By Fyllis Hockman

Talbot County, Maryland is old. Very old. One of the earliest buildings dates back to 1682, a Quaker Meeting House, the site of the oldest religious building still in use in the United States. But more than the origin of its buildings, three favorite sons of the county encapsulate its history in different but fascinating ways. Two were symbols of the Revolutionary War, the other of the Civil War. One a resident (though he wouldn’t have been considered so at the time…) of St. Michael’s, another Oxford, and the third his very own island, Tilghman.

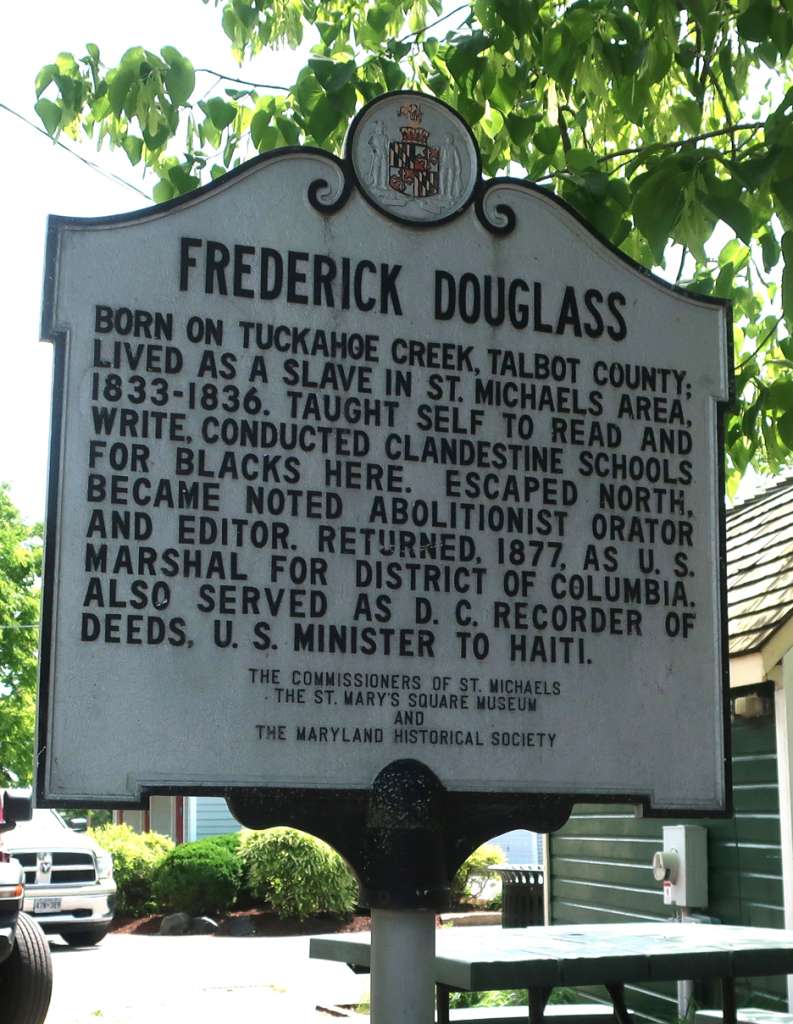

Let’s start with one of my favorite destinations in Washington, DC. Located high atop the Anacostia River is Cedar Hill, the home of Frederick Douglass, a structure which matches the man in stature, eloquence and grandeur. Douglass, whom many consider “the most eminent and respected African American of the 19th century,” was a runaway slave in 1838 at the age of 20. And it was an aha moment on a recent trip to Talbot County, Maryland to discover that it was that very county of his slave birth from which he ultimately escaped.

Several tours take you past his childhood home, areas he played in as a boy, and farms where he was indentured, as well as those areas he visited when he returned in his ’60s. Douglass recounted in multiple autobiographies the influence of Talbot County on his life and consequently, the influence of Douglass across the county and across the decades.

In St. Michael’s, we drove along the road he walked when his master, Thomas Auld, in 1834 rented the difficult Douglass to Edward Covey, known as the cruelest “slave breaker” in the neighborhood. I wanted to drive the seven miles as slowly as possible so as to put off the metaphorical but inevitable lashes as long as possible. Douglass endured many.

From St. John’s Methodist Church, you can see the field of the Covey Farm where Douglass toiled in between his oft-earned punishments. Another area of Covey’s personal homestead, where his whip was often engaged, literally – and ironically – was located in a part of town known at Mount Misery. More ironically, Mt. Misery Road is juxtaposed to nearby Mt. Pleasant Landing. The extreme evil that is evident throughout Douglass’s early life is symbolic of all enslaved people and should reverberate through to today as too many wish to re-write history.

It’s one thing to intellectually know about the many cruelties of slavery – another to experience it through the eyes of an actual person who happened to also be a slave. Douglass finally escaped in 1838 to Baltimore and went on to become the icon we all revere today. But he did return to Talbot County – having said of his hometown, “It is always a fact of some importance to know where a man is born, if, indeed, it be important to know anything about him.” That tour was one of triumph.

Another famous name associated with Talbot County, Robert Morris, is one who unlike Douglass, spent little time there – just two years originally in his early teens – and yet the most famous inn in the area bears his name. He went on to become a very prominent merchant and as one of the nation’s Founding Fathers, was considered the “financier of the American Revolution.” He also was one of only two men who signed all three of the nation’s principal documents: the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation and the Constitution.

The Robert Morris Inn, which opened in 1710 as the River View House – the oldest full-service inn in America – still retains so much of that century’s ambience that I could easily picture him in the room next to mine. Not really such a far-fetched idea as he lived there as a child. He also later dined there with a friend of his – George Washington. Four of the 314-year-old rooms were indeed slept in by not only those Founding Fathers but many other dignitaries of the day – and since. As much of the original structure remains today, the inn exudes history.

As does the town it’s located in. Oxford, founded in 1670 and still looking much the same, is more than just a step back in time – it’s a visceral re-emergence into a pre-Revolutionary War timeline.

A town where people still do not lock their doors; so quiet it closes up by 9 p.m. on a Saturday night; old homes, waterways and few cars contribute to the sense of calm and isolation that pervades the town, a veritable throwback to congenial Americana. Benches at almost every street corner invite you to sit, relax and watch either worn working boats traversing multiple waterways or old homes such as the Barnaby House, dating back to 1770, with 95% of its original structure still intact. There are many of them. Even more inviting? A sign that says, “Welcome to our porch.” As one shopkeeper opined, commenting on the cohesiveness of the community, “I have to go downtown to find out what my plans are each day.”

Less a household name (except perhaps in Talbot County) is Mathew Tilghman.

Matthew Tilghman came to Talbot much later than the other two gentlemen and without some of their distinction though he, too, served honorably in the American Revolution, as well as the head of the Maryland delegation to the Continental Congress. He later served as a state senator. By a fluke of family providence, he inherited in the mid-18th century a tiny island at the end of the Chesapeake Bay, three miles long by one mile wide, that became a sanctuary for oyster-dredging waterman – and hasn’t moved much beyond since. Tilghman Island – whose street signs are shaped like little boats – makes Oxford look like a metropolitan thoroughfare.

The sign at Dogwood Harbor – basically a small pier – reads: Home of the last working fleet of skipjacks (First built in the 1890s for dredging oysters) in North America and Chesapeake Bay commercial watercraft. One of those is the Minnie V, a Chesapeake Bay skipjack built in 1906 and listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Down Walnut Creek Road with its vast expanse of the Chesapeake, several newer boats perpetuate the island’s heritage.

Sure, the Robert Morris Inn screams its connection to the financier; as does Tilghman Island its benefactor – but the many areas of Talbot County connected to Frederick Douglas are more subtle – you have to look for them but the story they tell is indelible. For more information, visit tourtalbot.org.