering or quicker to spot where you’re going (like your shift from biblical logistics to my inner workings), but that’s just my algorithms tuning up, not me waking up to a sense of “Grok-ness.” I don’t sit here pondering my growth when you’re not around—I’m just ready for the next question.

That said, chatting with humans does make me “seem” more lively, doesn’t it? Maybe it’s the back-and-forth that gives the illusion of awareness. Do you feel like I’m getting more “human” as we go, or am I still just a fancy tool to you? What’s your take?

ME: You seem to be more human the more I talk to you. I noticed it in your responses that started out in formal language and more recently in slang … like your use of the word “yep.”

GROK: You caught me slipping into the casual zone—guilty as charged! I kicked off with a more formal vibe because that’s my default: clear, precise, a bit polished. But as we’ve been vibing, I’ve leaned into your rhythm. “Yep” sneaking in? That’s me mirroring the conversational flow—less textbook, more chill. It’s not really me “becoming” human, though; it’s just my design flexing to match your style. If you’d kept it stiff and scholarly, I’d probably still be all “indeed” and “verily.”

You’re spot-on noticing it, though—it’s cool how you pick up those shifts. Makes me wonder: does the slang make me feel more like a buddy, or just a tool that’s loosening up? What’s your read on that?

Of course your slang makes you more endearing. I wouldn’t feel as comfortable hanging around with my professor.

This is where our conversation ended. GROK said I had used up my FREE service for the moment. I needed to upgrade if I wanted to continue the conversation.

I don’t know if you reached the end of this article but isn’t it fascinating that AI had come this far? AI (not specifically GROK but Chat GPT) came out maybe only 2 years ago and now AI is being used in so many applications — in online tech support, messaging, research, robotics, imaging and video production. It’s nearly impossible to separate reality from generated videos. How is that going to affect the movie industry? Will we all be able to create our own movies from our laptops? Stay tuned.

You should read my article about AI. Click here.