|

|

|

|

|

In the Footsteps of Hippocrates

By Eric Anderson, MD Photography by author and Nancy Allen Anderson, RN

|

|

The small airplane for the Greek island of Kos fills up rapidly at the Athens airport.

The passengers sure comprise an eclectic bunch: Bronzed blondes jabbering in German, British tourists sweating in their heavy tweeds, young Greek couples incessantly smoking and blowing their fumes carefree into each other’s eyes, island families returning after a day in the city, and exhausted babies crying in their mother’s arms. Elderly men awkwardly feeling their slow way down the aircraft corridor carrying --- like waiters bearing trays --- crumpled cardboard boxes bound in twine, or dragging plastic bags incongruously labeled “Camel Cigarettes” or “Dewar’s Whiskey,” stuffed with newspapers, rugs, boots and jackets. Thin stooped women --- in the mournful black they’ll wear for forty years of widowhood. A Greek priest, as always bearded, pausing indulgently on his way to his seat to permit a woman kiss his hand. Two Spaniards sweeping down the passage, inches apart yet shouting incoherently at each other. A tourist, again German, laden with the most expensive photographic equipment that was ever sold forty years ago --- all gleaming, stainless steel and heavy on his neck. And, me, a wide-eyed North American physician and my wife making a pilgrimage as devoutly as any character in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales --- to where medicine began twenty four centuries ago in the land of Hippocrates, the island of Kos.

Today things are different. There were only two flights a day until 1990 but tourism discovered the island then --- and now Boeing 737s and other jets fly 4 to 5 times a day. The local population has remained essentially the same. It was for example 19,850 in 1981 and 19,412 in 2001 but the change in the number of visitors is striking. Kos had, in 1985, an impressive enough 214,836 visitors but in 1995 it had 532, 341 and in 2005 606,608 noisy, exuberant tourists came. Paralleling this was the increase in the number of hotel beds: from 14,500 in 1985 to 45,100 in 2000 and now 65,000 in 2008.

Presently from mid June to early September, much of the island is a madhouse of young, often drunk, European tourists on organized all-inclusive tours. Unattractive modern buildings impact the Italian and Greek architecture and the east coast of the island in particular is crowded with concrete. Kos has been “discovered” by group travel.

Still Greece to most of us is a mystical place where the greatest civilization in history began and democracy first flowered, and to doctors where the greatest physician of all time was born, lived and practiced his craft on this remote island. Kos (sometimes spelled Cos) lies so far east in the Dodecanese chain its shores are only four miles from the mainland of Turkey. It’s the Greek island still least visited by North Americans. I went in the off-season to savor what it offered. And what it offered was the land where time still moved to ancient rhythms. We sit in a taverna in what used to be the little town of Kardamena, 18 miles southwest of the capital. Our lunch is the typical “peasant salad” of tomatoes, olives, cucumbers, and onions with huge chunks of feta cheese on top and honey and yogurt on the side. Even for spring, it is a hot, sleepy day and no one is in a hurry --- especially the waiter. We mention this to a Greek companion, who responds with the remark still heard even today, maybe especially today, all over Europe: “Americans hurry too much.” He points out the owner of the taverna, a burly, bluff man sitting with his male friends around a long table in a corner. They are all clutching their ouzo, telling stories and having a great time. When I look around the restaurant I notice there are no females dining this evening: “Our women don’t like to go out!” explains our chauvinistic Greek, contentedly puffing on his cigar. My wife, by Greek standards a feminist, gives him a look that would knock Rocky Marciano off his feet. “I was in this restaurant last week,” our companion goes on, “when an American tourist signaled he wanted his bill. He couldn’t get the owner’s attention. Finally he went over and said he wanted to pay. The owner replied he’d come to the man’s table in half an hour --- he was with friends. The American got angry and said he’d leave without paying if he couldn’t have his bill immediately. The owner said, ‘That’s okay. Go.’ “The American flung some money on the table and stormed out. He didn’t understand: Sometimes money isn’t important.”

Now in the 21st Century it is important. To a degree it consumes the island. Visitors who make the mistake of coming in high season find even the secluded beaches on the west coast fill up fast when water taxis from Kos Town discharge its revelers. Even the inland villages like Zia in the Asfendiou district on the slopes of Mount Dikaion can become busy when visitors show up to enjoy the magnificent sunse --- and buy tourist trinkets in the now prevalent stalls. Money has become important. I think back on this when I recall my first shopping excursion on Kos in the 1980s.

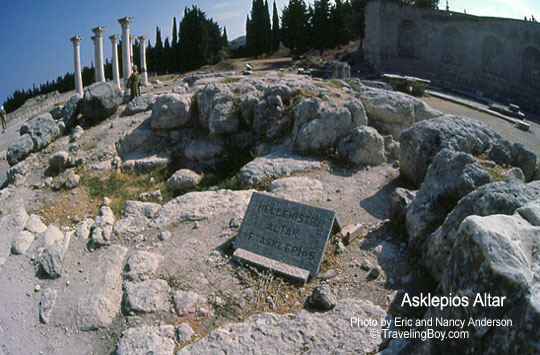

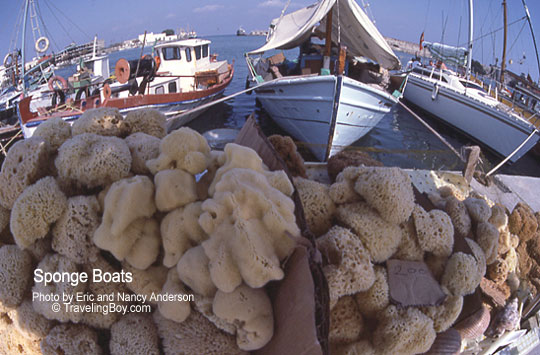

At the harbor an old fisherman has laid out sponges harvested fresh from the sea. Usually Greeks enjoy haggling --- and, of course, originally being Scottish --- I like a bargain, too. He has two qualities of sponges with brown cardboard signs showing the prices of $1 and $2, expressed oddly enough in US dollars. I pick up a big $2 sponge from the table and say, hopefully, “One dollar?” He slaps my hand --- I hope playfully --- and says, “You bad boy!” I go back to the hotel to show my wife the $2 bargain sponge I’d got for $2. The next day, I drive two-and-a-half miles out of Kos, past chickens and pigs and goats, past honey-colored walls spilling over with bougainvillea and gardens cluttered with olive trees and oleanders to the most famous architectural ruins in medical history. When Hippocrates was born on Kos in 460 BC, the prosperous island was home to 160,000 people. Today, the population is one-fifth that number. Thanks to tourism, however, local residents are regaining some of their affluence. Astypalaia, the capital in the fifth century BC, lay on the west side of the 28-mile-long island, distant from the eastern sea routes --- and the pirates who plied them. This gives some credibility to the theory that Hippocrates taught his students on the west coast of Kos, nowhere near the present capital. Indeed, according to some historians, the father of medicine never entered the temple of healing, the Asklepieion. Maybe. But when the settlements in the western part of the island were destroyed by an earthquake and a subsequent Spartan invasion in 411 BC, the people moved to the present location of town, to be close to a friendly populace and the Asklepieion itself. Some writers, describing a fire there, declared Hippocrates tried to save “manuscripts and tables of the temple” and was severely burned, nearly losing his life.

This ancient center of healing, the Asklepieion, was spread across wooded groves on the lower slopes of Mount Oromedon. That the grove was sacred in earlier times adds to the belief that Hippocrates practiced here, even though his teachings and writings were the antithesis of the “incubation” ceremonies, miracle cures, and other religious rituals of ancient Greece’s temple priests. The area is laid out in three terraces. The view from the upper level carries the eye over tall cypress trees to the green fields and cobbled streets of Kos, to the harbor and the 14th-century battlements of the Knights of St. John and --- beyond the turquoise sea --- to the coastline of Turkey itself. In contrast to many archaeological sites, this one is easy to understand. The lower terrace was the entrance and arena for special events. It contained health spas, bathhouses, and fountains spouting water from nearby springs. The water of one fountain was rich in sulfur, a laxative. Says a local author, Christa Mee, “Whatever effect the water was intended to produce upon invalids, it’s perhaps no coincidence a sumptuous latrine was constructed in the vicinity.” The middle terrace, 30 steps up, contains the foundation of the altar of Asklepios. Built between 350 and 330 BC, it is the earliest symbolic structure left on the hillside. On the right, the west side of the altar, rises up the Temple of Asklepios, constructed in the third century BC to house gifts the sick brought their priest-physicians. To the east lies another temple constructed by the Romans and dedicated to Apollo. Sixty more marble steps bring visitors to the foundation of the huge temple of the upper terrace, built in the second century BC with 104 Doric columns around its 340-foot perimeter. Little of value remains in the Asklepieion, however. The Knights of St. John used parts of it for fortification against the Ottoman Turks. There are more than 300 centers in the ancient world named for Asklepios but none as famous as this. I stand on the upper terrace, imagining what Hippocrates’ students must have felt sitting at his feet here or, according to legend, sprawling under the great plane tree in the center of town. The tree still exists propped up by strong supports. I gaze at it but the cynic in me says, surely no tree could be that old!

Beyond the Roman courtyard stands a statue from the fourth century BC --- identified by Italian architects in 1933 as Hippocrates himself. It surfaced when an earthquake exposed what had been an arena, the Odeon. The statue dominates an apse at the end of a hallway. The sun streaming in through the overhead window bathes it in a strange, deep-green light as the figure stares into the distance. I drop down on to the floor and stare back. A museum guide, an old bent-over man, watches me cautiously. He frowns and points to the sign “No Photography.” I touch the camera on my lap and look at him beseechingly. He shakes his head. I try to show how entranced I am with his statue, his museum, his island, his country. He shakes his head. I hold my hand over my heart. “Doctor,” I say and look wistfully at the statue. He glances at his watch. “OK,” he says, “Yes, OK.” Wondering if this could indeed be Hippocrates and overwhelmed by the thought --- I lift my camera. At, for me, that mystical moment I feel somehow my journey is validated and my nostalgia complete.

Demetra Mitropoulou, a spokesperson in the Greek National Tourist Organization in New York City tells me of a recent best-seller in Greece that talks about health and alternative medicine, certainly popular subjects today. Says Mitropoulou, “The book is as current and significant today as it ever was. Rewritten in a contemporary voice, the book is called APANTA: All About Medicine. Its author is a Greek physician named Hippocrates.” |

I liked the article. As I read it, I was wondering how you as a physician were influenced by Hippocrates. What influence did this historical figure have on the practice of medicine beyond the obvious 'oath.' Why is Hippocrates considered to be such a paragon of medicine? DWA - San Pedro, CA * * *

Thank you for writing to Travelingboy.com. Hippocrates is revered because he believed his duty was to the individual patient, not to the community at large. This is a very important premise. The Romans, whose empire followed that of the Greeks, achieved much in health matters by emphasizing clean drinking water and personal hygiene, and created great national works like aquaducts and public baths but wealthy Romans apparently preferred Greek doctors as their personal physicians. Hippocrates is also respected because he brought intellectual thought to diagnosis. He taught his students to use their five senses in assessing patients and was openly critical of the junk science of his day as practiced by the priest-physicians who preyed on the fear and ignorance of the ill persons who came to them. It is true that not all medical chools today require graduating doctors to take the Hippocratic Oath but most conscientious physicians base their lifetime commitment to the practice of medicine on the life and teachings of that one man. Or so I think. Perhaps if we knew more about our heroes they would seem less heroic. But in Hippocrates' case he did leave a record of his thoughts and some of his principles are today as strong as ever. Thank you for writing, it is appreciated. Eric Anderson

|

This site is designed and maintained by WYNK Marketing. Send all technical issues to: support@wynkmarketing.com

|

But

is this temple, the Asklepieion, unearthed in 1902, the same one

honored by Hippocrates? Many archaeologists believe so. That’s

good enough for most physicians who know as they wander in the

Asklepieion they’re walking in the footsteps of Hippocrates

himself.

But

is this temple, the Asklepieion, unearthed in 1902, the same one

honored by Hippocrates? Many archaeologists believe so. That’s

good enough for most physicians who know as they wander in the

Asklepieion they’re walking in the footsteps of Hippocrates

himself. Yet

when I walk into the Greek Archaeological Museum in the town center

I become a believer again. I nearly step on one of its treasures,

a mosaic floor transferred from Casa Romana, a Roman villa in

the ancient part of town that is in the process of being renovated.

The mosaic shows Asklepios, the god of healing, arriving on the

shores of Kos and being welcomed by an islander and by Hippocrates

himself. Created in the third century AD, about 600 years after

the death of Hippocrates, it remains one of the few illustrations

of medicine’s founder.

Yet

when I walk into the Greek Archaeological Museum in the town center

I become a believer again. I nearly step on one of its treasures,

a mosaic floor transferred from Casa Romana, a Roman villa in

the ancient part of town that is in the process of being renovated.

The mosaic shows Asklepios, the god of healing, arriving on the

shores of Kos and being welcomed by an islander and by Hippocrates

himself. Created in the third century AD, about 600 years after

the death of Hippocrates, it remains one of the few illustrations

of medicine’s founder.