Canada Day

Canada Day, observed on July 1st, is a national holiday marking the anniversary of Confederation in 1867, when the British North America Act came into effect. It was originally known as Dominion Day until it was renamed in 1982.

Celebrated overseas, Dominion Day was a way for Canadians to celebrate their national identity and assert their distinctiveness within the British Empire. During the First World War, Canadian soldiers stationed in the United Kingdom took part in events such as log-rolling exhibitions and baseball games, asserting a rugged Canadian masculinity.

In the mid-1920s, members of British Columbia’s Chinese communities organized Chinese Humiliation Day as a counterpoint to Dominion Day to protest the 1923 Chinese Immigration Act that blocked most Chinese immigration to Canada. Members of the community wore badges reading “Remember the Humiliation,” organized speeches and distributed leaflets.

The Diamond Jubilee

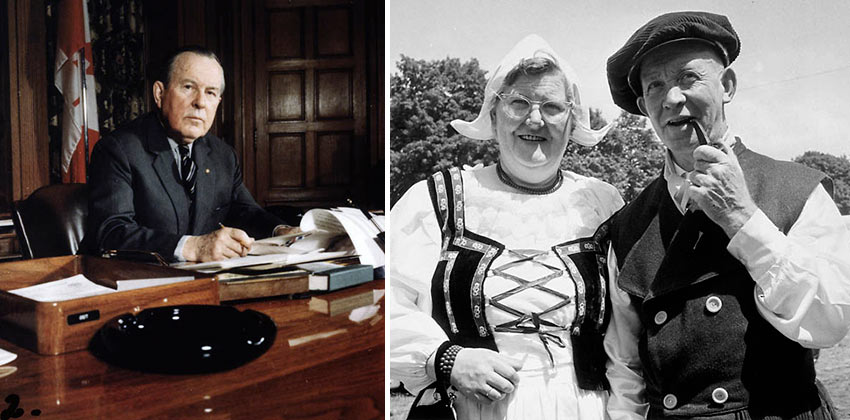

Federal government plans to hold a major event to mark the 50th anniversary of Confederation in 1917 were overshadowed by the First World War. As a result, the Diamond Jubilee celebrations of 1 July 1927, marking the 60th anniversary of Confederation were the first major federally sponsored Dominion Day activities. The centrepiece event for the day was a simulcast radio broadcast — the first of its kind in Canada — featuring an address by Prime Minister Mackenzie King and a dramatic pageant. Communities across Canada marked the Diamond Jubilee in various ways that emphasized local conceptions of Canada. This included parades of thematic and historical floats in Ottawa and Toronto, and an elaborate pageant in Winnipeg that highlighted its Eastern European immigrant communities. Indian agents in some regions allowed members of First Nations communities to be part of local Dominion Day pageants wearing traditional costumes, while others sought to emphasize messages of assimilation and conversion.

Federally Sponsored Celebrations in Ottawa and across Canada

In 1958, at the urging of Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, Secretary of State Ellen Fairclough organized a federally sponsored Dominion Day celebration on Parliament Hill. The event included a speech from the Governor General, a 21-gun salute, a military trooping of the colour and a carillon concert. By celebrating Dominion Day on an annual basis, Diefenbaker hoped to revitalize awareness of Canada’s British heritage, and reverse a recent trend of phasing out the use of the word “Dominion” from federal institutions. In subsequent years, his government continued to stress elements such as the monarchy and the military, but in the early 1960s, the Parliament Hill events began also featuring folk dances and folk songs in an effort to appeal to new Canadians and children.

The Liberal government of Lester Pearson decided to use Dominion Day events in Ottawa as a way to ramp up enthusiasm for the 1967 Centennial, and increased the budgets for these events to cover the costs of bringing in performers from across the country to take part in a televised variety show on Parliament Hill. These performers were selected with an eye to emphasizing a new conception of Canadian identity that was more explicitly multicultural and bilingual. Every year featured performances from different ethnocultural communities, as well as a significant francophone element, which always included both Québec-based performers and ones from other parts of the country. These events included First Nations performances, but normally in ways that fit a narrative of the assimilation of Indigenous peoples. Perhaps the most explicit example of this was the 1965 appearance by the Cariboo Indian Girls Pipe Band, a bagpipes performance by a group of Scottish tartan–clad teenaged girls from a residential school in Williams Lake, British Colombia. Among the many Centennial events of 1967, July 1st on Parliament Hill featured a massive birthday cake, which was cut by Queen Elizabeth II at an event hosted by Secretary of State Judy LaMarsh.

During the decade following the Centennial, less emphasis was placed on Ottawa-based celebrations of Dominion Day, as attention shifted in part to provinces celebrating their centennials. The variety show approach persisted, hosted at the National Arts Centre or on Parliament Hill. Although these events continued to draw local crowds, they attracted less attention from the CBC/Radio-Canada and audiences across the country, and were cancelled in 1976.

The election of the Parti Québécois in November 1976 spurred a massive revival of federal interest in the potential of using July 1st events to foster national unity. Although not explicitly using the term “Dominion Day” — they preferred formulations like “Canada’s Birthday” — in the late 1970s Ottawa pumped millions of dollars into both major national celebrations, televised on the CBC to communities across the country, and local celebrations which received seed funding for their activities. Although these broadcasts hoped to support feelings of national unity and were widely viewed across the country, they were more warmly received in English-speaking Canada. In Québec, the Fête nationale events of 24 June attracted larger crowds and higher-profile performers.

In the aftermath of the 1980 Québec referendum, the federal government shifted its focus and financial supports to emphasize observance of July 1st at the local level. Although still organizing concerts and formal events for Parliament Hill, the main focus was to stimulate community-based celebrations. A national committee for Canada Day (as the holiday was called after 1982) provided seed funding to communities to organize Canada Day events. It also suggested activities to link communities together, such as noonday singings of “O Canada” (adopted as the national anthem in 1980), and annual themes such as explorers, transportation or young achievers that were featured in activity books produced for children.

Throughout the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, a clear emphasis on bilingualism and multiculturalism was maintained in federal messaging about Canadian identity on July 1st, including in the selection of performers at events and individuals who were featured in official Canada Day publications. Representations of Indigenous peoples shifted substantially over these decades, moving from an emphasis on assimilation to greater celebration of First Nations, Métis and Inuit cultures, including performances in Indigenous languages on Parliament Hill by the 1990s.

Contemporary Celebrations

Since the late 1980s, Canada Day festivities in Ottawa have settled into a standard pattern. Formal ceremonies take place at midday on Parliament Hill, and include speeches by dignitaries, often including the prime minister, heritage minister and governor general. These events normally feature an inspection of the military guard by the governor general, and some more popularly oriented elements including music and dance performances. A flyover by the Snowbirds is common. The evening activities are more explicitly popular in orientation, and usually feature a massive concert with performers from across Canada, capped off with a major fireworks display. The midday and evening events are usually televised on the CBC and Radio-Canada.