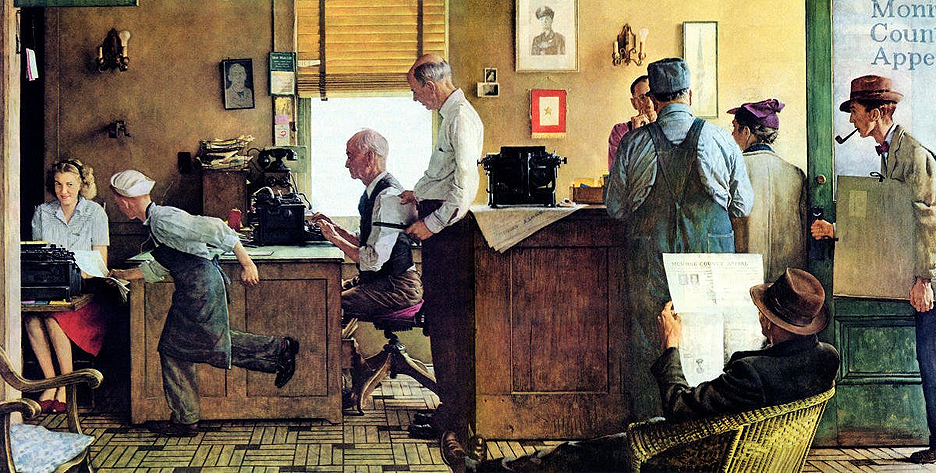

Skip Kaltenheuser, a hard-bitten scribe if ever there was one, reflects on the state of the US media from the comforting environs of the National Press Club in the heart of Washington DC.

One reason I joined the National Press Club in 1995 was that on various occasions before Hong Kong’s handover I’d darkened the door of the FCC. I hoped that the NPC’s substantial oblong bar might be cousin to the FCC’s main bar with diverse central casting characters including criminal barristers of the

Rumpole flavour, cargo shippers, pilots, politicians and others seeking what was in the wind as journalists’ tongues loosened, and vice versa.

Though the NPC I joined wasn’t quite as colorful as lingering old-timers described, it still offered intrigues and camaraderie. In The Reliable Source Bar & Grill, a plaque pays tribute to John Prokoff, a bartender before my time whose bone-dry quips included “Let’s get drunk and be somebody” and “Do you want separate glasses?” I did know the late barkeep John Kulawski. Whenever my young kids joined me, they left enriched with coins John fetched from their ears. John, gruff but erudite, turned the bar into a

continuing education.

The club occupies the top two floors of the 14-storey National Press Building in the epicentre of the US capital. When built in 1927 it was Washington’s largest private office building. The club once owned the whole place but lost it after a mismanagement scandal many years ago amid a major renovation. From the club windows one can glimpse the White House over the top of the US Treasury Department. Across the street is the Willard Hotel, to which President Ulysses S Grant, fleeing presidential pressures, strolled for drinks or a meal in the lobby, where he was bedeviled by favor-seekers. Hence, “lobbyist.”

Plenty of lobbyists, with their cousins in public/media relations, haunt the NPC nowadays, a large swathe of the membership. Their higher dues, and the tables they buy out when bosses or clients or officials they’d like to influence address the club as ballroom luncheon speakers, help pay the freight. Speaker line-ups seem to trend more per establishment than when I joined and participated.

Burgers and Bangers

Bangers and mash is not on the bar’s menu. I’ll suggest it when I run into the club’s incoming executive director, Didier Saugy. Previously, we did have the Alferd Packer Burger, named for a cannibal who was the lone survivor of six prospectors trapped by Colorado’s brutal 1873-74 winter. I don’t mean to make too much of this, but Alferd is no longer on the menu, having been replaced by the more homogenised Angus. The loss of Alferd in one’s gullet seems a bellwether for trends impacting the NPC and journalism generally.

Lately, I’ve viewed journalism through the prism of the activist Julian Assange – a media Rorschach test. Many Washingtonians, including journalists, are surprised to hear that Assange has languished for four years in solitary in Belmarsh Prison in London, following seven years of confining asylum in Ecuador’s embassy there. Nils Melzer, former UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, says the treatment of Assange, who is on the autism spectrum, amounts to straightforward torture.

While he was in the Ecuadorean embassy, US intelligence minions spied on Assange, his family, friends and lawyers, and visiting journalists. Mike Pompeo, Koch Industries’ man in Washington who went from Congress representing my home state of Kansas to becoming CIA Director and then Trump’s Secretary of State (and until recently a presidential aspirant), plotted to kidnap or assassinate Assange after Wikileaks revealed the CIA’s goals of controlling people’s smart TVs, browsers, phones and cars. Orwell, anyone?

The Biden Administration’s Department of Justice has continued the Trump Administration’s quest to extradite and prosecute Assange under the 1917 Espionage Act, which was designed to target German operatives during World War I, with a side job of quashing dissent. This is the first time it’s been trained on a journalist or publisher, let alone an Australian who wasn’t even in the US. This prosecution is perilous to domestic and foreign journalists everywhere. Hypocrisy blows Biden’s credibility on press freedom off the moral high ground, which authoritarians eagerly note. For more detail, search “Belmarsh Tribunals”.

Venerable Dan Ellsberg, who during the Vietnam War stunned the world by leaking the Pentagon Papers, told me that prosecuting Assange is the US government’s plan for introducing a UK-style Official Secrets Act, under which journalists could be prosecuted for simply receiving classified information. James Goodale, who ably defended The New York Times in that case, told me the same. It would quash journalists’ attempts to reveal the truth.

Envy and Resentment?

It seems to me that many journalists nowadays can’t identify with this concern. Most will never break a story of that sort, never depend on whistle-blowers that the government seeks to crush. Envy? Resentment? Perhaps. Meanwhile, there’s no end of over-classification by officials to muddy transparency and avoid accountability.

So are there constant drumbeats on mainstream editorial pages and elsewhere? No. On Assange, the NPC – a frequent commenter on foreign oppression of the press – keeps its head insistently sanded. Having pushed the club on this matter for years, I’ve usually encountered a cone of silence. I’ve heard comments from those who should know better such as “What if Assange is a Russian spy?”, or falsehoods repeated with certainty like an unredacted document dump.

Often, the fanciful assertion that Assange isn’t a journalist is trundled out, never mind his stunning record of journalism awards. Brilliantly, Wikileaks enabled his revelations via technical innovations including an electronic dropbox to obtain information anonymously, which is then vetted. My definition of a journalist is simple: anyone who truthfully informs the public of matters impacting their lives. Wikileaks never had to retract anything as untrue.

Caustic attitudes pay testimony to successful propaganda vilifying Assange. It ramped up in 2010 when I saw Assange step into the cross-hairs of fame at a news conference in the club. He presented the shocking Collateral Murder Tape. A helicopter snuff film of a dozen or so Iraqi civilians, including two Reuters employees and a Good Samaritan ad hoc ambulance driver, whose kids were in tow, with a chilling soundtrack by gleeful pilots. It crystallised government lies on war crimes and the conduct of the Forever Wars. Nobody responsible for the attack or the cover-up has been prosecuted.

Political propaganda poured with perpetuity when Wikileaks published (true) emails revealing that Hillary Clinton spoke out of both sides of her mouth regarding Wall Street benefactors, and that the Democratic National Committee undermined democracy, rigging the 2016 primaries against Bernie Sanders.

Some information gatekeepers have judged public enlightenment non-newsworthy if not in service of a higher purpose: say, the election of Hillary. And while avoiding criticism of favoured administrations or political parties, many in journalism otherwise cheer them like high school football teams. Some seem to be self-appointed auxiliary spokespeople for government, aka stenographers. Assange is emblematic of what the mainstream downplays or ignores to avoid roughing up pet political and media narratives.

Assange is bad for business. The Forever Wars confirmed Washington as a company town for the military-industrial complex that President Dwight Eisenhower warned of back in 1960. That influence cannot be overstated, including the weapons advertising largesse that many publications enjoy. It’s the same when it comes to media ownership. For example Jeff Bezos, of Amazon notoriety and owner of The Washington Post, is in hot pursuit of government contracts to manage clouds for intelligence and military agencies.

As the NPC emerges from a long, costly pandemic coma, public trust in media scrapes the shoals. Journalism sinks amid collapsed business models and layoffs. Understandably insecure journalists eye laterals, perhaps PR in arenas that they report on. Many now interpreting the world for us were children or teens during the invasion of Iraq. Most weren’t born until after the Vietnam War. Institutional memory is shot. We’re all cannibals now.

As I write this in May, steadfast NPC obtuseness on Assange remains. Perhaps by publication date that might change. It would be a pleasant, if astonishing surprise.

(This essay first appeared in the July issue of The Correspondent, the quarterly put out by the Hong Kong Foreign Correspondents’ Club)

(Note, bangers and mash is a HKFCC staple sustaining many scribes, Didier is the former manager of the HKFCC and new exec. dir. at the NPC, hence the reference).