|

|

|

|

|

The

Blues……

On hands and knees, Hubert found his way through the kitchen and into a back bedroom and hid beneath a bed until the police arrived. He laughed about it then, but the memory was crystal clear, "When the Wolf went to holler 'Evil' that's when the shots started back there."

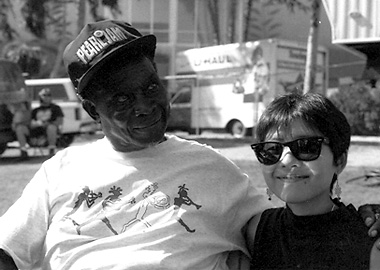

Whiskey, women and money; too much, not enough or any combination of the three has been the flash point for some of our greatest blues recordings; not to mention fist fights; barroom brawls and assorted gun play. David 'Honeyboy' Edwards 1915 - 2011 David 'Honeyboy' Edwards was one of America's living treasures and one of the last of our founding fathers of traditional Delta blues. His road was filled with adventure, hardships and more than a few, near-death experiences. Honeyboy related, once at a picnic in Tennessee "they had a big table, gambling, shooting dice," as the liquor flowed and money changed hands he recalled, "they got to arguing, fighting." One excitable patron upset that "snake eyes" always seemed focused on him, registered a complaint. Edwards remembered it as an extremely large-caliber complaint. "The pistols were shooting." and just like in the movies, the first thing that happened, "they shot the light out." Honeyboy was standing right there when the opening salvo got everyone's attention. "Money was all on the table and every time the pistol would shoot, it would light up the table (he starts shaking his head) and I was trying to grab the money." Ducking down to just above eye level with the gaming surface and to avoid any possible stray round or ricochet, he would wait. "Every time somebody'd shoot," he said, "it'd throw a big light." You could almost see the glint of those muzzle flashes in his eyes as he spoke, "That's when I could see, when one'd shoot." Think about that, he would stand, scoop up as much of the cash as he could before ducking back beneath the table. He repeated this scenario multiple times until the gunmen both emptied their revolvers. Honeyboy continued to shake his head as he remembered, "I coulda' got shot, I coulda' got killed. I was young and crazy, I was just taking that chance of getting that money or die, you know?" Dumb-struck, I'm staring at this man, and all I can think of is, "How much did you get?"

When he realizes what I've asked, Honeyboy looks right at me and just laughed, "Oh, it wasn't that much, fifteen or twenty dollars, trying to get all that change up, you know." One of the most impressive qualities I noticed about David Edwards was his remarkable ability to recall dates, events and literally, the history of the blues. And according to his own account, his introduction to the road began one fateful weekend in 1932 when, at the age of 17, he heard a bluesman perform at a local house party. His life would never be the same. "Joe Williams was out there playing for a country dance on a Saturday night and I went over there where he was playing. I kept looking at him and he said, 'Can you play?' I said, 'I can play a little.' He passed the guitar to me and I started to strum 'cause I had a good lick, you know? And he said, 'Yeah, and I can learn you, too.' So, he come to my father's house that Sunday morning, we eat breakfast and sat around. He played guitar and he asked my father, 'Can Honey go with me out to Greenwood?' We were only about two miles from Greenwood. My father said, 'I don't care, he ain't nothin to do on the farm. He can go if he want to.' I got my brother-in-law's guitar and followed him. I never did brought his guitar back, I kept a-going with Joe Williams."

It would be the beginning of Edward's lifelong journey. "When I first started out with Joe, I played some in the streets, little clubs, cafe's and joints, just everywhere, anywhere you can make something. Joe couldn't read or write or nothin', but he had a good mind and he could think of songs to sing. He had a good mind but didn't have no kind of education, but he could think good and he wouldn't forget nothin." In order to further his own education, Honeyboy would soon find company with another blues traveller. "After I left Big Joe the last of '32, in '33 and '34 I was with Tommy McClennan and '35 too. I was around Greenwood and Tommy was around Greenwood too. Tommy and Robert Petway, we all just go in and out together. Sometime I'd work with Tommy, sometime Tommy'd work with Robert. We all know'd each other, played with each other, you know?" Charley Patton, one of the most influential of the Delta's elders, had a profound effect on a young Honeyboy. Patton's creative guitar style and turn of a phrase was an inspiration to, or imitated by almost every bluesman to come out of the South and Honeyboy was no exception. "I was with Charley Patton a little while before he died in '34. I know'd him in '33, he was at Marigold, Mississippi out from Dockery, he was still on the farm at Dockery Plantation. He married this young girl, Bertha, that was his wife Bertha, and the year he died, in '34 they had went to Jackson and Bertha had recorded the 'Yellow Bee Blues.' She sung and that was the last recording he done." The Sweet Life When Honeyboy reflects on his early days in blues he has to laugh. "Before I married, I didn't do nothin' but play guitar and gamble. That's all I done. I had a gang of women's, you know. I had two or three, they was working and had good jobs." Living the sweet life was nice but David Edwards was never very far from the music or the players who made it. "I used to live in Memphis and I used to play with some of the Memphis Jug Band, Big Walter Horton, Will Shade (Son Brimmer), Little Frank Stokes and Old Man Stokes. I was young then but I know'd them all. Me and Big Walter Horton was pretty close together. I was two years older than Big Walter but he was a good harp blower ever since he was 14. I met him in Memphis, Tennessee, he was maybe 15 years old. I met him in Handy's Park." Charlie Musselwhite, who also credits Joe Williams and Will Shade as influences, once described himself as 'slack-jawed' the first time he witnessed some of the early greats on stage. So it shouldn't be surprising that harp players, to this day, still try to match Horton's technique and tone. Honeyboy doesn't think it will happen.

"Can't do it. Both of them Walters had a good tone. Little Walter Jacobs had a tone that Big Walter didn't have. Little Walter had like a Louisiana style, down on the bayou music but he had his own style of playing harmonica. He had a good, full sound. Little Walter had a better, fuller sound than Big Walter had, but Big Walter played more harp than Little Walter played. You understand me? He knew more riffs. But Little Walter had the best tone." "I carried Little Walter Jacobs with me in 1945, he come there with me in '45. In the winter of '45 I went back south, I was scared of the cold weather. Walter told me, he said, 'Well Honey,' he say, 'I ain't goin' back. I'm gonna' lay around and hang around here awhile.' He liked it up there. And I left. In '46 in the fall I heard Walter's records. Walter had recorded with Muddy Waters. I said, 'That boy's done recorded'.....I say, 'I'm goin' back' I say, 'I'm going where I can do me somethin'. So when I come back Walter was hooked up with Muddy Waters." Everyone who heard Little Walter play knew he was ahead of his time, but those who ran with him knew his time wasn't long. "Walter could play that harp, the boy was good, but he lived too fast, too fast. He got down to Chicago and was makin' money. He was tall, a nice-lookin' boy and had a lot of women's and a big Cadillac. It went to his head." Gone to soon, Little Walter would die from injuries suffered in a street fight and Honeyboy remembers only too well, Big Walter's life-long suffering. "Big Walter was sick all his life. He was sickly, puny-like, you know? He drank a whole lot of whiskey. Oh, he was a heavy drinker." Speaking of an early demise, Edwards spent a short period of time in the mid 30's playing and touring with the bluesman considered by most to be the 'King of the Delta Blues' players, Robert Johnson. "In 1937, Robert was 26 and I was 22. Robert was about four years older than me. The first time I met him was on the streets. I didn't really know who he was 'cause I hadn't ever met him, but I heard about him. I got a cousin who lived in Tunica, Mississippi, she was Robert's girlfriend, and every time I go to see my cousin she'd tell me about Robert. 'Do you know Robert? Robert plays guitar.' I say, 'No, I don't know Robert.' She say, 'Robert Johnson, he goes by Robert Johnson, Robert Lonnie Johnson, he wears so many damn names, I don't know.' (laughing) And so, when I met him on the streets and he was playin' he told the people he was Robert Johnson and he had just came from Austin, Texas. That would have been the fall of 1937, and he was playin' on the streets. A lady come up there, she said, 'Listen sir, play me Terraplane Blues and I'll give you a dime,' like that. Just country people standing around drinking whiskey, listening to that music and he said, 'That's my record, lady.' She said, 'Well play it then for me,' and he started to playing it and she said, 'I believe that is that man's record.' He played it just like the record, you know." Tragically Johnson would be dead within a year, but David Edwards' career was just starting to pick up speed. "I was so fast myself, I went around a whole lot myself, but as long as he (Johnson) was around Greenwood I'd hang around with him. I'd go where he was playin' at and we'd go to a couple of whiskey houses there in Greenwood and whore houses where they sell whiskey, you know? Two or three woman's there at Greenwood had good-time houses, women's be hangin' around and men drinkin' a lot of white whiskey and we sittin' there playin' for them, you know? Good time houses, good time Charlie." Well into his 90's Edwards continued to live the blues. Not a lifestyle for the weak of heart, Honeyboy always insisted he was going to slow down. He was also the first to admit that the blues were here before he was and would still be around long after he was gone. "Blues is not gonna' go nowhere. There's a lot of young people playing the blues too, now. They're gettin' right into it. And a lot of festivals bringin' in some of the young people to the blues." The endless cycle of human suffering guarantees that the blues, in one form or another, will always endure. "Blues come along ways to what I've been experiencing because I'm old, I've been here a long time. Blues come from slavery time and what I mean by slavery time, the peoples used to work in the field and sing holler songs. Ohhh…Ohhhh…trying to make the day. In the 20's they started recording like Mama Rainey, Bessie Smith, Ida Cox, Blind Lemon and they named it the blues. In the early days, it was players like Texas Alexander and Lonnie Johnson and then they just come on in the 40's and the blues got wide. I came up playin' the lonesome, slow blues. There's two or three different ways you can play the blues. You can play a slow blues, the low-down dirty blues, the Mississippi blues or you take the same blues and make it uptempo, a shuffle, up-tempo beat, you know? In the later years I worked a lot of taverns and I started playing some of the up tempo blues. Just raise the tempo on it. See what I mean? Still it's the blues." David 'Honeyboy' Edwards was a living, breathing piece of American history. A National Treasure who summed up his life as a bluesman, philosophically. "Blues is a feeling. You can start playing the blues and the feeling comes down on you sometime. It's a feeling, from the heart. Mine. And when I was young, I used to start playing the blues and I'd play a couple of numbers and I'd get right up and put up my guitar case and start to walk, go catch me a ride and go to the next town. They wouldn't let me stay nowhere, that's what the blues do for me. I wouldn't stay nowhere, that's why I went so much. I'd be here this week, and next week I'd be somewhere's else. That guitar just kept me goin', wouldn't let me stay." Lucky for us. Joe Willie "Pinetop" Perkins 1913 - 2011

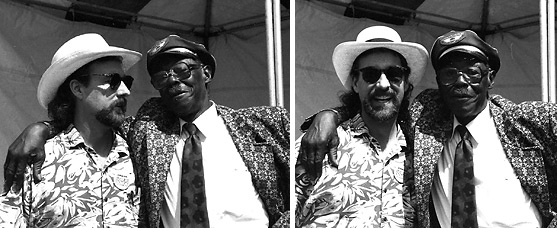

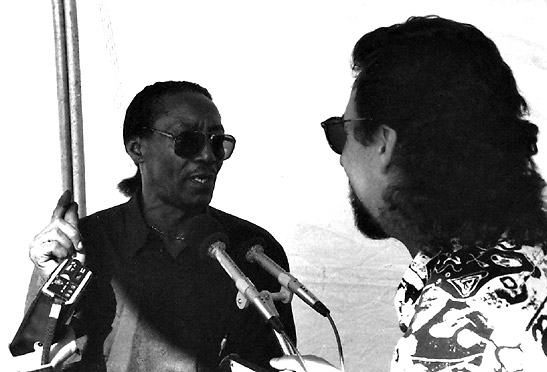

Over the years I ran into Mr. Perkins on several occasions and he always had stories for me….the last time we spoke I asked him about his constant touring. Country dances, traditional picnics and fish fries; did you ever play in houses of ill repute? "Well, I played in some houses, don't know if they were whore houses or not. They might have been! (he starts laughing) I played in everything; in the Blues Brothers movie and all that stuff…Angel Heart." From the beginning you were running with a pretty fast crowd, literally some of the all-time blues greats. Robert Nighthawk, Sonny Boy Williamson, Earl Hooker, Big Joe Williams… "Big Joe Williams? Oh man, I loved that Joe. He never did sing with me none. I love that Joe, man. My best memory of Big Joe was he was a good singer, he was really good. I loved the way he sung." Tell us a little about your association with Robert Nighthawk? "Oh man, I played with Robert about four years. And what took me from Robert Nighthawk when I was over in Helena, Arkansas…we was advertising Bright Star Flour. Mr. Max Moore, Interstate Grocery Man at KFFA, he heard me and told Sonny Boy (Williamson) 'Looky here man, hey, go over there and get him. I want him to play for me.' He loved the way I played piano. Dudlow (Robert Taylor) was playing, Mr. 5x5 (not to be confused with Jimmy Rushing) was playing then."

Perkins played on a number of the most popular live radio broadcasts out of Helena. As mentioned, the Bright Star Flour program with Nighthawk, and of course the most prominent from that time was sponsored by King Biscuit Flour. The show featured numerous stars of the day, like Sonny Boy Williamson, Houston Stackhouse and James 'Peck' Curtis. In the late 40's and early 50's, Pinetop would once again hit the tour circuit with Robert Nighthawk, eventually ending up in Chicago at the renown '708 Club.' He would also back the legendary slide guitarist in the studio, on some of Nighthawk's last recordings for Chess. Another long-time friend of Pinetop's, Willie Dixon produced and played bass on those memorable Nighthawk sessions. You also ran with Earl Hooker for awhile…. "Earl Hooker? Boy, oh me and him got together years ago. He was 13 years old when we started playing together. And I was young and had nuthin' of nuthin'! (laughing) That was way back, I was about 20 or something then, and Earl was real young. But he was in bad shape. (Hooker suffered from tuberculosis and died in an Illinois Sanitarium at age 40.) He was sent to the hospital, and every once in awhile he'd come back around and say, 'I'm well now.' He wouldn't be discharged; he'd done slipped out of the hospital. (laughing) The doctor didn't turn him loose; he'd turn his own self loose. He'd come back, 'I'm well now!' And no sooner than he'd get back, they'd send him right back to the hospital. So the last time, Muddy Waters heard me playin' with him." Is that when you replaced Otis Spann in Muddy's band? "Well, in a way I did. Otis had quit him and I started playin' in the band with him. That was '69. 1969, so I played with him up until '80." What was it like playing in Muddy's band? "Oh, I loved playing in Muddy's band, man. I loved it 'cause he had the 'stomp-down' blues stuff. That's why I loved it."

One of Pinetop's long-time friends, Buddy Guy, told me a wonderful story about his piano playing protégé. "Just before Jimmy Rogers' died, he (Pinetop) used to play with Jimmy a lot, at my club in Chicago. So I walks in the club before they start playing, and I went to say 'hi' to Pinetop and he took his leg and throw'd it up on the bar like this." (Buddy hoists his leg up near the table) "I say, 'what's that for?' And they had that monitor on his leg (Buddy begins to laugh)... from the police. I say, 'who did you kill?' He said, 'Nobody!' I say, 'what's wrong with you?' He said, 'simple drunk, they got me just simple drunk.' The only time they let him come out at night, is if he was working, they wouldn't stop him from playing the keyboard. I said, 'you wasn't drivin'?' He said, 'no, I was just simple drunk, walkin'.' So then he takes me over there and sits down and said, 'they told me to stop drinkin', he say, 'but Buddy' and he had this shot of whiskey in his hand. He say, 'if I stop drinkin…' now this has been about 15 - 18 years ago. He say, 'if I stop drinkin' (Buddy snaps his fingers) …that's IT!' I say, 'DON'T stop drinkin' then, then keep on drinkin'. And about three or four years before he passed away, they had him at the club again and he came in, they was rolling him out in a wheel chair and it was raining. I say I hadn't hollered at him, I want to holler at him before he go, and I say, 'wait a minute 'Top, I wanna' say hi before you go.' He say, 'I ain't goin' nowhere, I'm goin' outside to smoke.' And I think he was 93 or something. And I say, 'if you can smoke at 93, people should stop saying cigarettes are not good for you.' (laughs) Early in 2011, the world was Pinetop's oyster. Although in his 90's he was still vital, still productive and still doing what he loved the most. He had just been recognized with a 'best traditional blues album' Grammy for a recording he'd done with old friend, Willie 'Big Eyes' Smith entitled, 'Joined at the Hip'. A memorable evening and lasting moment that embraced the man before generations of his friends, fellow musicians and fans. You have to think that the extended applause that night was not only for his music and his remarkable career, but an outpouring of love and respect for a legendary and gentle man. Thanks, 'Top. Rest in Peace. Willie "Big Eyes" Smith 1936 - 2011

I would be remiss if I didn't mention Bob Brunning 1942 -2011 British bassist who was a founding member of Fleetwood Mac and also played with the Savoy Brown Blues Band. Doyle Bramhall 1949 - 2011 who played with both Jimmie and Stevie Ray Vaughan and helped put Austin, Texas on everyone's blues map. Keith "Keef" Hartley 1944 - 2011 drummer with John Mayall's band. Alan Rubin 1943 - 2011 trumpeter for the Blues Brothers Eddie Kirkland 1923 - 2011 Clarence Clemons 1942 - 2011 Big Jack Johnson 1940 - 2011 Gary Moore 1952 - 2011 Coco Robicheaux 1947 - 2011 And the dozens of others I've failed to list. So do yourself a favor, go out and pick up a couple of new or old recordings from some of your favorite musicians. Put your feet up, slap on that old pair of headphones, close your eyes and spend a few moments enjoying what's really important. A life well-lived. Related Articles: |

|

|

![]()

Stay tuned.

This site is designed and maintained by WYNK Marketing. Send all technical issues to: support@wynkmarketing.com

|

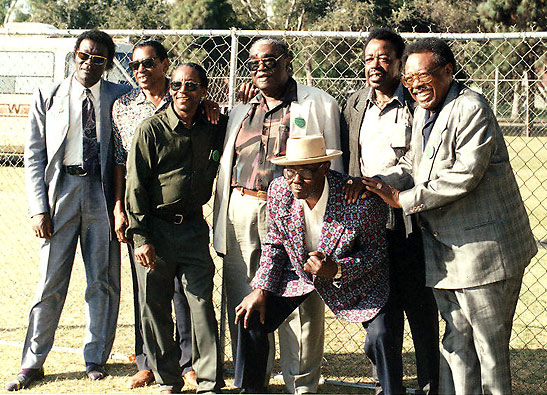

hen the Blues community reflects back on 2011, it will be with great

sadness. We lost so many incredibly gifted musicians during the year.

The loss of each one of these legendary individuals has been felt by

millions of admiring friends and fans the world over. So, instead of

grieving, or maybe as my way of grieving, I'd just like to share some

of their stories and photographs. To a person, these artists were dynamic,

forces of nature that paved the way for every blues man and woman that

followed; and fortunately for us, through their music they will remain

influential for generations to come.

hen the Blues community reflects back on 2011, it will be with great

sadness. We lost so many incredibly gifted musicians during the year.

The loss of each one of these legendary individuals has been felt by

millions of admiring friends and fans the world over. So, instead of

grieving, or maybe as my way of grieving, I'd just like to share some

of their stories and photographs. To a person, these artists were dynamic,

forces of nature that paved the way for every blues man and woman that

followed; and fortunately for us, through their music they will remain

influential for generations to come.