|

|

|

|

|

Amazonia: Not

Your Typical

Tourist Destination Story by Fyllis Hockman Photos by Victor Block

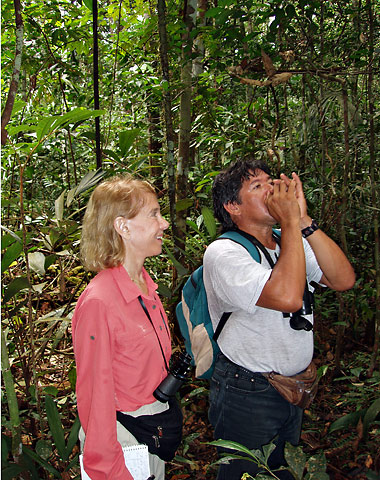

The hike was one of four daily activities during our 8-day adventure exploring Amazonia. Calling the Tucano, a 16-passenger river yacht home, we traveled over 200 miles along the River Negro where the only other waterborne human we saw was the rare fisherman in a dugout canoe. For our daily excursions, we clamored aboard a small power launch which took us hiking, bird-watching, and village hopping, and on night-time outings that dramatized the allure of the river not experienced in any other way. But more on that later.

Souza demanded quiet during our launch rides, using all of his senses to read the forest, listening for the breaking of a branch or a flutter through the trees, sniffing for animal odors, scanning leaves above and below for motion, or the water for ripples… and alerting us at every junction of what he has discovered. On our own, we would have heard, felt and discerned nothing. Souza’s most amazing talent was his ability to identify the multitudes of birds traversing the river and forest, many of whose calls he could replicate precisely. What to us was a dot on a limb was declared a green ibis. Then a snow egret, crane hawk, red-breasted blackbird, jacana, snail kite –- so many I just stopped taking notes. So confidently did he identify the inhabitants, we would have believed: “That’s a green-tongued, red-beaked ibirus with one brown eye and a pimple on his right cheek…”

He could imitate more birds than the most gifted comedian can impersonate movie stars. He carried on such intimate conversations, that halfway through a lengthy discussion with a blackish gray antshrike, I think they became engaged. Then Souza, fickle male that he is, romanced a colorful azure blue-beaked Trogan perched upon a dead branch high in a tree. Birds have a surprising preference for dead tree parts. As one of my travel companions observed, “If you don’t like birds, you might as well take the next flight home.” Back to Machete Man. Our forest walks also were a time for observation, not conversation. On a stop to view teca ants swarming over the bark, Souza wiped his hand across it, proceeding then to rub the ants over his forearms. Instant mosquito repellant –- handy tool in the Amazon. At one point, I looked down and saw a long brown twig draping a log. Souza saw a snake. I looked again and still saw a twig, albeit one that now had an eye. I stepped more gingerly.

We learned of the many medications the forest supplies to the natives; of vines for baskets and brooms; bark for strong rope; plants providing poison for arrows. As we heeded orders to be quiet, the dried leaves below screamed in protest at being trampled, the buzz of the horsefly the most persistent sound. And then there are the leaf cutter ants! A long assembly line of tiny leaves paraded up a hill, as organized as a marching band. A closer look revealed leaf cutter ants to be the burly carriers. Hard to believe something so fragile can carry so large and unwieldy a load as much as half a mile to its colony. Surprised at how much he learned about himself on the trip, Ritesh Beriwal, a 23-year-old worn-out Wall Street trainee, noted: “I didn’t realize how interested I’d be in the little things, like how insects such as the leaf-carrying ants build homes. Before it was just an ant; now it’s an ant with an entire life and work history.” Each day brought new revelations and insight into our surroundings whether on land or water. Our visits to several villages only reinforced that impression. Commonalities among villages: a dance hall where residents party once a month; a soccer field where youth exercise once a day; a school room where students of all grades learn; a clinic that caters to the medical needs of the community, 2-3 requisite churches where parishioners of different persuasions pray -– and a generator. And that’s about it. But the differences are notable as well. I found the contrast particularly interesting between one village of no more than 30 families producing one farm product and a larger “company” town in which thrives an asphalt industry. In the larger village, there is a convenience store, a small café, a bakery. Each hut has its own outhouse and there are several satellite dishes throughout the community. The entire economy of the farm community revolves around manioc –- a product made from grain that is the mainstay of the Amazonian diet. “If there is no manioc on the table, there is no meal,” explains Souza. There are no stores in the village, no satellite dishes, and there are no outhouses. Using the woods that border their village as their toilet, it was clearly the largest bathroom facility I had ever seen. On the other hand, the men don’t have to worry about remembering to put the seat down. Although every day was an adventure, nothing compared with the nighttime jaunts. Our post-dinner sojourns, beginning around 8 p.m., pitched Souza and his searchlight against the dark horizon, scanning shoreline and trees desperately searching for something to entertain his charges. An all-pervasive quiet loomed, yet everything, including the sounds, seemed magnified: dolphins snorting, fish jumping, caimans slithering, monkeys howling -– all vying for attention. Eventually the flashlight, seemingly darting randomly above, below and beyond the trees, alighted (so to speak) on a caiman in the brush, his whole snout protruding for a moment before slinking away. Or perhaps instead the light reflected off a kingfisher’s eyes, temporarily blinding him so that we could drift in almost close enough to touch. Then for an encore, we watched a spider grab a dragonfly from a crack in a tree directly in front of us -– and diligently devour it. Did I mention it was pitch black? Once again, the refrain in my head: “How does Souza do that?” Either he has a seventh sense about the animals, or the Amazon Tourist Board set them up ahead of time. Whereas during the day, the trills, tweets and twerps of the birds dominate the landscape, at night it’s the croaks, caws and throaty outpourings of the frogs and caimans. In between our first launch at 6 a.m to our final return sometime after 9, we pretty much spend the rest of the time eating. The native foods, beautifully prepared and presented, are a surprise this far from civilization.

As much as that is a typical day, so are the exceptions. One particular day we got to sleep in until 6, still early enough to watch the sun pull itself over the forest, and late enough to feel the already oppressive heat seep into my lightweight, washable. anti-bug-treated blouse (though overall, the weather was much more comfortable than anticipated). We were going fishing. I sat with my Tom Sawyer fishing pole thinking the Amazon’s a long way from the Mississippi. I attached the chunks of beef to the end of the line thinking this was strange bait until I remembered our prey. Watching Souza rattle the water with his pole, I remembered that being quiet was the order of the day on most fishing sojourns. Still, I followed his lead -– make the quarry think there’s a wounded fish thrashing about -- and within a minute I knew I had snagged the big prize: at the end of my line was the famed carnivorous predator -– a 6” piranha.

Souza held it up to a tree and used it like a scissors to cut a branch in two. Just looking at its imposing teeth, we knew it came by its reputation honestly. Still, piranhas get a bad rep. The truth is unless they’re starving, or you’re bleeding, we’re really not in their food chain. Nonetheless, the fried piranhas we had that night as appetizers were scrumptious, their tiny bones crunchy and the meat flaky, proving the wise adage that more people eat piranhas than piranhas eat people –- at least in Amazonia. If You Go How to go. I flew United, one of several airlines that go nonstop from several U.S. cities to Sao Paulo, then transferred to TAM for the hop to Manaus. TAM airlines also has daily non-stop flights from Miami to Manaus. When to go. The January to June rainy season brings heavy but relatively brief downpours. Rivers rise dramatically -– often as high as 45 feet. The high water enables small boats to reach areas inaccessible at other times of year. During dry season, roughly July to December, rivers run shallow, and while white sand beaches –- excellent for a refreshing swim -– appear, most of the area is more arid and less lush. Best time to visit is April to September. For more information, call Latin American Escapes at 800-510-5999 or log onto latinamericanescapes.com. Some Caveats

Related Articles: (Posted 9-29-2011) |

|

This site is designed and maintained by WYNK Marketing. Send all technical issues to: support@wynkmarketing.com

|