The low lying banana boat picks up a passenger arriving from the airport and departs the small dock with the caution not to dangle a hand in the water. The reason soon becomes apparent, the eyes and rough hide of a ten foot crocodile surfaces several feet off the boat, then disappears in murky waters of the mighty, 3,540 km long Zambezi. An hour later it enters a wide stretch known as Atuleo Amanzi, or Quiet Waters, where David Livingstone first drifted by in 1855 before discovering Victoria Falls 18 km down river – luckily not by going over it, as he would have dropped more than his jaw at the sight of the mile wide river plunging 360 feet. Think of Johnny Weismueller’s Tarzan rescuing Boy as he napped toward certain doom on an breakaway lily pad.

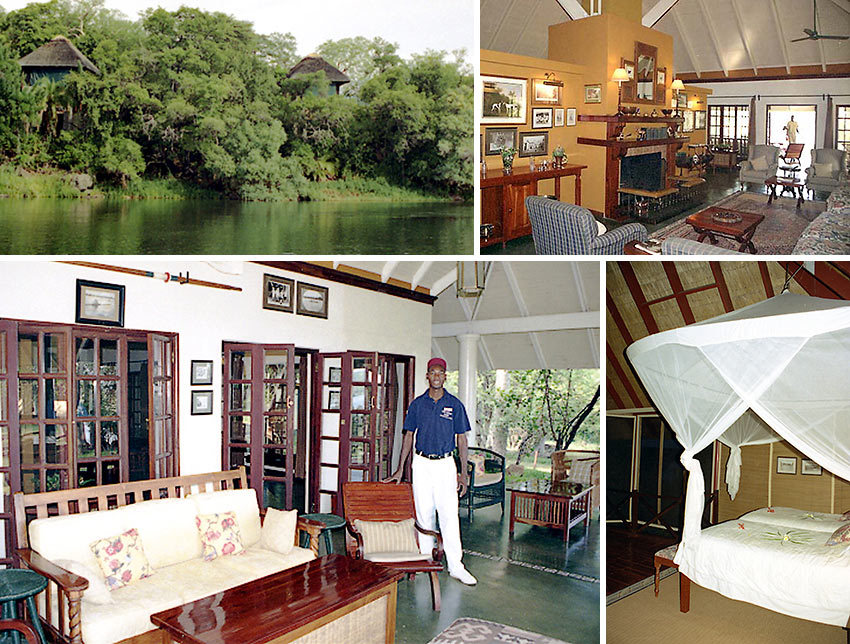

Curious hippos surface about the boat, which moves quickly to safer waters. High among the thick trees along the river bluff, portions of several bungalows can be seen on the Zambian side, facing Zimbabwe National Park and sunset. The boat docks and under the trees steep steps lead to the River Club and to the style to which I’d like to become accustomed but probably won’t.

Ten thatched chalets, accommodating up to twenty guests, with balconies hanging over the river on stilts, their backside open to the river. A swank bedroom on the top level, where draped mosquito netting becomes an art form framing an orchid presentation on the bed. An old-fashioned tub and shower are on the lower split level, allowing a naked wave to passing fisherman angling for Tiger Fish. The front door opens toward a bird bath, a croquet lawn and an Edwardian home that is the hotel’s dining room and verandah, with a library and drawing room that looks transported from an English fox hunt and where enough post dinner port has flowed to float Boy’s lily pad.

This particular night, at his private home on the river bluff, secluded away from the hotel down a long nature walk path, the hotel’s proprietor is entertaining River Club guests, who sit on makeshift bleachers. The special occasion is a rugby championship, brought in by a satellite TV with mercurial reception, cursed by the owner as he fiddles with wires and paces like a panther, that heightened game suspense. Guests catch the owner’s enthusiasm as he redefines irrational exuberance every time England scores over Australia, and his hounds take up the howl. The River Club chef, an Australian, is as combative until England emerges victorious. He is needled by his boss so mercilessly that guests wonder if a food taster would be a good idea at that night’s dinner on the veranda, where everyone breaks bread together and spin stories of the day’s adventures.

Most guests tonight are from the UK, and welcome rugby’s flash of Empire. The game, and the relative comfort offered by the club, underscore the duality of African travel, the upper crust exclusivity stands in high contrast to the often elemental existence in much of Africa, which depends heavily on the tourism the high end travelers set the gold standard for. They depend on the wildness of Africa for many of the adventures they seek, for the feel of being someplace truly different. A premium is given the timeless quality offered by areas and wildlife that much of Africa struggles to keep in their natural state.

The hotel often boards travelers acclimating to Africa after arriving in the region, for which most initially fly into South Africa, or decompressing from a package of safari trips elsewhere in the region, from Namibia’s Skeleton Coast to Botswana’s Okavango Delta, usually traveling by small plane.

But there are plenty of local attractions to choose from. Victoria Falls, known to the local Kololo people as Mosi-oa-Tunya, or the Smoke Which Thunders, is perhaps the best known destination in Africa. Not far away, one enterprise offers day long elephant safaris, where travelers ride double with guides on elephants through a private preserve with ample wildlife, big cats excepted. There are rhino tours into the Livingstone Zoological Park, and other safari options, including in Zimbabwe across the river. The club’s pontoon boat provides sunrise and sunset river trips, or guests can take canoes. Chilling out at the hotel includes croquet, lawn tennis, fishing and birding.

Local artisans are among the best on the continent, and the outdoors crafts market at Victoria Falls has terrific offerings. Historical Livingstone, the Livingstone Museum and the railway museum offer interesting glimpses into the colonial past. The River Club can make arrangements to stone age sites in the region.

But one of the most thought provoking offerings is in a Zambian village which Peter Jones, creator and owner of the River Club, has committed to helping with its challenges. Jones, a former British commando officer in the 5th Airborne Brigade and a Falklands veteran, was schooled not just in rough and tumble special operations but in the importance of winning local hearts and minds. “Here in Africa,” says Jones, “we are always keen to see that the people see direct benefits to themselves as a result of our decision to invest in the continent.”

The River Club seems an odd focal point for community development of an impoverished village. The swank main building is the former home of “a delightful elderly Belgian lady” who wanted to start a lodge operation but didn’t have proper financing, and was Jones’s home for two years after he bought the place in 1995. The scene is worlds apart from the 3,000 inhabitants of Simonga Village where children play amid humble huts, nervous chickens, and parched plantings of millet, mealy and beans their families consume or barter.

But Jones treats his small empire as a command center in tackling the challenge of improving the quality of life at Simonga, mindful of entreaties from the local Environmental Impact Assessor to “Please make sure that you are able to keep it going. The people have sadly become used to others letting them down.” After four years of operations, Jones determined that his company was on a good enough footing to take on the responsibility.

The villagers are mostly of the royal tribe of Zambia, the Lozi, whose King, the Litunga, once ruled over the whole of what is now the Western province. A quarter of River Club staff are Simonga villagers Jones has trained.

The first objective, says Jones, was to create incentives for receiving visitors – a compensation formula based on the number of guests touring the village. We already pay a unit per guest for the removal of litter and other debris from the tour path. We’re now asking the villagers to devise a rubbish collection system for the entire village, offering to haul away debris in our vehicle. Compensation will increase with the completion of a palace for the chief to stay when meeting with his local subjects, and when the village trains its own guides to conduct tours.

“Assessing critical village needs,” says Jones, “we quickly realized the need to focus efforts on the children. Education is the most important feature of any society, for it ensures growth. The school project has gone well, and we have raised enough money to put all the kids through school for at least one year. We have been able to buy books and pencils for all the children. Recently, an American guest sent a load of educational books.” Jones is exploring small solar technologies that would provide light for extra teaching and homework time, and is laying plans to add classrooms.

One guest, who wishes anonymity, agreed to sponsor the top child in the school for four years of education at the town’s best boarding school, a commitment of US$8,000. An American who lives in Switzerland, he also donated three football strips and 10 footballs for the sports teams through his Lions group in Germany, says Jones. “Six foot seven inches tall, he sends his hand me-down clothes to the tallest man, who had been out of luck finding a suitable wardrobe in town!”

Jones hopes to leverage his efforts with similar considerations, large and small, from interested guests who recognize the village’s difficulties. One example he cites is “the Street family, from New York. They brought their son, Evan, and their three daughters. We organized a football match at the school for them to take part in. Afterwards, Evan handed over a donation of US$500 he had raised as part of his Bar Mitzvah celebration. It was a terrific time, and a wonderful example for the village youngsters.” The money purchased books, pencils, locks for the cupboards, chalks, dusters, rulers and other essential items often taken for granted.

One connection between River Club patrons and Simonga villagers began with Jones’s discovery of a skinny young boy on a blanket in a hut. At the time he was unable to speak and suffered from the loss of parents – his father in prison for killing the boy’s mother – as well as from cerebral palsy. Taken to the River Club, Mapulanga was fed, given clothes, and placed upright in a chair while he sipped his first orange juice. A couple days later Keith Ruff, from Coralville, Iowa, and his daughter Kelly Armstrong, were staying at the lodge and, hearing of the boy, asked to be introduced. Keith also has cerebral palsy and is a counselor for others with the affliction. Keith allowed Mapulanga to spend time in his wheelchair.

The Adamson’s, a visiting English family that lives in Belgium, decided to purchase a wheel chair for Mapulanga. Jones was in touch with a local organization that supported handicapped children, and they knew of wheel chairs being make in the capital city of Lusaka, 300 miles away. Measurements were taken, six weeks later the chariot arrived, and Mapulanga’s first words were “Tweende” – “Let’s go” in the Lozi language – as a cousin pushed him to a shop to buy biscuits and sweets. Sadly, Mapulanga’s hope of attending the University of Zambia will not come true, as he recently passed away. But until his death he was thrilled to attend Simonga school. His life was greatly brightened by the dreams that before never seemed possible, inspiring his village as well.

A major challenge is the water supply, for which women have had to spend most of the day walking to the river and schlepping large jugs back, returning exhausted and short on time for family. Hippos are feared by fishermen, but the Zambezi crocodiles are notorious for dining out on people who linger at the river’s edge. Crocs take one or more Simonga villagers a year.

“We have dug three wells with another three in progress, aiming for everyone to have good, clean water within 500 meters of their homes within a year,” says Jones. “Hand pumps are being procured from a donor group, and we hope to resurrect the old borehole pump.” This is a critical step in allowing the village to grow more crops during an unusually long drought building what observers call “the perfect famine” striking the region.

Other factors mugging Zambia, the government of which logged significant social and economic progress during prosperous times, are an economic power dive, including fractured copper prices; difficult adjustments to the competition that accompanies globalization and the imports of cheap used clothing that have devastated Zambia’s textile industry; the demagogic destruction of agriculture infrastructure in the region’s former breadbasket, neighboring Zimbabwe, by its fallen angel dictator, Robert Mugabe.

Floating down a quiet portion of the often roaring Zambezi River, on the Zambian river banks across from Zimbabwe one can see new lodges and other enterprises popping up, established by farmers who fled the disastrous reign of Mugabe. His “land indigenisation” scheme aims to replace 4000 of Zimbabwe’s commercial farmers with untrained settlers – as well as, critics claim, Mugabe favorites such as the wife of the army chief and the Zimbabwe ambassador to the UN. In Zimbabwe, commercial farmers who farm now face incarceration, never mind the million and a half people they employed, many of them also seeking refuge in surrounding nations. The barometer of economic desperation is readily read in the faces of those selling Zimbabwe’s impressive crafts at Victoria Falls markets.

And then there is H.I.V. AIDS experts now predict that, absent significant developments, the disease may eventually claim half the adult population of Zambia. In a country of 10.3 million people, two million AIDS orphans are expected by the decade’s end. Already, 650,000 children have lost one or both parents. The millions at risk of malnutrition and starvation, in part from the agricultural disaster in Zimbabwe, regional droughts and incomprehensible policies refusing food aid such as genetically modified corn, will face increasing health vulnerability to AIDS, as well as to other diseases that devastate the region.

The traditional Zambian village reverence for raising children, which awarded special status and care to orphans, is being overwhelmed as grandparents wear out, says Jones. The spectre haunts him as he encourages a group of Swedish doctors, one a former guest, to explore setting up satellite clinics in nearby villages that share a visiting doctor who will help relieve local nurses. “Even the simple addition of toilets and related sanitation programs, with health education, would improve everyone’s life tremendously,” says Jones. “Environmental maintenance is quite a challenge, and the women are quicker to understand its importance.”

Along the gauntlets Jones must run are petty bureaucrats “who see investors as a money wells from which large amounts of cash can be extracted”, while providing very limited municipal services.

“For some efforts, the village has been slow on the uptake but now they see that we have done what we said we would,” says Jones. “Now we will promise to do something if they do something first. That incentive always holds promise, the belief that they can help themselves.”

Travelers seeking to personally connect with a facet of Africa should wander through Simonga, perhaps puzzling out approaches, micro and macro, to the daunting challenges faced by much of Africa.

Antics for the Frantic:

Victoria Falls offers a carnival of thrill rides across an exotic amusement park without borders. Pursuits offering high octane adrenaline include arguably the world’s premiere whitewater rafting, boogie boarding through rapids and waves, microlight flights, and bungee jumping off the 1905 bridge, an engineering marvel built for moving trains over the vast river gorge between Zambia and Zimbabwe, 111 metres over the river.

This writer took Jone’s dare to take on the legendary class five rapids of the Zambezi, on a day trip organized by Shearwater Adventure. The British Canoe Union ranks the river grade 5, “extremely difficult, long and violent rapids, steep gradients, big drops and pressure areas.” The distance between rapids varies from 100 metres to to 2 kms. The river let me know where I stood with it, my eight person raft was flipped. Failing to reorganize ourselves out of chaos and climb the upended raft, we balled ourselves up and shot along through a stretch of rapids several blocks long, thankful for helmets and life jackets and the avoidance of rapids by hippos and large crocs. One rapid in the day trip, (trips range from half day to five days) “Commercial Suicide,” is unnavigable and must be portaged, though one impressive kayaker familiar with the river tackled it, disappearing and then popping up further down river.

The day trip offers approximately fifteen significant stretches of rapids, mostly class five. There is a good orientation and training session, and the guides are experienced. Waterproof cameras only, or kiss your camera good bye. The guide in my boat was excellent and amiable, it was sad to see his sinewy body with the lesions that are markers of AIDS.

Every bend in the river brings new views of the impressive gorge, which is 400 feet deep at the put-in point, and 750 feet, a taxing hike, at the take out point. The river drops 400 feet over the 24 km in the one day trip, and can be as deep as 200 feet.

Not yet content to leave well enough alone, rushing to the Zimbabwe airport, I made a quick detour to a section of gorge with several thrill options backdropped by a bend of the Zambezi. The one that captivated me was the Zambezi Swing, 53 meters of unfettered free fall down a sheer cliff. When a line attached halfway across another line that stretches across a deep, wide canyon reaches its length, it whips the person from free fall into a long, fast pendulum swing across the boulders and tree tops swinging back and forth several times before the person is lowered to the floor, for a steep hike back to the rim.

The fellow who was going to demo it for me backed to the edge of the launch platform, stood there for a couple minutes, started trembling and stepped back, slipping out of his harness. “Too much time working on the edge,” explained the proprietor, a South Africa lawyer who sought a new challenge. Before I could think about it, he had me in the harness, my heels over the edge, my hands tightly around the line so it didn’t jerk me into the cast of “The Sopranos,” Vienna Boys Choir version. Tethered to a tree, he holds my arm, slowly leans me backwards, gives a Cheshire Cat grin and says “Three. Two. One…Bye!”

Postscript: This offering is part of an occasional series of favorite travels, pursuits and places fetched from the Wayback Machine, of experiences I’d like to return to for another perspective. Hence, some aspects might be a bit disjointed from the present as time moves along. But enough remains accurate to provide a sense of place to those interested in exploring the environs. Apologies for the photos not quite hitting the mark. They came from a primitive drugstore scan of snaps taken from somewhat damp film after the camera, despite being tightly wrapped in plastic, was fire-hosed when a raft was flipped end over end in the middle of a three block long stretch of rapids. Next time, a waterproof camera only. For further information, visit The River Club.

Growing up in Kansas, Skip Kaltenheuser was tuned to travel by a traveling salesman father’s pedal to the metal vacations. He extended his reach with travel writing, and efforts such as supervising elections and doing special projects. When they’re willing to slum with him, Skip’s favorite travels are still with one or both kids, now young adults, neither indicted despite living in Washington, DC their entire lives.

Growing up in Kansas, Skip Kaltenheuser was tuned to travel by a traveling salesman father’s pedal to the metal vacations. He extended his reach with travel writing, and efforts such as supervising elections and doing special projects. When they’re willing to slum with him, Skip’s favorite travels are still with one or both kids, now young adults, neither indicted despite living in Washington, DC their entire lives.