|

|

|

|

|

Monte

Verità:

In the Footsteps of Anarchy Story and Photos by Gary Singh

Through a smattering of oak trees, wild olive plants and earthy foliage in every shade of green, I see Lake Maggiore, far down below, as it fades into the labyrinthine neighborhood of Ascona, Switzerland. Across the sapphire-colored lake, the hills lurch above the horizon like mammoth foreheads. Sailboats lilt on the water, although from my vantage point up here on the hill, they are but white specks.

Nearly a century ago, this hill, Monte Verità, welcomed anarchists, vegans, occultists, nudists and a detoxing Herman Hesse, but today, except for the Italian academics finishing up their biochemistry conference at the Bauhaus hotel and congress facility directly behind me, I am the only one staying here. The birds and the moths don't count since they occupy the place year round.

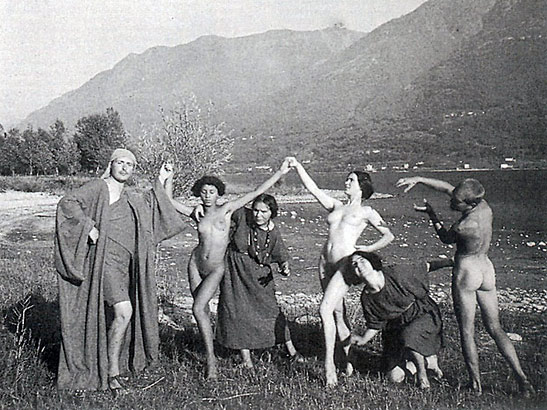

My guide, the white-haired Hetty Rogantini de Beauclair, was born here in 1928. As she leads me around the rest of the property, I become aware that she is the last living connection to the original era of Monte Verità. That era, beginning around 1900, attracted Ida Hoffman and Henry Oedonkoven, who founded the colony. Women took off their corsets. Men wore long hair and beards. Everyone pranced around naked. The colony vowed to return to a simple life, away from what they saw as the horrors of the industrialized world. As anarchists, they strove to simply provide a third alternative, after capitalism and communism. Initially they ate just raw vegetables. Hetty says the only animal allowed was the donkey that carried the water. Naturally, the colony attracted intellectuals, radicals, experimenters and artists of every discipline. Hermann Hesse first arrived around 1907, after which he wrote Demian, his experiment in Jungian self-analysis. The Dadaists Hugo Ball, Hans Arp and Hans Richter soon followed. Lenin came around 1910. A few years later, modern dance pioneer Rudolf von Laban established a "School for Art," attracting a roster of disciples including the dancer Isadora Duncan. Other notables who showed up included the painter Paul Klee, the mystic Rudolf Steiner and the occultist and Grand Master of the Ordo Templi Orientis, Theodor Reuss, who even organized a multidisciplinary conference of his own. Just about every flavor of counterculture throughout the twentieth century can be traced back to Monte Verità.

As Hetty and I traverse the landscape, she keeps complaining that other visitors have left too many pebbles on the trail, making it dangerous to walk on. She keeps kicking the rocks away, out of our path. The de facto caretaker of the property, she does this every twenty minutes or so. As dry leaves and twigs crackle underneath our feet, I get the feeling she knows every square centimeter of the entire topography. At a portion of the property disguised by overhanging trees, she points out relics from 100 years ago: an outdoor shower, bathtub and remains of a tennis court, all of which were originally used by the nudists of Monte Verità. It's 25 degrees Celsius, but I feel like I'm wearing too many layers.

She continues to school me on the history: In 1926, Baron Eduard von der Heydt, a cosmopolitan art collector from Holland with a penchant for Buddhism and other eastern religions, took over the reigns of Monte Verità. Some of the exotic trees he planted still exist on the property. With von der Heydt at the helm, a new era began and he commissioned the German architect Emil Fahrenkamp to construct the Bauhaus-style hotel in 1925. "At that time it was the best hotel in Ascona," Hetty tells me, as we step sideways down an embankment into a large clearing. To the sound of distant seagulls, we stand on a giant lawn Hetty says is common for banquets and events. What used to be a concrete swimming pool 90 years ago has now been converted into an open-air space for meetings, conferences and performances, complete with a stage and lighting trusses.

Normally, one also finds a museum here, housed in the old Casa Anatta building, dating back to 1904, but the structure is currently undergoing renovation. Until the retrofit is complete, the hundreds of artifacts, photos and ephemera are stored down the highway in Bellinzona. Someday they will return.

The space-time continuum easily shatters on Monte Verità. Today, the Bauhaus Hotel still sits atop the hill, presenting elements of the rational and mathematical, juxtaposed against the fluid, imaginative surroundings. ETH Zurich operates the conference facility, which continues to function as a place of research and experimentation. The restaurant offers gastronomical delights with spices from the gardens outside. Eranos meetings, originally launched by Carl Gustav Jung, still continue. There are concerts, plays and even weddings. The hill also claims one of two Peace Poles in Switzerland, steles symbolizing unity and brotherhood that are planted in highly symbolic places throughout the world. The project promotes arts education, friendship and communication, all to cultivate an attitude of inner peace and harmony. Newer components of the complex include a Japanese teahouse and Zen garden, further blurring the boundaries between nature, philosophy, behavior and science--precisely the intentions of the forward-thinking characters that populated this hill 100 years ago. Inside the teahouse, several homemade blends peer at me from underneath a glass case.

At Monte Verità, the spirit of the twentieth century's first counterculture still lingers here. The experience presents a different flavor of historical travel, an unorthodox foray into currents long ignored by conventional twentieth century narratives. Here, I occupy an interstice, simultaneously inside and outside of history.

Related articles: |

|

Your tea adventures are especially interesting because I've always associated tea with British etiquette or a bevy of women wearing dainty victorian costumes and sipping tea with their little pinky sticking out. To see Tea from a man's perspective brings new light in a man's psyche. I've been among the many silent admirers of your writings for a long time here at Traveling Boy. Thanks for your very interesting perspectives about your travels. Keep it up! --- Rodger, B. of Whittier, CA, USA

|

|

| |||

This site is designed and maintained by WYNK Marketing. Send all technical issues to: support@wynkmarketing.com

|