|

Airplane-Provided

Water, Ice, Coffee, or Tea

It's important

to stay hydrated while flying, but you're

better off BYOW (Bringing Your Own Water)

rather than grabbing a free drink from

the beverage cart.

Tests done

by the EPA a few years ago showed that

one out of every seven planes had tank

water that did not meet federal standards,

and in fact contained bacteria like

E. coli. Although beverage carts might

give you "bottled" water from

a large bottle, that bottle could have

been refilled using the tank water.

Coffee and tea are often made from the

same tank water, which is usually not

heated enough to kill germs. Ice is

also sometimes made on board, so it's

best to pass on that as well.

Tipping

Etiquette Around the Globe

As North

Americans, tipping is a reality, and

we are sensitive that the wait staff

receives their due. We generally like

to tip at the amount of 15% to 20%.

After all, the wait staff in North America

depends on it.

But if you are confused

about tipping in other destinations,

we determined what’s best to tip

outside of North America.

- Africa: 10% to 15%

- Australia/New Zealand:

None (the wait staff is well compensated

in their hourly salary

- Caribbean & Central

America: 10%

- China: None. (Tipping

is against the law)

- England: 10%

- Germany: 10%

- Ireland: 12%

- Italy: None (except

for great service, where you round

out bill)

- Japan: None. (tipping

is considered rude, but you always

offer your chef a beer)

- Middle East: 15%

- South America: 15

|

|

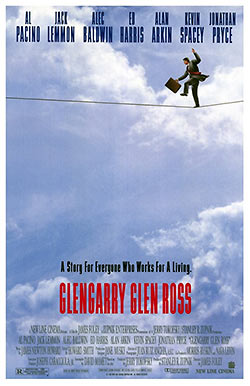

Time

Capsule Cinema

Director: James

Foley

Writers: David

Mamet (play), David Mamet (screenplay)

Cast: Al Pacino,

Jack Lemmon, Alec Baldwin, Alan Arkin, Ed Harris,

Kevin Spacey, Jonathan Pryce

1h 40 minutes. Aspect

ratio: 2.34:1

109 minutes. Widescreen;

1.85:1

Good

Mean Fun

A Look Back at Glengarry

Glen Ross

By Walt Mundkowsky

GLENGARRY GLEN ROSS

is David Mamet's most celebrated (a Pulitzer Prize)

and distilled play – slight but serviceable

plotting, expletive-filled dialogues of sourness

and spite, nary a female to be seen. Mamet focuses

on four real estate agents selling dubious Sun Belt

properties, and divides them into complementary

pairs: Ricky Roma, the champion closer, and Shelly

Levene, formerly productive but now fighting a long

dry spell; and Dave Moss, a malcontent and instigator,

and George Aaronow, clearly no longer equal to the

demands of the job. One of them burglarizes the

company office, stealing a batch of prized new leads

– that is the narrative engine.

Courtesy photo

Much of the play's

explosive impact derives from its confined settings.

The three encounters in Act One – Levene and

John Williamson, the office manager; Moss and Aaronow;

Roma and a prospective pigeon – happen in the

same restaurant, and all of Act Two takes place

in the ransacked office. Act Two is so tightly wound

as to be virtually tamper-proof, but Act One is

not so fortunate. It suffers from the "opening-out"

Hollywood typically imposes on hit dramas. Glancing

allusions must be spelled out (Levene's hospitalized

daughter, a brutalizing sales contest). Single scenes

must be broken into different locations to diminish

their claustrophobic charge, even if that also diffuses

their power. New material must be added (Levene's

and Aaronow's ineffectual sales pitches), even if

it adds nothing. Since Mamet served as screenwriter,

these alterations fit seamlessly among the original's

component parts, but they lessen the achievement.

Al Pacino and director James

Foley. Courtesy photo

Given director James

Foley's résumé at that time (RECKLESS;

AT CLOSE RANGE; WHO'S THAT GIRL; AFTER DARK, MY

SWEET) he seems a puzzling choice for this assignment.

And things get off to a rough start, with a visual

style more appropriate for one of Foley's hybrid

films noirs – luridly lit public telephones

and automobile interiors, and the obligatory backlit

nighttime thunderstorm. Several scenes are so clunkily

staged that attention-grabbing camera movement or

cutting is required to keep them afloat. And there

are egregious lunges at the audience, like the little

wink Roma gives Moss before moving in to snare his

mark. Foley does eventually calm down, but long

stretches are allowed to lapse into a kind of Ping-Pong

– shot/reverse shot flip-flops, the camera

sticking to the speaker. The resulting rhythms are

at odds with those of the actors (the Moss/Aaronow

scenes are especially disfigured). The transition

between Acts One and Two is cleverly managed, though,

with the elevated train functioning as a lateral

wipe. And Act Two is much more cogently directed;

the thoughtfully chosen camera positions enhance

the shifts in the balance of power.

These missteps in script

and direction are damaging but hardly fatal to the

enterprise. If anyone wants to see a film of this

play, it's because of Mamet's acidulous language

and the opportunity it affords skilled performers.

Both are splendidly intact. The heavyweight cast

delivers the goods without exception (acting is,

after all, selling), and at least two of the performances

are treasurable.

Al Pacino is arguably

too old to play Ricky Roma (the drama gains a dimension

when Roma is a decade or more younger than the other

salesmen), but he brings enormous vocal variety

to the character's lines – now most like a

weasel, now very like a whale. In particular, he

builds Roma's introductory spiel to his client with

such mastery that even Foley's inevitable shot changes

scarcely break the spell. And he holds back plenty

of power in reserve for the outbursts at the climax.

Kevin Spacey commands

a wide-ranging technical arsenal, along with the

disinclination to employ it glibly. He turns the

feed part of the office manager into something potent

and reptilian. His final desertion of Levene ("Why?"

–"Because I don't like you.") hits

harder than all the f-words Mamet strings together.

And Spacey can be physically delicate, to comic

effect; he handles the stack of precious new leads

as though he were a monk with a sacred artifact.

Courtesy photo

No other character

here is drawn with the vivid colors of Ricky Roma,

but each of them allows its proponent to leave a

strong impression. Alan Arkin's primary perceptions

as an actor are comic ones, and he makes George

Aaronow's frequent gaps in concentration deliciously

funny. They could be funnier still, were it not

for Foley's impatience; this is the performance

most impaired by the director's occasionally crass

cutting patterns. Dave Moss is the movie's attack

dog, and Ed Harris' customary intensity is never

merely loud, but always cognizant of larger designs.

Courtesy photo

One might have feared

that Shelly Levene would send Jack Lemmon straight

into his SAVE THE TIGER mode, but he steers a remarkably

clean course through the part's difficulties and

traps. I can imagine a Shelly Levene with a flintier

core, but Lemmon renders him as a particular human,

not as a sentimental "type."

An actor of Jonathan

Pryce's capabilities is pretty much wasted on the

rôle of Roma's dupe; Pryce expertly provides

the desired tone of rabbit-in-the-headlights vulnerability.

Alec Baldwin's turn, as a vulgar motivational speaker,

was created for the film; its absence wouldn't be

unbearable. As with Pryce, Baldwin supplies what

is needed, in this case stentorian egomania.

Flaws and all, this

film serves GLENGARRY GLEN ROSS well. It is unimaginable

that one would ever see such a cast assembled for

a theatrical run.

|