|

|

|

|

|

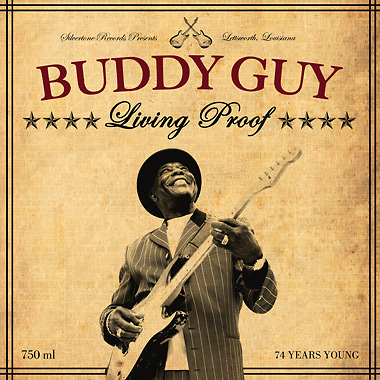

Buddy Guy is without question, one of the most influential guitarists in the last 50 years. He's been honored in the Oval Office of the White House and toured with the Rolling Stones. As the 'go-to' session guitarist for two of Chicago's premier blues labels, Cobra and Chess, Guy has played with every bluesman from Little Walter and Howlin' Wolf to Muddy Waters and Pinetop Perkins. He just picked up his 6th Grammy Award and his status in the music world is so prominent that it took two legends (Eric Clapton and B.B. King) to induct him into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. It's the Blues according to Buddy Guy. I

Love the Life I Live, and Live the Life I Love!

If you're still not convinced, pick up a copy of his latest CD, 'Living Proof.' Guy makes 74 look and sound like the new 44. Fresh off his 6th Grammy win, we sat down to talk right after the earthquake, tsunami and on-going nuclear catastrophe in Japan. Buddy was seriously concerned for his fans throughout Asia and expressed hope he wouldn't have to postpone a summer tour there. "I'm not afraid," he told me. "If anybody else goes there, I'm going to go." I lament that it seems the world is going through some tough times right now and Buddy just shakes his head. "But you know man; this might be a wakeup call. You know we got along without that stuff? We're always coming up with something we really don't need and have no control over. So why are we constantly building them? Now they say, 'they're here.' (America) You know we're capable of an earthquake like Japan, right here! And you have no control if something happens, so why put it there? Why jump in the lake and you know you can't swim?" Uhhh…okay wait, I know this one. I look down at my paperwork as Buddy continues, "My mother used to tell me that man, when I was a little boy. 'If you're going to learn how to swim don't jump in that deep water. You get in water from your waist up and come back to the bank to learn how to swim.' You have to agree that that is pretty sage advice… and Buddy smiles. "Ohhh, I don't think they ever told me anything wrong, even though as a kid I thought it WAS wrong…until I grew up." Let's talk about those early years. Was your first exposure to music from the church? "Well, if you know what I'm talking about, I'm a share-cropper's son. And the churches we came up in they couldn't afford no kind of instrument or nothing like that. And my grandparents before they passed away, when they found out I was stretching rubber bands and trying to make guitars and things they don't know nobody. Because the guitar and harmonica, until Little Walter and Muddy and them amplified that thing man, it was obsolete in the music store. You would walk into a music store before Little Walter made 'Juke,' there wasn't no big music stores like you got now, Guitar Centers and all these big stores with instruments. There was one little corner store and he had two guitars and a harmonica laying there. And you say, 'how much is the harmonica?' and the guy say, 'I don't know man, give me anything to get it out the way, 'cause it's just in the way.' And Little Walter made a comment before he made 'Juke' he said, 'if George Washington Carver can get out a peanut, what he got out of a peanut, I can get somethin' out of this harmonica.' And he did." Marion Walter Jacobs aka Little Walter, would go on to record a string of hits after 'Juke' and is to this day, considered by most to be the best amplified harp player that ever lived. He would die violently in Chicago from the injuries he'd suffered during a street brawl. Little Walter was only 37. "I'm trying to get Horner and Lee Oskar to at least come up with a harmonica in his name. Because before he made Juke all harmonica's was a dime and five cents. And before Leo (Fender) and Les Paul amplified the acoustic guitar it was just a Saturday Night fish fry instrument, 'cause you couldn't hear it, people was talking loud."

I'd heard stories that Buddy had created his first guitar out of wire strands pulled from his mother's door and window screens and wondered if those stories were true. "I was in Louisiana you know, and I didn't know what runnin' water was till I was almost 17. Of course we didn't have any electricity, so it was an old wooden window and when you'd open it they got some mosquitoes in Louisiana that'd take you out of the room. So she would buy this piece of screen and make me tack it up there so she could leave it open at night. It would get extremely hot in Louisiana man, you know?" Buddy begins to smile as he remembers, "I found out that little wire could be stretched and heard better than that rubber band. I wasn't stealin' it, I was just borrowing it, but it would break every time I tried to finger it. I would take a board and a little lighter fluid can, flat like your little tape machine here and try to take four strings (screen strands) and put it on there. But I couldn't finger it, I'd just pull 'em tight as I can and sit there and ring 'em with one finger like that." Buddy's last two albums, 'Skin Deep' and his latest, 'Living Proof' have both won critical acclaim, with the latter winning Buddy an abundance of new fans. It seems your music, at least on the last two releases, has become more personalized. Like making the statement, 'this is who I am, this is what I do…this is Buddy Guy. My question, I guess is, 'would that be a fair assessment and does it have anything to do with your working relationship with writer/ producer Tom Hambridge? "This is I would say 96 or 97% or even better, new material. When I was there with the Willie Dixon and the Chess and the Cobra (record labels) everybody wanted a piece of the cake. And it wasn't ever hardly, Buddy show me something new. Working with Tom is like, when he came in, like you came in now, he comes in with a pad even when were holding a conversation. I'd say 80% of the songs he wrote, came through me talking about the screen wire or where I'm from and he started noting this down. And he'd tell me, 'Man, every time you talk you're writing a song.' He takes me in the studio and says, 'this room belongs to you now.' Eric Clapton pulled my leg to this, when I got to know him. He said, 'When I was making hit records and playing the blues in the 60's, I was so high, layin' down on the floor, I didn't listen to nobody. I played Eric Clapton. So the best of my younger years, I wouldn't say the best, because the best might be now, who knows? I was more of a listener, and I'm like saying, 'well if it's Willie Dixon saying its wrong, its wrong. If Willie Dixon say its right, it's right.' And in the meantime, in the back of my mind, something tells me, 'Buddy if you'd a went on and just did the Buddy Guy you'd a been there before, who knows? Maybe Hendrix or maybe not, but at least I wouldn't have nobody to blame but myself. So I never had the freedom in those early days as I've got with Tom and like you say, most of this, 85 to 90% of these lyrics is something I was talking about and didn't even think he was writing the song down about it." Let's talk a little about one of your earliest professional gigs in Louisiana, playing with the 'Big Poppa' John Tilley Band. "Uhh… (laughs) As a matter-of- fact that's the only time I ever got fired, from day work to anything else. You know I was too shy to sing, but if you call me into here like now (just three people) I'd blow you out of here. And he (Big Poppa) came to the service station where I was pumping gas and he say, 'I heard you could sing and play.' I say, 'Plug it up!' For two people I wasn't afraid. He say, 'How much you makin' at this service station?' I think I was makin' less than ten dollars a week. I wanted to go to school and my mother had taken a stroke and a share-cropper couldn't send you to high school, so when he offered me double what I was makin' I say, 'Oh, I can send myself to school in the daytime and play at night.' And I accepted it." (laughing) "And I went to play that first night, I know it was a Tuesday night, I never will forget that. And he hooked the microphone up like you got in front of my face now and I say, 'okay, give me the microphone, but you got to turn my back to the audience and put the mike to the wall.' He say, 'No you gotta' sing out here to the audience.' I say, 'Not tonight!' And I turned my back, and the Royals (later became Hank Ballard and the Midnighters) had a record out called 'Work with me Annie. And I sung it and the people's going crazy and he (Big Poppa) says, 'turn around.' I couldn't turn around. When I did, I was cryin' 'cause I was too shy. And he fired me. And that's the only time I ever been fired. One of my best friends which was in school, he was Baton Rouge, he passed away about 10 or 12 years ago, he said, 'if you take a shot of this schoolboy scotch you'll turn around.' That was Dr. Tichenor's antiseptic in a Coke bottle. And I went back 6 or 7 weeks after that and he gave me that and I turned around and sung, 'Work with me, Annie.' And I worked with him until almost before I left there. I started my own little three-piece band before I left and went to Chicago." Liquid courage comes in all forms. One of B.B. King's first radio shows he said was sponsored by a medicinal miracle called 'Pepticon.' And I've heard more than a few stories about a tonic known as 'Hadacol…' Buddy starts laughing… "Yea, yea, Hadacol, uh, uh, what's his name…Jerry Lee Lewis, I just did a record with him (Hadacol Boogie) He said that, and they wanted to know what was that? But I knew in Louisiana, what it was. Hadacol was some kind of medication that had a little kick to it." A little kick? B.B. said he found out later, 'Pepticon' contained about 12 percent alcohol. "But it was only wine, back then. Do you know the average musician, when I went to Chicago September the 25th 1957, do you know I thought I would see Jimmy Reed's home, Muddy Water's home, Howlin' Wolf, Little Walter's home and wanted to see how well they were living. Do you know I went to Jimmy Reed's house and sat on his couch…and went straight to the floor! And I said to myself, 'is it worth it?' But they was having so much fun, all they was playin' for was a good-looking woman and a drink. That was the pay. And the love they had for the music that I'm still trying to carry on today." Let's talk about that. Looking at your tour schedule, you're constantly on the road. How do you maintain that type of schedule? "Well, I used to pick cotton. And every time I think on the road, 'it's hard,' all you got to do is think, 'we didn't have machinery.' All I got to do is tell my band members, I say, 'Guys,' some of them know about it, but they never did it, I say, 'all I got to do is think about my mom and dad used to come home in the evening after they done worked the whole year long.' We didn't have the technology you got now, where you pass a farm and see them watering it, with a machine…watering it. We had to pray for rain and sun, and if we didn't have that perfectly…they had worked the whole year for nothing. So every time I think the road is hard, I say, 'wait a minute.' (laughing) At least I get paid now. I didn't get paid in the early days, but now I get paid. I can't complain. When I got six, seven, eight years old and could catch a fish they was the happiest parents you ever seen. 'Cause they know I done caught three or four fish. By the way, when I caught my fish back then, if he's big enough to bite the hook, he's big enough to cook. (laughing) Good thing Tom ain't here, he'd write that down." (laughing) Can we talk a little about the bars and clubs of Chicago? Let's start with the 708 Club…. "The building is still there. They tried to get me to revive it, but it's in one of those neighborhoods, now days with the DUI's and non-smoking it's hurt all blues clubs. I own the largest blues club in Chicago and its downtown. It's survived because it's right by the biggest hotel in Chicago, the Hilton. In other words, them good old days when you used to drive ten or fifteen miles you don't do that no more with the new DUI (laws). When I first started coming here (Los Angeles) they had the Ash Grove, several blues clubs; the Palomino. Yeah, I came here a lot, but a lot of those places have gone and I don't think they're ever coming back… Back in those days the 24/7 steel mills and stockyards in Chicago, we used to have to play at 7 o'clock in the morning and you couldn't get in there…in the blues club. Because the guy who works at the steel mill got off at eight. That was his time to party and he went back to work at twelve that night. So he didn't get a chance to see us and Muddy Waters play. So Muddy, myself and all us got together and said, 'let's start a Blue Monday Jam.' And it worked." I've heard some horrific stories from players like Snooky Pryor, Willie Dixon, Otis Rush, Charlie Musselwhite and a lot of others about the wildness that occurred in some of Chicago's bars and after-hours blues joints. One place they all referenced called, 'the Bucket O' Blood.' You ever play there? (Laughing) "I think that (still laughing) I think if you really wanted to name 'em, they had more than one. Yeah, I played in one...that's the first time I ever saw a guy get stabbed with a ice pick. It was one called the Squeeze Club, but anytime somebody got shot or hurt in there, they called it a 'bucket o' blood.' They had one, you remember Freddie King, right? He made a record called, 'Hideaway.' Well that club, that was the name of the club after they changed it. It was once called, uh, Tay May's, it was called Mel's Hideaway, I think. It was Mel's Hideaway when this guy went in there early in the morning in Chicago, like I said, in the heyday of the steel mills and the stockyards, everything was 24/7. And this guy walks in there around 7 o'clock in the morning and orders two Budweiser's. And the only guy in there was the bartender and he was filling the cooler. You take the cold beer out and put the hot beer in and put the cold beer on top, so you can sell the cold beer to the guy that walks in. This guy walks in and orders two Buds. The bar guy serves him the two Buds and went back to fillin' his box up. I guess he thought the guy was waiting on somebody else to come drink the other Bud with him but the guy had a paper sack…with a woman's head in it. Yea…and when the guy come up out of the box (Buddy starts to chuckle, probably because of my facial tic and doofus-like expression) he saw the guy take the woman's head out and set it beside the Budweiser, sittin' there drinking his, like I'm talking to you now. That was the club Freddie King named the Hideaway song after, that was it. That was Roosevelt Road." I'm breathing through my mouth, slack-jawed and can't remember my next question. Buddy continues, "You know most of the time, all that was about was a woman or a man." I wanted to say, 'or pieces thereof,' but I couldn't produce the saliva. "It wasn't about the drug thing, you could walk damn near anywhere you wanted to go man…it was always about that. And then sometimes those guys was the best of friends, sit there and drink a half-pint, out of a bottle together. Those was the two who started to shootin' for something, 'you said-I said, you're my best friend but I'll blow your brains out.' I never could figure out, how they would do that. How could you drink out of the same bottle till you get a buzz…and THEN want to kill one another?" I remember the photo of Little Walter with that gash stitched across his forehead and Buddy nods and begins to laugh, "Junior Wells had one too."

Could you talk a little about some of the session work during your time with Chess? You were the 'go-to' guitarist for the label. "For the blues...they had some great guitar players there. But most of those guitar players man, Matt Murphy's still around, Wayne Bennett passed away. Dave and Louis Myers were two brothers and a few more I didn't get to know. All of them passed on. But every time they would call them and they got a chance to play in the session with Wolf, Muddy, Walter or somebody they felt it was my time to show off. But it was my time; I'm speaking of Buddy Guy now, to be in class. And that's how I got to play in all them. I'd never want to run Muddy Waters out of the studio; I wanted to make Muddy Waters look good. And they said, 'if you want it played right, call Buddy.'" One case in point…. "For instance, Howlin' Wolf had been in the studio I think, two days doing this record called, uh I done forget the title of it." Buddy sings, "I shoulda' quit you and went on to Mexico." (Killing Floor) "And they said, Leonard Chess say, 'Go call Buddy!' 'Cause Leonard would hum this stuff to ya.' And a lot of guitar players had lead sheets. And since I don't read music, I don't. 'If you want it played right, call Buddy.' And they called me in at seven in the morning, they had been there all that night and I walked in the studio and said, 'what is that?' And Leonard hummed that, 'bumbum,bum, bumda-dabum, bum.' I say, 'Let's go!' Two takes and I went on home." Leonard Chess hummed the guitar riffs to you? "Yea, yea…actually some of Muddy's earlier stuff, Leonard Chess was pattin' the drum on it. They didn't have a backbeat, it was just a foot pat on it. He was creative (Leonard) but he couldn't play it. But when Fred Below (Chicago drummer known for his early work with Little Walter) came along, he had that thing I had, you know? All you had to do was tell him and he was, 'I got it.'" The music from those days still sounds so good to me, why do you think it holds up so well? "Back then it was a reel-to-reel tape with a razor blade. If they wanted a beat, they cut it out with a razor blade. When you go into a studio now; I went in the studio here in L.A. when I was doing 'Feels Like Rain' and they had so much technology. We taped a couple of cuts, I forget what tune it was and I went to use the bathroom, and came out and I said, 'Who's that?' They say, 'That's you! That's what you just finished doing.' Well back in Chess days, I knew it was me 'cause they didn't have all the tech they got now. They'd be playin' a replay to see could they get it better, most of the time was get it worse, if you didn't take that first or second take on it, anyway." Let's talk a little about the Blues and its amazing journey from America to Britain and back again. "That music was played throughout the South. Those were the days when the blues was predominately in the South, now they call it the 'chitlin circuit,' back then it didn't. Because we didn't have all the different music we got now. It was all (Buddy spells it out) M-U-S-I-C. It wasn't no rock, and acid rock and soul and all that stuff. Everything was R & B back then. By the way, the British guys started playing the blues, and I don't know if you remember the television show, Shindig? (I do indeed) Well, it was going pretty big here and the Stones was getting famous and selling and getting popular and more popular every night and every day. And they (Shindig producers) went after the Stones to do the Shindig and they didn't want to do it. And finally they agreed and say, 'we'll do Shindig if you let us bring Muddy Waters.' And they asked them, 'Who was Muddy Waters? And Mick Jagger got offended; 'say you mean to tell me you don't know who Muddy Waters is? We named ourselves after one of his famous records, 'Rolling Stone.'" You were part of the American Folk Blues Festivals that toured Europe in the 60's ('62-'69) Muddy Waters, Sonny Boy Williamson, John Lee Hooker, Willie Dixon, Memphis Slim and Sippie Wallace just to mention a few...the list is endless. And that was some of the first 'live' exposure for so many of the young players and bands (Stones, Yardbirds, Ten Years After, and John Mayall's Bluesbreakers) that brought blues back to American shores. Even Jimi Hendrix ended up in Europe. "Well, he had to go to England before he got exposed. They told us all, 'bring it on.' It was a German guy… two German guys, Horst Lippmann & Fritz Rau, who created the American Folk Blues Festival. And when the British got it, when it first exploded America was saying, 'it was a British Invasion and it was new.' And they were coming in here saying, 'Wait a minute, this is not new! You got this, you had this all the time and you just didn't know it. This is Howlin' Wolf, this is Muddy Waters.' And they was all asking, 'Who is that?' This is Son House, this is Fred McDowell. This is music that these guys start collecting and start playing it and turn'd that amplifier up where no record company here wanted to hear that amp that loud. Because Leonard Chess kicked me out, and then he say, 'C'mon in here.' When Leonard Chess found out what it was doin' he sent Willie Dixon to my house, said 'Go get him!' I went there and he bent over. He had the album, he bent over and say, 'I want you to kick me right in the behind!' I say, 'What's wrong with you?' He say, 'you been tryin' to get me this stuff all the time, and I was too f#@&%$! dumb to know what you had.'" When it's all said and done, how do you hope history will remember Buddy Guy? "I want people to know that, as I say when I go play, 'I know there's always someone who come in and don't know who I am, never heard me. But I want you to go away and say after you see me, 'I didn't like him, I didn't like what he sung, I didn't like the way he played. But I could tell…he gave me everything he had.' 'Cause every time I go to the stage, I intend to give you everything, the best that I got. As my parents told me, 'Buddy don't ever be the best in town, just be the best until the best come around.'" And I can pretty much guarantee that the man is coming your way in the very near future, no matter where you live. You can check out his tour schedule or maybe the next time you're in Chicago; stop in at Buddy's place, Legends. Just tell them you're in town to check out 'the best.' Related Articles: |

|

|

![]()

Stay tuned.

This site is designed and maintained by WYNK Marketing. Send all technical issues to: support@wynkmarketing.com

|