|

Honeyboy

Edwards

A Witness to the Blues

avid

'Honeyboy' Edwards has been in fast company for most of his life. His

running buddies have included the seminal roots of Delta Blues. Charley

Patton, Robert Johnson, Son House, Willie Brown, Tommy McClennan, Tommy

Johnson and Robert Petway were just a few of the musicians that Edwards

called friends. He's spent a lifetime sharing street corners, working

juke houses and rolling the dice with the legends of blues, both past

and present. avid

'Honeyboy' Edwards has been in fast company for most of his life. His

running buddies have included the seminal roots of Delta Blues. Charley

Patton, Robert Johnson, Son House, Willie Brown, Tommy McClennan, Tommy

Johnson and Robert Petway were just a few of the musicians that Edwards

called friends. He's spent a lifetime sharing street corners, working

juke houses and rolling the dice with the legends of blues, both past

and present.

Honeyboy Edwards & T.E. Mattox

Edwards has outlived his peers, and most of his friends, but shows little

sign of slowing down. When pressed, he'll admit to some 'pretty good

action' as far as his guitar work is concerned, but even more impressive

is his phenomenal recollection of dates, events and first-person accounts

of the blues and its originators. According to Edwards, his introduction

to the road began one fateful weekend in 1932 when, at the age of 17,

he heard a blues man perform at a local house party. His life would

never be the same.

"Joe Williams was out there playing for a country dance on a Saturday

night and I went over there where he was playing. I kept looking at

him and he said, 'Can you play?' I said, 'I can play a little.' He passed

the guitar to me and I started to strum 'cause I had a good lick, you

know? And he said, 'Yeah, and I can learn you, too.'

So, he come to my father's house that Sunday morning, we eat breakfast

and sat around. He played guitar and he asked my father, 'Can Honey

go with me out to Greenwood?' We were only about two miles from Greenwood.

My father said, 'I don't care, he ain't nothin to do on the farm. He

can go if he want to.' I got my brother-in-law's guitar and followed

him. I never did brought his guitar back, I kept a-going with Joe Williams."

It would be the beginning of a journey Edwards, now in his nineties,

finds more rewarding than ever.

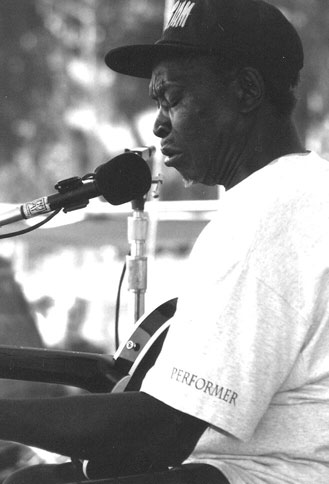

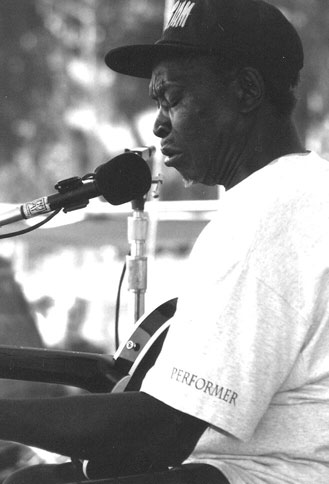

Honeyboy Edwards performs in the summer of 1988

|

"When I first started out with Joe, I played

some in the streets, little clubs, cafe's and joints, just everywhere,

anywhere you can make something. Joe couldn't read or write or nothin',

but he had a good mind and he could think of songs to sing. He had a

good mind but didn't have no kind of education, but he could think good

and he wouldn't forget nothin."

In order to further his own education, Honeyboy would soon find company

with another blues traveller.

"After I left Big Joe the last of '32, in '33 and '34 I was with

Tommy McClennan. I was around Greenwood and Tommy was around Greenwood

too. Tommy and Robert Petway, we all just go in and out together. Sometime

I'd work with Tommy, sometime Tommy'd work with Robert. We all know'd

each other, played with each other, you know?"

While Edwards, McClennan and Petway were just getting started, one Delta

elder, Charley Patton, was already considered a living legend. Patton

was one of the most versatile and influential delta musicians of the

era, and Honeyboy was a quick study.

"I was with Charley Patton a little while before he died in '34.

I know'd him in '33, he was at Marigold, Mississippi out from Dockery.

He was still on the farm at Dockery Plantation. He married this young

girl, Bertha, that was his wife Bertha, and the year he died, in '34

they had went to Jackson and Bertha had recorded the 'Yellow Bee Blues.'

She sung and that was the last recording he done."

The Sweet Life

When Honeyboy reflects on his early days in blues he has to laugh.

"Before I married, I didn't do nothin' but play guitar and gamble.

That's all I done. I had a gang of women's, you know. I had two or three,

they was working and had good jobs."

Living the sweet life was nice but David Edwards was never very far

from the music or the players who created it.

"I used to live in Memphis and I used to play with some of the

Memphis Jug Band, Big Walter Horton, Will Shade, Son Brimmer, Little

Frank Stokes and Old Man Stokes. I was young then but I know'd them

all. Me and Big Walter Horton was pretty close together. I was two years

older than Big Walter but he was a good harp blower ever since he was

14. I met him in Memphis, Tennessee, he was maybe 15 years old. I met

him in Handy's Park."

Charlie Musselwhite who also credits Joe Williams and Will Shade as

influences, once described himself as 'slack-jawed' the first time he

saw Walter Horton blow. So it shouldn't be surprising that harp players,

to this day, still try to match Horton's technique and tone. Honeyboy

doesn't think it will happen.

"Can't do it. Both of them Walters had a good tone. Little Walter

Jacobs had a tone that Big Walter didn't have. Little Walter had like

a Louisiana style, down on the bayou music but he had his own style

of playing harmonica. He had a good, full sound. Little Walter had a

better, fuller sound than Big Walter had, but Big Walter played more

harp than Little Walter played. You understand me? He knew more riffs.

But Little Walter had the best tone."

Gone to soon, Little Walter would die from injuries suffered in a fight

and Honeyboy remembers only too well, Big Walter's life-long suffering.

"Big Walter was sick all his life. He was sickly, puney-like, you

know? He drank a whole lot of whiskey. Oh, he was a heavy drinker."

Speaking of gone to soon, Edwards spent a short period of time playing

and touring with the bluesman considered by most to be the 'King of

the Delta Blues' players, Robert Johnson.

"In 1937, Robert was 26 and I was 22. Robert was about four years

older than me. The first time I met him was on the streets. I didn't

really know who he was 'cause I hadn't ever met him, but I heard about

him. I got a cousin who lived in Tunica, Mississippi, she was Robert's

girlfriend, and every time I go to see my cousin she'd tell me about

Robert. 'Do you know Robert? Robert plays guitar.' I say, 'No, I don't

know Robert.' She say, 'Robert Johnson, he goes by Robert Johnson, Robert

Lonnie Johnson, he wears so many damn names, I don't know.' (laughing)

And so, when I met him on the streets and he was playin' he told the

people he was Robert Johnson and he had just came from Austin, Texas.

That would have been the fall of 1937, and he was playin' on the streets.

A lady come up there, she said, 'Listen sir, play me Terraplane Blues

and I'll give you a dime,' like that. Just country people standing around

drinking whiskey, listening to that music and he said, 'That's my record,

lady.' She said, 'Well play it then for me,' and he started to playing

it and she said, 'I believe that is that man's record.' He played it

just like the record, you know."

Tragically Johnson would be dead within a year, but David Edwards' career

was just starting to pick up speed.

"I was so fast myself, I went around a whole lot myself, but as

long as he (Johnson) was around Greenwood I'd hang around with him.

I'd go where he was playin' at and we'd go to a couple of whiskey houses

there in Greenwood and whore houses where they sell whiskey, you know?

Two or three woman's there at Greenwood had good-time houses, women's

be hangin' around and men drinkin' a lot of white whiskey and we sittin'

there playin' for them, you know? Good time houses, good time Charlie."

It wouldn't be until the end of WWII that Honeyboy would finally make

his first trip to Chicago.

"I carried Little Walter Jacobs with me in 1945, he come there

with me in '45. In the winter of '45 I went back south, I was scared

of the cold weather. Walter told me, he said, 'Well Honey, he say, I

ain't goin' back. I'm gonna' lay around and hang around here awhile.'

He liked it up there. And I left. In '46 in the fall I heard Walter's

records. Walter had recorded with Muddy Waters. I said, 'That boy's

done recorded'...I say, 'I'm goin' back' I say, 'I'm going where I can

do me somethin'. So when I come back Walter was hooked up with Muddy

Waters."

Everyone who heard Little Walter play, knew he was ahead of his time,

but those who knew him personally realized his time wasn't long.

"Walter could play that harp, the boy was good, but he lived too

fast, too fast. He got down to Chicago and was makin' money. He was

a nice-lookin' boy and had a lot of women's and a big Cadillac. It went

to his head."

Throughout his travels, Edwards has witnessed both the rise and demise

of some of music's most dynamic personalities. But in his eyes, it was

just a part of life on the road.

"I used to go so much, I wouldn't stay nowhere," but Memphis

became Honeyboy central when his sisters moved to the area in the late

'40's and early '50's. With family close by you could usually find him

"playing West Memphis every Friday and Saturday night. I used to

play with B.B.King in 1950, '51. He was in West Memphis, Arkansas. He

was broadcasting over there in Memphis at WDIA station, but he was living

in West Memphis. Me and my wife used to go over there every Friday and

Saturday night and I'd sit in with him. He had one little old number

he'd made about Miss Martha King. He made that for Sam Phillips too,

I think. Sun's.

And I was in Memphis when Elvis Presley made his first little record

there. Presley was working in Memphis driving a construction truck.

This white boy got famous, he come from Tupelo, Mississippi. He made

one little old number for Sam Phillips, Sun's. It didn't do nothin',

but when the song got out here (California) someway it made a hit when

it came out here."

The Delta-born Presley knew firsthand the appeal and heart-felt emotions

of blues music and would start his career by covering some of the era's

most prolific black artists. It would be those Elvis remakes that would

eventually expose a segregated white America to the music of Arthur

Crudup, Willie Mae Thornton and Herman Parker.

Honeyboy remembers Elvis "shakin' and goin' on, but he couldn't

play nothin'. Doin' the swing dance and people went for it and he got

famous, but he didn't learn how to play guitar for a long time. I run

in on him but we never played together, I run in on him several times.

I know'd him, I used to see him when he was workin'. He used to come

out to Jackson Ave. sometime when he was laying steel back in 1950."

Fifty-eight

years later, Edwards is a blues survivor. His road continues to run

through every type of blues venue imaginable. From small bars and clubs

to huge fairground and festival events and the occasional recording

studio. It's not a lifestyle for the weak of heart and Honeyboy insists

he's going to slow down. He's also the first to admit that the blues

were here before he was and will still be around long after he's gone. Fifty-eight

years later, Edwards is a blues survivor. His road continues to run

through every type of blues venue imaginable. From small bars and clubs

to huge fairground and festival events and the occasional recording

studio. It's not a lifestyle for the weak of heart and Honeyboy insists

he's going to slow down. He's also the first to admit that the blues

were here before he was and will still be around long after he's gone.

"Blues is not gonna' go nowhere. You take years ago when a lot

of disco's slowed the blues up a little bit. But the disco didn't stay

in long, see? And then the blues come right on back, alive, and it got

worser. It got worser. There's a lot of young people playing the blues

too, now. They're gettin' right into it. And a lot of festivals bringin'

in some of the young people to the blues."

The never-ending cycle of human suffering ensures that the blues, in

one form or another, will always endure.

"Blues come along ways to what I've been experiencing because I'm

old, I've been here a long time. Blues come from slavery time and what

I mean by slavery time, the people's used to work in the field and sing

holler songs. Ohhh, Ohhhh, trying to make the day. In the 20's they

started recording like Mama Rainey, Bessie Smith, Ida Cox, Blind Lemon

and they named it the blues."

"In the early days, it was players like Texas Alexander and Lonnie

Johnson and then they just come on in the 40's and the blues got wide.

I came up playin' the lonesome, slow blues. There's two or three different

ways you can play the blues. You can play a slow blues, the low-down

dirty blues, the Mississippi blues or you take the same blues and make

it up tempo, a shuffle, up-tempo beat, you know? In the later years

I worked a lot of taverns and I started playing some of the up tempo

blues. Just raise the tempo on it. See what I mean? Still it's the blues."

David 'Honeyboy' Edwards is a living, breathing piece of American history.

A National Treasure who sums up his life as a blues journeyman, philosophically.

"Blues is a feeling. You can start playing the blues and the feeling

comes down on you sometime. It's a feeling, from the heart. Mine. And

when I was young, I used to start playing the blues and I'd play a couple

of numbers and I'd get right up and put up my guitar case and start

to walk, go catch me a ride and go to the next town. They wouldn't let

me stay nowhere, that's what the blues do for me. I wouldn't stay no

where, that's why I went so much. I'd be here this week, and next week

I'd be somewhere's else. That guitar just kept me goin', wouldn't let

me stay."

Lucky for us.

|

![]()

Fifty-eight

years later, Edwards is a blues survivor. His road continues to run

through every type of blues venue imaginable. From small bars and clubs

to huge fairground and festival events and the occasional recording

studio. It's not a lifestyle for the weak of heart and Honeyboy insists

he's going to slow down. He's also the first to admit that the blues

were here before he was and will still be around long after he's gone.

Fifty-eight

years later, Edwards is a blues survivor. His road continues to run

through every type of blues venue imaginable. From small bars and clubs

to huge fairground and festival events and the occasional recording

studio. It's not a lifestyle for the weak of heart and Honeyboy insists

he's going to slow down. He's also the first to admit that the blues

were here before he was and will still be around long after he's gone.