|

|

|

|

|

The Life and Times of an Irish

Royal

In Part 1 Brendan Parsons, the 7th Earl of Rosse, talked about his boyhood experiences during World War II, his return to Birr Castle, the Parsons family ancestral home, his school experience, and the path that led him to a post at the United Nations. This exclusive interview was conducted at Birr Castle and the following has been edited for content and continuity. Part 2: Return to Ireland &

Preserving the Legacy

Rosse: It was the most successful and longest assignment of my career. Unfortunately, I had to cut short my career for family reasons. Did you agree with all their actions? Rosse: I think one of the basic mistakes the U.N. made was basing itself in New York. It should be in a smaller, neutral country like Ireland or Switzerland, and not situated in the city of a major world power, and one to which access is only through a visa issued by the U.S. State Department. I've been refused entry into America many times, which caused great embarrassment when one is an official of the U.N.

Did your title impact on your service in the U.N.? Rosse: I found it perfectly natural to not announce my title. I served without the title because I considered it to be unnecessary baggage that would hinder rather than help. It would make me apart. I simply served as Brendan Parsons.

What was your advantage coming from Ireland? Rosse: I found it a tremendous advantage to come from Ireland. It is small and relatively neutral on a world scale, and rightly has abstained from an organization like NATO. That gives us more credibility or an entrée into most countries. A big super power like Britain or America seem to come in with baggage attached – baggage that is seen as trying to dominate. We don't come in with that baggage and don't have a political agenda. We are not trying to sell tanks, or aircraft, or submarines, and we don't attach strings to the advice we give.

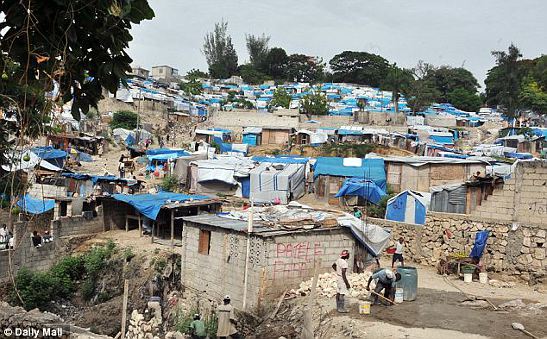

What was your personal objective? Rosse: I really wanted the U.N. to use my career to spend time on the ground, beyond Europe, in some of the poorest countries in the world to see what one could do to alleviate misery, stress, and disease. I wanted to accomplish this before the time came for one to return to Ireland. I wanted to know how people lived and what their real problems were. I wanted to see what, if anything, I could do to help people less fortunate than ourselves. For example, I had been to Haiti and had seen incredibly poor French-speaking blacks. I was able to communicate with them in French. Once they realized that I came from Ireland, and was neither British nor American, they bonded more easily with me. They would start chatting about their experiences, which helped one understand what their lives were like.

You mentioned that you had to cut short your U.N. career. What brought you back to Ireland, and in what condition did you find Birr Castle? Rosse: I had to retire from the U.N. and return to Ireland on my father's death. It was an awful horror for me to realize, after he passed away, how horrifically in debt the whole place was, and how much of the heritage had to be sold without losing the core heritage. This led one to define what the heritage was, and what was the key to it, and what one could do to preserve it. The estate today, for instance, is less than 10% the size it was when my father inherited it when he was a boy of twelve. At what point in your life were you made aware of your royal heritage and what responsibilities came with your title? Rosse: I certainly did realize after my relatively simple life in wartime England how very different things were in Ireland. It was a different world and one was increasingly aware of the luxury, the opulence, and the unlimited food after living in a country of rationing. But, as a child one was completely unaware of any responsibility that went with being the son of an earl. Eventually, however, I learned that it was our responsibility to make or earn or marry enough money to keep the whole place going.

Speaking of marriage, how did you meet your wife? Rosse: After three years in the Irish Guards, I then went to Oxford and that's where I met my future wife, Alison Margaret Cooke-Hurle. I met her at a party at college. We actually knew each other for a long time, and never forgot each other. I said I wouldn't marry until I was thirty and she beat me by two or three weeks. When you returned to Ireland, was it different from when you left to serve in the U.N.? Rosse: When I returned, I found it a very different country than the one I left – a country not only infinitely more prosperous, but infinitely more confidant. It also had a brand new work ethic dispelling the myth of the drunken patties in the bars not doing a day's work. I was appointed to a position with the Agency for Personal Service Overseas, the advisory council on development and cooperation, and started an international volunteer program. I found that those who applied to the program from Britain wouldn't work hard and so I had to send them back as the worst workers in Europe. That was a fantastic eye-opener for me.

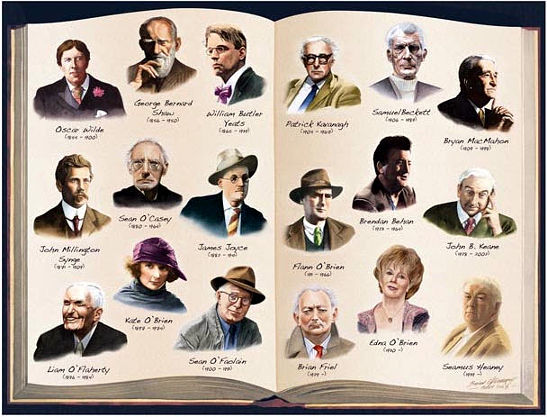

What bothers you the most about what other countries think of Ireland? Rosse: What interests me is the complete indifferent perception of Ireland and the Irish. The way the English saw Ireland, and the Irish, or the way the French saw Ireland and the Irish, was very different. France has a literary culture, as do the Russians, who saw the Irish as a literary people. However, in many countries, the Irish were just seen as Scots, Welsh, or English.

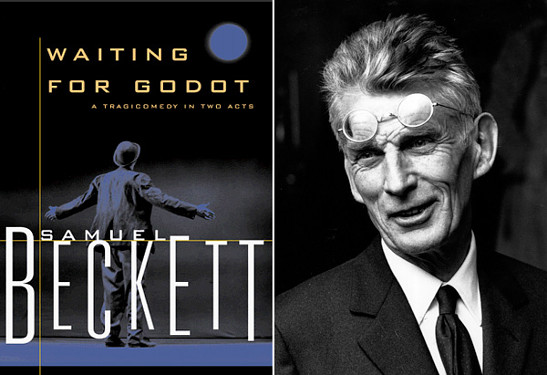

Can you give me an example of the lack of recognition of accomplishments? Rosse: My great-grandfather built a telescope, which was seen as the greatest telescope in the world. But it was seen as a British invention because he was seen as a Brit rather than an Irishman, despite the fact that he came from Ireland and built it in Ireland, and everyone who built it with him was from Birr. There wasn't one single Englishman involved in the whole process. But, despite that, it was seen as a great British success story and it was only failures that were seen as Irish. One of the things I try to improve is the unbalanced projection of that image because if people from Ireland had invented this, that, or the other, it must be a British or an American invention. That is how Irish accomplishments were presented. What action have you taken to change perceptions? Rosse: I tried to show that more has come out of Ireland than great music, poetry, and a literary tradition from the land of great writers. But even that needs clarification because what the world has seen is only what has been written in the English language versus what has been written in the Irish language. Although I don't have Irish myself as one of my languages, and very much regret it, I think even without those influences, one is immersed and impressed by the magic of the beautiful countryside. That moves one to love the land – the scenery, the romance, and the poetry. We must not only love our land, but must serve our land in different ways. When you've lectured abroad, was there one overriding question? Rosse: As an Irishman who went to America to lecture, I've had many problems of identity again. The first question I invariably was asked was, "Are you Catholic or are you Protestant?" I found that question so surprising, so unhelpful, and so sad, as it was always the dominant question. How would you describe your religious affiliation? Rosse: We are of a family that has been very ecumenical. We have always supported the Roman Catholic and Protestant churches. We have funded both branches of the church and were brought up to believe there aren't two different churches – but branches of the same church that share a great deal with those religions of a monotheistic nature, such as Islam and Judaism. We share more in common than actually divides us.

What are your thoughts on the war between the Protestants and Catholics known as "The Troubles? Rosse: This supposed war in Ireland between Protestants and Catholics that I found on returning to Ireland was complete nonsense. There were tragic problems in Northern Ireland, yes, but here, no. We simply had gone way, way beyond that. Ireland is a country that is one. It's an island as one. It's a people as one – with a vision that's one. That was far more important than this supposed wall – like a Berlin Wall - dividing Catholics and Protestants within Ireland. When I was serving as an Irishman in the U.N., we always worked together – as men, as women, as Protestants, as Catholics. We would celebrate St. Patrick's Day and other holidays happily together as one.

What steps are being taken the change the image? Rosse: At the time of my return, The Irish Tourist Board was trying to sell a lovely environmental picture of the mountains and valleys – the blues and the greens – a country with a great literary tradition, but certainly not a country known for its great gardens as opposed to great Georgian houses. To use the terminology of the tourist literature of the time: "Green valleys and mountains so blue, that a hundred thousand welcomes are waiting for you." The image of Ireland was presented as one of luscious valleys, beautiful poetry, great imagination, drama, and dance, but certainly not a country that had ever done anything ingenious or scientific or technological. It was a hard sell to try and get Americans, in particular, or the British to accept that anything like that had come out of Ireland.

Do you have a special childhood memory? Rosse: It was very early on when I learned to drive myself, even unofficially from age twelve on. Neither of my parents ever learned to drive. They had a driver. So, it became handy to have someone else to take the cars away from the front door. I was taught to drive very young, and to take one's parents around later and to get around. So, I knew the estate probably better than my younger brother or anyone else. I love land. I've always had a passion for land – whether woods or farmland or whatever, and that has stayed with me to this day.

We have about 30 seconds left on this tape. Is there something you would like to say in bringing our interview, which I've enjoyed immensely, to a close? Rosse: Well, I hope I said something useful. I wish to build a new, better bond with the communities in the United States, in particular. I hope they see the evolution of a new Ireland that appreciates all the elements of our society, culture and community, and is carrying no baggage, or any negativity, or anything reflecting an artificial division of religion or anything else between us. Thank you so much for this fascinating journey into your extraordinary life… Related Articles: |

This site is designed and maintained by WYNK Marketing. Send all technical issues to: support@wynkmarketing.com

|

hat was your experience like serving in the United Nations?

hat was your experience like serving in the United Nations?