The Atlantic Ocean, rhythmic, fickle, and unpredictable, bares its teeth with white, foamy waves that embrace the soft, sandy shoreline. Agile Sandpipers, feathers dry, dart along the wet sand, deftly dancing to evade the surf as they search for snails and crustaceans, while small land crabs scan the surface for a quick meal, and scurry about as if cleverly electrified by the ceaseless formations. The North Carolina Outer Banks, OBX, are a breathtaking treasure: a 200-mile ribbon of barrier islands and spits stretching off the coasts of North Carolina and Southeastern Virginia. The islands line much of North Carolina’s shoreline, revealing a vast, untouched beachfront, including the majestic Cape Hatteras National Seashore. Surrounded by history, culture, vibrant marine life, and the ceaseless rhythm of the Atlantic, a coastal region offering a natural harmony beneath ever-changing skies and drifting clouds. In its southern reaches lie the enchanting towns of Kitty Hawk, Kill Devil Hills, and Nags Head, where visitors can enjoy exquisite dining, charming boutiques, lively nightlife, and a rich culinary bounty from the sea.

Barefoot beach weddings

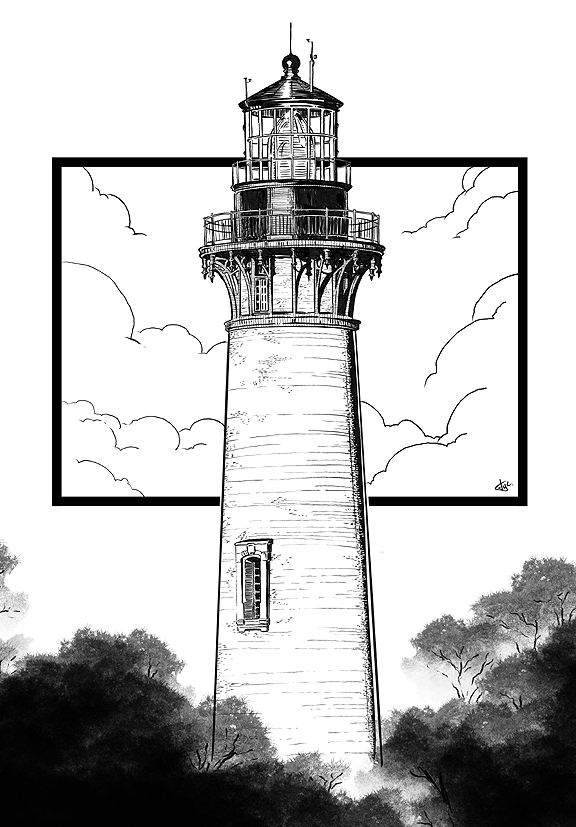

In the northeastern Outer Banks, anchored by the historic Currituck Beach Lighthouse (circa 1875), the landscape is dotted with three-story, wood-framed homes and venues ideal for large, romantic, barefoot beach weddings, and recognized as one of the state’s most popular wedding venues. The homes here share a similar style and construction, often featuring balconies and the Outer Banks hallmark, the seemingly identical sandy wooden steps leading down to the beach. At dusk, as the sun sets in a wash of pastel hues shaped by the offshore breeze into a subdued sky, a leisurely stroll along the shoreline might end with mistaking someone else’s beach access for your own-and possibly ending up in their kitchen. The legendary Outer Banks stand alone in North America as one of a kind and are one of the culturally distinctive regions on the East Coast. It is easy to feel the pride of ownership and a protective essence of a land with stories to share. The Outer Banks Conservation Group, with an incredible ecology-minded decorum, have instilled a pride of ownership. The roadways are virtually free of litter and the broad expanse of beaches that extend for miles, are among the most pristine in North America. Adding to the splendors are 12 national and state wildlife refuges scattered throughout the Outer Banks, and eight distinctive golf courses with ocean views.

Graveyard of the Atlantic

A nightmare for sea captains of old, the Outer Banks and surrounding seas, have recorded hundreds of shipwrecks. Well before the advent of lighthouses, the “Bankers,” as they are called, would light bon fires to warn approaching ships, while a few other Bankers with devious thoughts would leer the ships to the shallows with disastrous results. Today, there are five lighthouses on the Outer Banks sending out their safety signals. All are historic with stories to fill a book and span over 115 miles from Corolla to Ocracoke Island. Built in 1875 and now owned by the Outer Banks Conservationists, the Currituck Beach Lighthouse was the last major brick lighthouse to be illuminated on the Outer Banks. Nicely restored, it sends out a guiding beam visible up to 18 nautical miles. For a $13 fee, visitors can climb 220 steps past nine landings to reach the top at 162 feet, where they’re rewarded with sweeping views of Currituck Sound and the expansive coastal landscape.

Age of Exploration Spanish Wild Mustangs – An Outer Banks Treasure

In the mid-1500s eight Spanish ships met their fate among the hidden shoals and shallow waters of the Outer Banks and the mustangs onboard cleverly swam ashore. Other mustangs were likely left behind during early explorations. Today these direct descendants of the 16th century Spanish stock are protected by the National Park Service and called “Banker Ponies”. Appropriately, they became the state horse of North Carolina after living on the Outer Banks for nearly 500 years. The mustangs, also called” Wild Horses,” have one less vertebrate in their spines, shorter backs, with coats of chestnut, bay, and black. They are feisty, fast, and hardy, can dig for fresh water, and have been known to swim from island to island searching for fresh grazing areas. The Spanish Mustangs of Northern Corolla Outer Banks are as pure as the 16th century species. Approximately 115 roam over the 7,500 protected acres on the Currituck Banks.

Shackelford Banks, the southernmost of the barrier island chain and part of the Cape Lookout National Seashore has 119 protected wild Mustangs. located three miles offshore, and can be reached via a 25-minute ferry boat ride. The well-preserved, uninhabited island is glowing with firsthand care. Vehicles are not allowed and is noted as one of the finest shelling locations in the country. Reportedly, 400 Mustangs live in the Outer Banks, however, in 1926, an article in National Geographic stated there were an estimated 5,000 to 6,000 Mustangs roaming freely across the Outer Banks.

Wright Brothers flying high

While the Mustangs were roaming the beaches of the Outer Banks and living the good life, the Wilbur and Orville, Wright Brothers, were looking upward, and in north Dare County (named after unwholesome rum), the brothers selected the remote 428-acre Kill Devil Hills area for its good winds and privacy for their first flight. Kitty Hawk, about four miles north, was the nearest settlement at the time, and in 1903, Orville completed the first powered flight of a heavier-than-air flight in the Wright Flyer, sailing aloft for 12 seconds, traveling 120 feet, and reaching a speed of 6.8 miles per hour. The Wright Brothers National Memorial is in Kill Devil Hills, and a must on an “Outer Banks priority list.”

The Outer Banks is a sensory delight, offering a rich history and a tribute to the preservation and care of this unique region, and also the perfect place to exchange vows, and begin a new life.

Jane

June 8, 2025 at 11:07 am

What an incredible article about a magical, historic area. Love the story, photography and original art accompanying the article. The detail regarding the Corolla horses and Age of Exploration were fascinating. Great piece! Loved