|

|

|

|

|

Interview With

Photographer/Environmentalist/

Author James Balog & Filmmaker Jeff Orlowski On the Evidence of Global Warming Beverly Cohn Entertainment Editor The Road to Hollywood

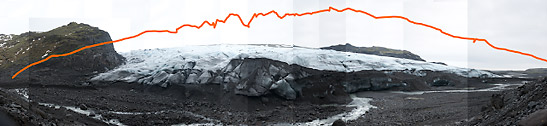

Filmmaker Jeff Orlowski founded Exposure, a film production company dedicated to producing socially relevant films. He initially worked with Mr. Balog on the EIS expedition, which eventually evolved into this most devastatingly beautiful chronicle of a planet headed for multiple environmental disasters. Balog and Orlowski recently sat down with a group of select journalists to discuss this topic and the following has been edited for content and continuity for print purposes. What motivated you make this spectacular film? Balog: I've been a great fan of Arctic and Alpine environments my whole adult life. I always thought they were incredibly wonderful, beautiful places, but then I became aware that the climate change story was manifested in the ice and a series of assignments in 2005 and 2006 brought me into those places and at the end of those assignments, I realized there was something here that required putting cameras out there to try to see what happens in the course of a short period of time and on a regular basis, instead of just going back once a year. So that's what motivated me. The camera technology you needed was not available. What happened when you approached the various manufacturers? Balog: They were really intrigued by this and I thought that the knowledge of how this thing could be engineered would really be straightforward. I was truly incredibly naïve about that and very quickly learned that the techies at these camera companies said probably it will work, but we don't really know. So, eventually it became a matter of just doing the experiment and finding out if it worked. It was nerve racking. If this had been a proper corporate science experiment, where a NASA-style, big science-funded project had been sending these cameras up to Mars, you'd spend five years doing R & D, but I felt the pressure of time. I knew the glaciers were receding and I wanted to get eyes on them quickly. Also, didn't have the financial capacity to be doing experiments for a year or two. I needed to get the cameras out there, make it happen, and hope for the best. Orlowski: To add to that, I think it's somewhat understated in the film the degree to which James literally designed and invented a new camera system that did not exist. He is not a technician, he is not an electronics guy, he hates that stuff, yet in spite of all of that, he did invent something new. Nothing existed that could have handled this task. How did the two of you initially hook up and how did the project unfold? Orlowski: We met through a mutual friend. I was familiar with James' work and was a big fan. When I learned that he was doing this trip to Iceland, my friend helped get me in the door. I volunteered to shoot video and that was my opportunity to work with him and get close to the project. Then he invited me to go to Greenland and Alaska and it kept rolling from there. But, we weren't making a film at first. I had no intention of making of a film at the beginning. James had been working for two years doing photography on the ice and then he had the idea of doing time lapses of the glaciers and knew that it would be a big undertaking and thought he should film it and document it - even if the video was just for promotional purposes.

Orlowski: The first year-and-a half I was just there to shoot videos and help with the cameras wherever I could and at that point, we had a couple hundred hours of footage and the time lapses were showing some very significant changes. It was then that I suggested that we make a movie.

The shots are amazing and obviously dangerous. What was your personal experience as that doesn't show on camera? Orlowski: There's something about the harsh weather that James experienced, I had to experience as well, so for me, it doesn't matter whether my story is part of the film in terms of those difficulties. We both went through all of those landscapes and those shooting conditions. This is a great chronicle of what we've done to the planet. Can this be turned into some kind of action? Balog: The easiest part of this work is going out in the field and it occupied a lot of our time and energy the first few years, but now we're in the education and outreach phase and telling the story. We will soon have an iPad Ap and we'll become expanded for educational purposes by the springtime. I've presented to President Obama's Energy and Climate Change staff on Capitol Hill and Jeff gave a screening and handed out DVDs to every senator and congressman's office and through various staff members, we have had a number of opportunities to put DVDs on President Obama's desk. Hopefully this will help them understand the evidence and the immediacy and reality of climate change. Orlowski: We didn't come into this as activists or environmentalists. We came to this as image-makers and storytellers and we saw the reality and the significance of this issue and felt a responsibility to do something about it. So we do screenings and people ask us what they can do. We don't have all those answers, but we're partnering with people and trying to get involved with political activism. The message I like to share is that nobody told James to do this. Nobody told him to go out there and install time-lapse cameras and spend five years risking his life to tell the story. What do you hope the film accomplishes? Orlowski: Where we see the film having an influence is by shifting perception. We don't have a problem with economics or policy. We know we have the tools and technology to solve this issue. We want to do something about it so if people can use the film as a tool to help motivate others to care and prioritize this as a real issue, then we will see some difference. Was there a time that you were frightened during this dangerous shoot? Balog: It was more of a sort of a grinding, never-ending fear and it would often be at its worst the last couple of days before I was leaving home. It was in the packing phase that I would get really deeply anxious that this might be the last time - that I would not come back and see my daughters and wife again and that was a really hard thing to travel with - to close the back packs, close the duffle bags, put them in the car, and get on an airplane. So with that fear, what drove you? Balog: It was my duty. It was my responsibility. It was my privilege as a creative artist and my burden as a human being - to be aware, to recognize that I was seeing this thing happen and I could not turn away from it. We've done a combination of art and science and the integration of those two modalities is a powerful way to illuminate and bring alive some of these scientific concerns.

Cameras are readily available to just about anyone, but what makes a National Geographic photographer such as yourself? Balog: You have to have passion and you have to have obsession and you have to have the ability to work incredibly hard. You also have to have the desire to look under the surface of reality and extend your vision further. It's all of those elements and in fact, a lot of people who work professionally may have all of those first characteristics, but don't necessarily have the drive to look under the surface of obvious appearances and inherited wisdom. What did you learn creatively from James? Orlowski: I learned that it's easy to make a beautiful

picture, but the difficult thing is to make a beautiful picture that

tells an important story and James figured it out. He came at

images almost backwards, coming up with the concept first. The idea

was there first and driven by the ideas and the greater theme, we then

figured out a way to represent that photographically. So, it's not just

coming up with an idea for a picture and trying to execute a specific

image.

The moment where you discovered the first round of cameras were not working was crushing. How did you get your second wind to keep moving forward after that terrible disappointment? Balog: The crushing thing about that moment was that a week later I was going on a big, expensive expedition to Greenland and I realized when I'm there at the camera in Alaska, I don't really know if those 12 cameras we're deploying in Greenland are going to work. I don't know if all the money we're spending on having five or six people out in the field will be money well spent. I'm idiot. I haven't tested these cameras enough and that's what the hard thing was, so it was a number of weeks of anxiety until we got out in the field in Greenland and started to discover, where the problem was coming from. It was a while before this sense of anxiety and uncertainty started to dissipate, but we knew we still had a lot of uncertainty and it was another year or so before everything settled down and we knew that everything was working fine. How did you raise the money for this project? Balog: There were no private donors in the beginning. I went to Nikon for sponsorship and they generously gave us 25 camera bodies and 45 lenses. Pelican, the manufacturers of those cases, gave us a whole truckload of cases. Mann Photo gave us all the tripod heads. National Geographic provided the bulk of the seed money that got us out the door and some of my academic collaborators had grants that were already in the pipeline from NASA in the National Science Foundation to do work in Greenland and Alaska so with all of those pieces put together, we had barely enough support to get out the door. I collected no salary the first year. Everybody got paid except me. So, it was pretty lean but eventually we started to get foundation support and a lot of private donors came on. I also spent a lot of personal cash the first couple of years to support this. My parents and brothers helped out. It was crazy. This was not a good business plan, but it was a way to get the thing done. How much financial support did you actually get from National Geographic? Balog: Over three years, National Geographic was in it for well into the six figures, but this project went well into the seven figures so as substantial as their support was, and as ambitious as it was, and as grateful as I am for it, it still was only a piece of the bigger pie. In the current media age of print media, that kind of money doesn't exist anywhere, but they were willing to do it, but the costs were so ridiculous, that it was even beyond their capacity.

Did you have several teams? Orlowski: At the beginning, we were really just one team - the four of us or in luxurious times, five or six people. That was probably the largest crew we ever had. Often, it was James, a third person, and me.

What's going on now with your project? Balog: As we sit here, we have 34 cameras on 16 glaciers including Nepal, Iceland, Greenland, Canada, Montana, and Alaska and I hope to expand into South America. How will you shift perceptions of those people who refuse to believe in climate warming? Balog: We'll keep beating on the doors, keep putting the story out there, keep telling the truth. I am idealistic enough to believe that the truth will eventually get assimilated into societal behavior. I'm sure it doesn't always happen that way, but I believe that, because this is the correct thing to be paying attention to, that we will eventually pay attention to it. There's a famous quote from Winston Churchill in 1940 or 1941 when Europe was already at war. The French and the English were trying to get us to enter that war and Churchill said that you can always count on the Americans to do the right thing, but only after they've exhausted all the other options. I believe that we will eventually do the right thing. I heard another quote this morning on TV, when I was working out in the gym. I'm paraphrasing, but Lincoln said that just because the probability is that you might fail at a task, it doesn't mean that you shouldn't try it, so I think that's the basic challenge in front of us. We should try it anyway and I think we are going to win. We know how the David and Goliath story turned out. David eventually wins. It may not be easy and it may be a high-risk thing, but I believe, because this is such a real and imminent danger, that this issue will prevail over skepticism. For those skeptics, what are the advantages of dealing with this problem? Balo: It's good for the country. If we deal with climate change, we create new industries. We create new job possibilities, we create a healthier air supply for us to breathe, and we can stabilize some of the geopolitical risks that are inherent in this. There's lots of positives that come from addressing the excess burning of fossil fuels and treating that beautiful cerulean air supply out there as a garbage dump, which is what we've been doing. We consider that to be a place, where for free, we can throw our refuse. We've been doing that for four million years since Homo Sapiens came down out of the world of the chimpanzees. We can't afford to do that anymore.

Do you feel optimistic that the planet will take action? Balog: I can be depressed about this almost on a daily basis and for the sake of my sanity, and for the sake of my belief in my daughters' futures, I can't let myself go there. I've got a 24-year-old and an 11-year-old and want to offer them, in my own individual, solitary way, a better world and just refuse to fall into cynicism and despair. Orlowski: I've been getting more and more optimistic over the last couple of weeks. Because of events like Sandy, climate change has become more and more of an issue. People are talking about it again and in the president's acceptance speech, he acknowledged it. I think we have to address the consequences of climate change. There is no way to avoid it and it's just a matter of when it happens and it's a matter of how bad the damage will be until that point. Balog: We're all thinking Hurricane Sandy but it's important to recognize that the current issue, in terms of the earth's system overall, is that the pattern of extreme, violent events was predicted and recognized by the climate scientists decades ago. They were predicting that we're going to see more extreme precipitation, whether it's snow or rain, more violent storms, more droughts, more wild fire seasons that will be much more intense because the droughts make wild fires more possible. All of that is coming to pass and that's what is amazing to me. Damage has already happened. Climate is changing. We're seeing the consequences and getting whacked in a big way with disasters, forest fires, floods, tornadoes, and hurricanes and there are major, multi-billion dollar expenses connected with this. The idea carbon in the atmosphere would warm the air was put forward at the end of the 19th Century for God's sake. This is not cutting edge stuff that some guy in an atomic physics lab in Berkeley just invented. This is over 100 years old. How is climate change manifesting in the rest of the world? Orlowski: There are island nations that have announced that they have to relocate their entire population of 100,000 people because they know they're going under water. We know that hundreds of millions of people will have to relocate as a result of flooding homelands and we don't need three feet of actual sea level rise to impact three feet of the coastline. We know just a couple of inches can have a huge impact because the storms are getting bigger.

Is the damage reversible? Balog: It's going to be a long process to pull it back to stabilize it and we won't see the benefits of right action now for many decades in the future, but I think we could get many positive effects right now that will have even more positive effects in the future and a more positive environment. Not taking positive action, at a minimum, is selfish, immoral, and unethical and to the people of the future, it may actually appear to be criminal behavior. What could we, as individual, do starting today? Orlowski: Unfortunately, there's only so much an individual person can do. The big stuff has to happen from the governmental level and needs to happen on a very large scale, and we need to have regulations on how we burn fossil fuel. The public can use their voice to try to influence that and that change is going to happen either by the public demanding it, or when certain leadership recognizes that they have a responsibility to protect the public from evil they might not even know about. Can you cite historic morality references? Balog: Back in the early 19th Century, right up until 1861, people were saying we can't stop the industry of slavery. Slaves were machines for manufacturing goods. That's how it worked and there was a big sector of the country that was saying we can't stop, you're going to destroy us and they were willing to go to war over that. But, stopping slavery was the right thing to do. It was the ethical and moral position and I don't think any rational person would see it otherwise. Orlowski: People of the future will look back at our use of fossil fuels the same way we look back at slavery. It's a moral issue and we're at the point right now. Balog: You know 100 years ago, ten-year-old kids worked in coal mines and textile factories and that was thought to be normal and necessary economic behavior. People argued like crazy about that. Up until I think 1928, women weren't allowed to vote. These were fundamental principles of the societies at that time. Women can't vote. Kids can be used in labor. Slaves should be employed for economic value, but eventually you look back on it and think what was wrong with those people. Were they crazy?

Orlowski: It's a shame that this issue has become politicized - that it's become this Left vs. Right. We don't care what your political stance is. We don't care what your views on the environment are. We know that climate change will have an impact on future generations and it's a shame that it's been turned into a political football. I believe, deeply, that this is an opportunity right now for people who have been in that skeptic camp to stand up and say ok, I recognize what's going on with the science and I'm going to stick my neck out and go on the trajectory of where the future is going and say this is something we need to fight for - this is something that I recognize is a real concern and those people are going to be looked at as the heroes. There's an opportunity right now for the Republican leadership to be the heroes that the future will look back on. Editor' Note: "Chasing Ice" is on screen at Laemmle's

Monica 4 in Santa Monica, Sundance Sunset 5 in West Hollywood, Laemmle

theaters in Pasadena and Encino, the Nuart and The Landmark in West

LA. Check your local paper for screening times. |

This site is designed and maintained by WYNK Marketing. Send all technical issues to: support@wynkmarketing.com

|