|

|

|

|

Straddling the Rhine, Basel is a transmutation of three countries Images of Basel:

Technically, there are two train station complexes, but they exist in three countries. The main station, Basel SBB, sits in the old town area and is one of the most trafficked railway hubs in all of Switzerland, but French Railways (SNCF) maintain an annex station directly connected to it, so one can actually go through a border-crossing and officially enter French territory, without leaving the complex. The French station sits on Swiss land, but the tracks and the trains are French territory.

The other main station, Basel Badischer Bahnhof, sits on the other side of the city, across the Rhine and still technically in Switzerland, although operated by Deutsche Bahn, the German railway company. Once you leave the lobby and go through the tunnel to the trains, you are technically in Germany. The land is still Switzerland, but the trains and the platforms are German territory. In Basel Badischer Bahnhof, I already seem to occupy three countries at once. In one of the original historic halls, I investigate "crossover cuisine" at a restaurant named Les Gareçons. It’s a play on words. Normally spelled garçons, meaning boys or waiters, the word contains an ‘e’ because gare means station. I opt for pasta, just so I can claim I ate Italian food in a French restaurant, in a German train station, in Switzerland. Art Crosses Over with Nature From there, every sphere of influence crosses over into everything else. When it comes to art merging with nature, the interior of a building merging with its exterior landscape, Fondation Beyeler fuses the macrocosm with the microscosm. From Badischer Bahnhof, it’s only a short tram ride, to the town of Riehen, half a mile from the German border. The illustrious art collector Ernst Beyeler chose this site in his home town. Renzo Piano designed the building and its architecture blends in with the environment before one even enters. Except for the open-air tiled glass roof, which seemingly floats, the exterior of the building is constructed of Red Porphyr stone from Argentina, which complements the green grass outside.

And from outside, I look down from the top of a terraced lawn, gaze across a pond, through a giant window and directly into the front gallery space. Once inside that space, looking back out, it becomes obvious that the building was designed to merge with the natural surroundings. Looking through the glass window, floor to ceiling, one views a tranquil pond outside. Lilies float on top of the water as if waiting for something to happen. Since the entire complex is sunk into the ground, the French oak floor is level with the pond outside in a seamless transition. Beyond the pond, the proportionately terraced lawn rises up from the water and into the surrounding trees. Looking out the window, it feels like I’m viewing a painting. Inside the gallery, Monet’s The Water-lily Pond spans nine meters along the wall, complimenting the scenery outside. From anyone’s perspective, it is clear that the structure was designed to accommodate the art and the landscape, rather than just function as a grandiose building.

In another part of the museum, a long hallway, also with floor-to-ceiling windows, faces west onto a parcel of land next door, mostly green and golden farmland, as it stretches to the Wiese River. Beyond the waterway, Tüllinger Hill creeps up in the background. As a project, the building, in every respect, seems to crossover into the natural world. Every component of the experience is part of the same ecosystem. Alchemy of the Everyday According to one biographer, the mystic Rudolf Steiner often felt like he was functioning between two different realms. Maybe that meant the spiritual and the material, I don’t know, but the Vitra Design Museum and Campus put together the world’s first ever Steiner retrospective.

Steiner had his hands in quite a few disciplines. He started the Waldorf Schools. He innovated organic architecture and designed new breeds of furniture. He corresponded with everyone from Kafka to Kandinsky and he founded the philosophy of Anthroposophy. He was an original crossover hero, blurring the boundaries between design, architecture, spirituality, natural science, farming, biocosmetics, experimental dance and inner transformation. An easy bus ride from Basel takes me across the border of Germany to the Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein, location of the Steiner exhibit, Alchemy of the Everyday. The Vitra building itself is a dynamic deconstructivist tour de force by Frank Gehry, the structure that essentially vaulted him to the international stage over twenty years ago. One can say it organically detonates from the grassy landscape of the property.

Through May of 2012, Alchemy takes place inside. Steiner’s biography covers one wall, a complete chronology including letters, pamphlets and other correspondence. Furniture he designed sits on display. Architectural models, performance documentation, sketches and pedagogical material highlight much of the exhibit. There are films, diagrams of organic farming techniques and countless examples of individuals that Steiner inspired. Outside, across the rest of the Vitra campus, continuous tours in German, French, English and Italian are offered. Several other notable architects designed other buildings here--the factories, the research facilities, an old fire station-turned-exhibition space and even a geodesic dome from Buckminster Fuller himself. Leading Swiss architectural legends, Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron, designed the Vitra House and Lounge Chair Atelier Shop, across the way from the Gehry building, where one can look at decades of avant-garde furniture. Even the bus stop, designed by Jasper Morrison, is part of the overall landscape.

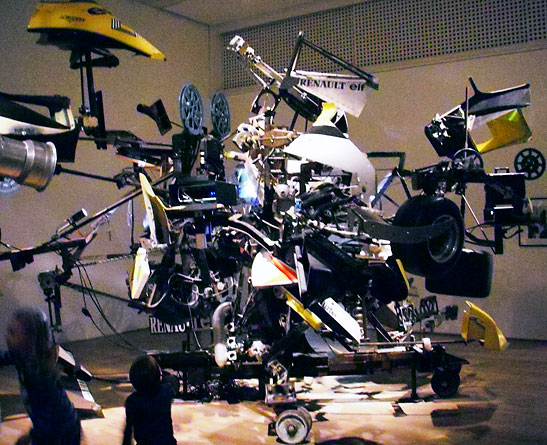

A Glorious Racket The kinetic machine sculptures of Jean Tinguely create a sonic racket, a symphony of cacophonous delight. Constructed from artifact discarded by society, his machines glorify public spaces across Europe, but a museum dedicated to his life’s work sits along the Rhine, in Basel. From the Old Town area, one simply crosses the bridge and meanders down a promenade beside the Rhine, eventually arriving at Solitude Park. Next door sits Museum Tinguely, a Mario Botta-designed structure of Alsatian limestone, commanding a serious presence. Bounded by the river, the park and a freeway, the building relates with all of those entities. One can suggest it sits between solitude, noise and water.

Each side of the building mingles with the already-existing environment. The west side of the structure features a wide porch that opens out onto the park. The side facing the Rhine extends out from the main building and functions more like a natural extension of the riverbank. Everyone who enters the museum has to pass through this area, beckoning them to stop and view the softly flowing waters of the Rhine. The façade facing the highway is large, multistory and somewhat monolithic, acting as a sound barrier that prevents the traffic noise from reaching the other side facing the park. The fourth side, facing north, overlooks another street and features a covered alcove, directing visitors to either the entrance or the park. Inside, there is plenty of room for Tinguely’s gargantuan machines. Each machine is controllable, that is, you stomp on a floor-button and then wait ten seconds for the machine to kick in. The children enjoy it even more than the adults.

Crossing From New To Old In Basel, opposites fuse. I have explored the young architecture, but I end with the ageless. In Basel’s old town, one discovers five ubiquitous heads directing you on five different city walks. Each one is named after a leading figure from Basel’s past. There’s the Erasmus Walk, the Hans Holbein Walk, the Paracelsus Walk, the Thomas Platter Walk and the Jacob Burckhardt Walk. I slither in the footsteps of giants. These hidden guides are always there, beneath the surface, in a strange, arcane way.

Each walk shows the city and its evolution from a different perspective. The medieval alchemist Paracelsus, for instance, guides you up steep alleys, down obscure side streets, through both commercial and residential areas, concluding, appropriately, at the Pharmaceutical Museum, where you can see ancient medical instruments used by folks from the era of Paracelsus himself. Burckhardt was a nineteenth century art scholar and historian, so his walk is titled, Past and Present in Harmony. Contrasting many different styles of architecture, from gothic to the current era, the walk includes the Tinguely Fountain and the Historical Museum. In Basel, even the alleys are multilingual. I can hear voices in many languages. The stories they tell are infinite. In Basel, there is no end and no beginning.

Related Articles: |

|

Your tea adventures are especially interesting because I've always associated tea with British etiquette or a bevy of women wearing dainty victorian costumes and sipping tea with their little pinky sticking out. To see Tea from a man's perspective brings new light in a man's psyche. I've been among the many silent admirers of your writings for a long time here at Traveling Boy. Thanks for your very interesting perspectives about your travels. Keep it up! --- Rodger, B. of Whittier, CA, USA

|

This site is designed and maintained by WYNK Marketing. Send all technical issues to: support@wynkmarketing.com

|