|

|

|

|

|

Mary King's Close,

Edinburgh, Scotland: 400 Years of History

Where the Plague Comes Back to Life – Though No Longer Contagious Story by Fyllis Hockman Photographs courtesy of The Real Mary King's Close Consortium

The place, the time, the horror have been resurrected as one of Edinburgh's most unusual attractions. Archaeologically and historically accurate, the alleys you walk upon, the rooms you visit, the stories you hear are real. This is not a recreation; it is a resurrection of what already existed so many centuries ago. Beneath the City Chambers on Edinburgh's famous Royal Mile, lies Mary King's Close, a series of narrow, winding side streets with multi-level apartment houses looming on either side, which has been hidden for many years. In 1753, the houses at the top of the buildings were knocked down to make way for the then-new building. Parts of the lower sections were used as the foundation, leaving below a number of dark and mysterious underground alleyways steeped in mystery – and misery.

The exhibit breathes new life into this underground world dominated by death. Reconstructed as it was then – though without any contagious aspects – the Real Mary King's Close provides amazing insight into a period of history with which many are totally unfamiliar – and it's been preserved in an authentic environment and historically accurate depiction that defies most "commercial" historical reproductions. It is eerie meandering up and down along dark, circuitous unpaved passageways, beaten down earth floors (good walking shoes are a must; wheelchair accessible it is not) – past room after room, each with its own story to tell – a projection of people who lived in the Close in the mid-16th-19th centuries. I almost feel an intruder, the subtle lighting enhancing the effects of a shadowy past.

The inhabitants – ranging from those gracing a grand 16th century townhouse to plague victims of the 17th century to the third-generation saw makers who departed in 1902, when the last section was finally interred – are not composites of might-have-beens; the lives recounted are based on real people gleaned from primary documentation (written at the time) and preserved in the Scottish Office of Records and its archives.

Lighting conveys the supernatural nature of the attraction as much as does the narrative. Only "practicals" – original methods of lighting the dwellings – are used, re-creating the actual lighting conditions of the 17th-18th centuries. Candle light illuminates one room, while the glow of firelight casts its spell in another. A single low-watt light bulb brings others into hazy focus. The dark hallways are lit by lantern-like "bowats," providing only as much light as was necessary to light the streets at night. The lighting levels in each room are just enough to highlight its architectural features, furniture or inhabitants – no more or less than was available to the tenants at the time. The concept of atmospheric lighting takes on a whole new dimension. Rounding one curve reveals a large window, lit by a gloomy, greenish, unhealthy light. A doctor emerges, tending to bed-ridden figures, covered with sores, boils and diseased skin. It's the home of John Craig, a grave-digger who has already succumbed to the "visitation of the pestilence," his body awaiting "collection." His wife, Janet, and three sons suffer from varying stages of the deadly malady. The Doctor is lancing a boil on the eldest son, Johnnie, with a hot iron to seal and disinfect the wound. Repellant odors arising from the family chamber pot of vomit provide a little more "reality" than even today's cable TV has prepared me for. By the door there is bread, ale and coal delivered to the quarantined family. The townspeople want to ensure the afflicted stay in their homes, so the healthy have good reason to give generously. And therein lies the tragedy of Mary King's Close – much of its history parallels that of the plague. The epidemic struck its residents fiercely; as the deaths rose, the bodies accumulated outside to be carried away by those designated to perform the loathsome task. Mary King's Close was a pariah in the neighborhood – and ultimately fell victim to its own diseased fate. It disappeared, as well. With more than two dozen stops along the tour path – each accompanied by an intriguing bit of personal history – I became intimately acquainted with the residents who lived there.

Mary King herself, of course, who moved here with her four children in 1629 after her husband died. You'll get to meet her personally and boy, does she have some good stories to tell! While listening to the story of another early dweller, the narration is interrupted by a scream from across the way. We quickly run to see what happened. The widow Allison Rough, murder weapon in hand, is standing over her son-in-law Alexander Cant, a prominent Burgess of Edinburgh, whose body lay on the floor – the dowry agreement over which they have been fighting still in his hand. Events leading up to the murder, as well as its aftermath, are wound into a true-to-life rendition of Allison's memorable life. Similar stories, some enthralling, others bizarre – all authenticated by original documentation – abound as we wend our way around the windy, up-and-down corridors. Shifts in lighting reflect the various circumstances. Not to mention the assorted ghosts (the only residents not authenticated by original documentation) who are said to inhabit the property. Edinburgh native Jennifer West is awed by this backyard discovery. "This really brings to life all the stories I've heard over the years about this part of the city's history. It's hard to grasp that these underground chambers were once bustling street-side shops."

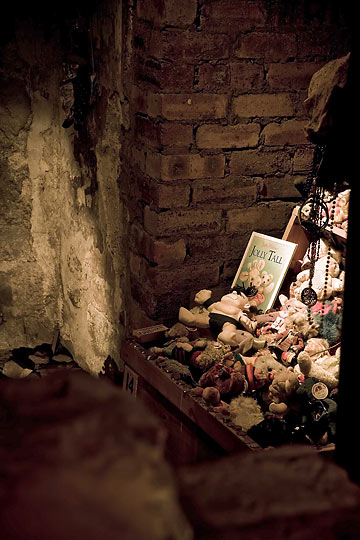

One of the most important – and saddest – among a multitude of rooms that witnessed much sadness is one in which eight-year-old Annie died of the plague in 1645. A Japanese psychic, visiting in 1992, could barely enter the room because of all the misery she felt there. As she turned away, she claimed to feel a tug at her leg. Annie, in rags with long dirty hair, was standing by the window, crying because she had lost her family, her dog and her doll. The psychic brought Annie a doll to comfort her – and people from around the world have been leaving trinkets and toys ever since. Key chains, jewelry, dolls, stuffed animals line the walls as a shrine to the sad little child who has long since passed away. "What a sad story," laments 10-year-old Harriet Peterson, visiting from London. She slowly adds the small stuffed teddy bear she is hugging to the other offerings. There was a lot of life lived within these buildings – and a lot of lives lost. As one of the most fascinating and unique walks – literally – through history I've yet to tread, the unsettling stories, the ethereal lighting, the serpentine alleyways remained with me, even as I explored the many other, more traditional sites of Historic Edinburgh. The Real Mary King's Close is open daily, with tours at 15-minute intervals. Price is adults, $23; children 5-15, $13; seniors and students, $20. For more information, please contact: VisitBritain at 1-877/899-8391 or visit www.realmarykingsclose.com. Related Articles: (Posted 9-5-2014) |

|

This site is designed and maintained by WYNK Marketing. Send all technical issues to: support@wynkmarketing.com

|