Story and photographs by Gary Singh

In Trieste, Italy, at the northern fringe of the Adriatic Sea, I am experiencing what Jan Morris called “Triesticity.” Outside Caffè San Marco, we sit at a square table on a pedestrian street, Via Donizetti, that runs alongside the cafe. The Greek-Italian proprietor, Alex Delithanassis, is smoking a Chesterfield. The French rabbi from the historic synagogue next door, Alexander Meloni, is smoking Marlboro Golds. Caffè San Marco opened in January of 1914, when Trieste was still the main seaport of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Members of the synagogue have found refuge in San Marco ever since.

Delithanassis is Greek Orthodox, but since his daughter attends the Jewish school of Trieste, which is now open to anyone, he regularly hangs out with the Jewish community. And being Orthodox, he’s friends with the Serb Orthodox community, many of whom were refugees from the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s. There is no other place on earth where the aforementioned dynamics would unfold. Triesticity.

Austria-Hungary controlled Trieste for a few hundred years, that is, before the 20th century and the era of zoological nationalism then reconfigured the area multiple times, taking the city through numerous flags and border changes. After the First World War, Trieste officially became part of Italy. During the Second World War, the Nazis occupied Trieste for a few years and then Tito’s Partisans took over for forty days. Following the Second World War, Trieste became a free independent territory administered in two different zones, one under American and British control, the other operated by Yugoslavia. Then in 1954 those two zones were split, with the northern zone returning to Italy, resulting in the present-day city of Trieste, but with the surrounding area, the coastal lands and the frontiers all going to Tito. When Yugoslavia dissolved decades later, that second zone was subsequently split up again, with portions going to Slovenia and Croatia.

As a result, the majority of Trieste residents these days are native Italian speakers, but in a place where Italian, Germanic and Slavic influence and language all bleed into each other. The geographic borders make no sense to anyone. You meet Italian nationals with Germanic surnames and vice-versa. You meet Slavs whose mother tongue is Italian. You meet Slovenes convinced Trieste belongs to them. Some people even act nostalgic for Austria, people who were never even Austrian in the first place. A tiny percentage even argues to bring back the free independent Trieste.

Nearly every major thoroughfare in Trieste was formerly named something else—the signs were there to prove it—and the city seems to operate outside the linear passage of history, in regards to the ways cities are normally defined by languages, allegiances or relationships to larger regions.

“In Trieste, calling yourself ‘Italian’ is always an individual decision,” one person told me. “Because we’re all mixed.”

Over the course of a few days, I relayed that comment to several other people. All of them agreed.

With such a gorgeous flavor of irreducibility, Trieste feels like a place where a transnational identity—on the level of the city and the individual—becomes normalized, not marginalized or exoticized. You can see it in the architecture, hear it on the streets, taste it in the restaurants or read it in the literature.

Yet the worn-out terminology often used everywhere else—words like, ‘multicultural,’ ‘melting pot,’ ‘tapestry,’ or even ‘mosaic’—all seem irritatingly simplistic when applied to Trieste. In the research I did before my trip, the best term I came across was by the local literary critic Bobi Bazlen who referred to Trieste as a cassa di risonanza—a resonating chamber—where all sorts of opposites co-existed in harmonic interplay, internally and externally. He was referring to the turn of the century, but the term exemplified how I already experienced the world as a harmonization of opposing forces. Far as I was concerned, the term still applied.

Above all else, the city proved the sheer nonsense of categorizing people according to nation states or borders. It seemed like everyone’s identity was formerly a part of some other identity, none of which was reducible to anything “pure.” Many locals I met had a legitimate disregard for absolutist categories. I loved it. Anyone who remained attached to a fixed identity was destined to suffer, as the Buddha said. Nothing was permanent, especially in Trieste.

Yet rather than dwell on the melancholic aspects of such a predicament, in Trieste it became a wondrous condition, allowing anyone to become a traveler, a person whose very nature impelled him or her to cross some sort of categorical boundary, or border, just for the sake of crossing a border.

Well-known Trieste writer and decades-long Caffè San Marco regular Claudio Magris referred to such a condition as confine dentro—the border within. In the introduction to an anthology of his travel writings, Magris wrote: “There is no journey without crossing borders—political, linguistic, social, cultural, psychological, even the invisible lines that separate neighborhoods in the same city, the barriers between people, the twists and turns that in our inner recesses obstruct our own way.” Only a writer from Trieste would have said it that way.

Magris carried on a long tradition of scribes at Caffè San Marco. During the cafe’s initial incarnations, every literary troublemaker showed up. The novelist Italo Svevo. The poet Umberto Saba. Students, journalists and intellectuals of all flavors. Magris was now in his eighties and had his own table.

“It’s that one right over there,” said Delithanassis, pointing to a large rectangular marble slab in the corner. “He’d sit there for hours.”

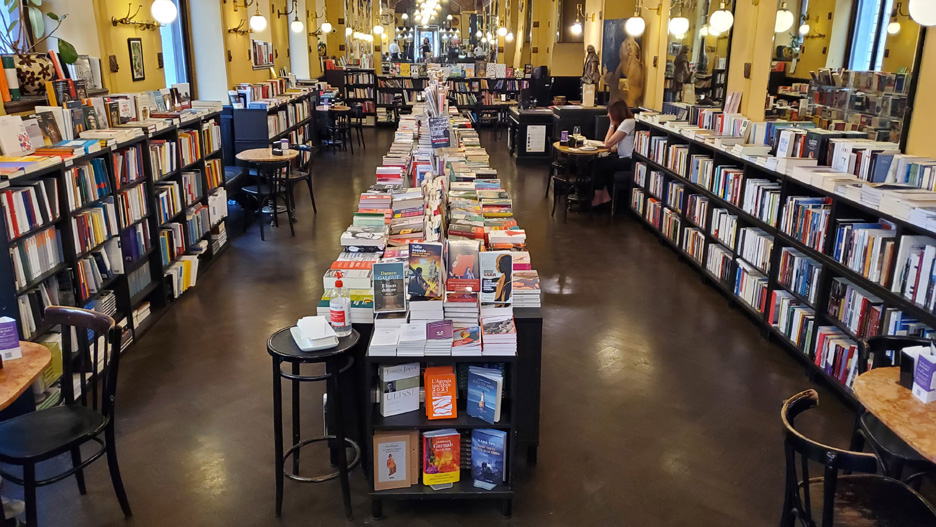

As a result, I wanted to move into this ancient coffee shop and pay homage to the giants of literature, the famous writers who once called Trieste home, so there I was, revisiting Caffè San Marco. It felt like a pilgrimage, albeit a secular one.

To be sure, throughout the world one found cafes that banked themselves on past writers who frequented their tables. Everyone wanted to visit an iconic hangout to sip an espresso where their heroes once did. That much was not unique.

But Caffè San Marco was different. Much of the interior remained from when it first opened in January of 1914, five months before the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and the beginning of World War One.

In a less volatile part of the world, a cafe opening at that time would not seem so significant. Yet even as Trieste was the third largest city in the Austro-Hungarian empire after Vienna and Prague, Italian irredentism was percolating out loud.

As Delithanassis showed me around, he pointed out examples of Venetian empire symbolism hidden in the décor of the place. The marble tables, all original, featured cast iron legs with lion’s paws at the bottom—the Lions of San Marco, the symbol of Venice. In those days, the lions also symbolized anti-Austrian sentiment. It was like a secret code for Italian irredentism, the movement to unify all Italian-speaking territory. When original owner Marco Lovrinovich, an irredentist, opened the café, everyone understood the dual meaning of the name.

As we sat at one of the marble tables, Delithanassis pointed out the bronze-colored stuccos on the walls, which were also original, although when the San Marco first opened they were brazenly tricolor. Lovrinovich had hired another irredentist, Napoleon Cozzi, to give the San Marco an Italian style décor.

I continued to look around. Ornate frescoes, old-world mirrors and historical photos of the original cafe hung on the walls throughout the establishment. The booths and chairs were darker than the darkest espresso. A multiple-tiered tray on the bar was filled with oranges. The same tray could be seen in a historic photo from 100 years earlier.

Delithanassis was a busy person. He jumped up and down to deal with employees, event planners or even just to slip outside for another Chesterfield, but he always came back to answer my questions. He then brought over a well-used shop copy of Stelio Vinci’s book on the 2014 San Marco centenary and plopped it down on the marble table. Caffè San Marco – Un secolo di storia e cultura a Trieste 1914-2014 included 150 pages of stories and classic photographsThere was not yet an English translation, but Delithanassis hoped that someday it could happen.

The history was indeed a star-studded affair. When the Great War erupted, Caffè San Marco was home to a secret passport forging operation for any anti-Austrian patriot trying to escape into Italy, so the cafe soon became the gathering place for Italian irredentist youths and young Jewish people from the synagogue, who were sometimes just as marginalized in Austria-Hungary as the Italian irredentists, although there was some overlap.

As a result, Austro-Hungarian troops destroyed the place and shut it down, although the fire department was able to save most of the inside. The cafe remained unused for several years until it reopened after the war, eventually passing through several ownership groups including a 50-year run under the proprietorship of the Stock family. Magris himself was then one of the prime movers who helped rescue San Marco from uncertainty when it briefly closed in 2012, writing a passionate newspaper editorial in support of saving the place.

In the opening chapter of his 1997 book, Microcosms, Magris furnished a masterwork of essayistic prose about Caffè San Marco, not only depicting the matrix of characters therein, of which he mentioned more than once the itinerant scholar type who accosted decades-long regulars with the same dumb questions about Trieste—exactly as I would have done had I discovered him sitting there—but also supplying slices of history that helped inspire later books, including the Jan Morris work.

“The San Marco is a real cafe—the outskirts of History stamped with the conservative loyalty and the liberal pluralism of its patrons,” wrote Magris, adding that any place where just one tribe sets up shop is instead a pseudo-cafe. Didn’t matter if such a place was frequented by “respectable people, youth most-likely-to, alternative lifestyles or à la page intellectuals.” All endogamies were suffocating, he wrote, as were colleges, university campuses, exclusive clubs, master classes, political meetings and cultural symposia. “They are all a negation of life, which is a sea port,” he wrote.

Magris was right. Sea ports were different types of cities, where the gloriously convoluted residue of history washed up on the shores of every person’s identity. Especially in Trieste, such was life. One singular, classifiable demographic could never possess Trieste. And Caffè San Marco really was a microcosm of the city itself.

In Microcosms, Magris went on to describe the variety of folks at San Marco. He mentioned old long-haul captains, students revising for exams and chess players oblivious to what went on around them. There were “spirited old men inveighing against the iniquity of the times,” “know-it-all commentators,” “misunderstood geniuses,” and of course “the old imbecile yuppie.” In other passages, Magris compared Caffè San Marco to Noah’s Ark, a Platonic academy, and a hospice for the brokenhearted. Microcosms was required reading for any intellectual traveler to the Northern Adriatic.

When Delithanassis acquired San Marco, he already owned a small bookshop and publishing house across the street, so he just moved the bookshop into San Marco instead, where he was now re-establishing the cafe as a literary and intellectual nerve center of Trieste. Located to the left as one walked in, the bookstore was a perfect enhancement to the San Marco mystique. A poster showed me that author events were unfolding on a regular basis.

Such was the future of Caffè San Marco. A literary coffee shop reborn for the modern era.

Later as we reconvened outside on Via Donizetti, which was permanently closed off so that San Marco could fill it up with outdoor seating, Meloni and Delithanassis continued to smoke Marlboros and Chesterfields. They were both collaborating on a new calendar project, one that would include every possible religious holiday for every possible denomination or faith. They joked it would enable people in Trieste to get more days off.

“People tell us Trieste is the Napoli of the north,” said Delithanassis. “Nobody wants to work.”

We laughed out loud. For once, I wanted a smoke. But all I could do was listen to their stories and relish in the Triesticity of it all.

Marvin

September 30, 2022 at 5:14 am

Nice article by Gary Singh. Trieste is now on my bucket list. I don’t drink coffee… so is there also a ‘tea culture.’? Also, might have missed this… is the food more Austrian than Italian?

Gary Singh

October 3, 2022 at 9:56 am

The food, I would say, is all of the above. Sea ports are different types of places. Everything just washes up onto the landscape …