The Skeleton Coast is one of the most appropriately named stretches of land in the world, a place where many hapless sailors of centuries past have mingled their bones with whale ribs and shipwrecks.

There was at one time no margin for error for sailors rounding the Horn of Africa and heading north through rough seas past this vast expanse, which stretches along the northern third of Namibia’s coast. The region borders more vast expanses, among them the world’s oldest desert, the Namib. One wonders whether whalers and sailors who somehow made it ashore after reefs had thrashed their ships found a moment to appreciate landscapes that would have challenged even the surreal imagination of Salvador Dali.

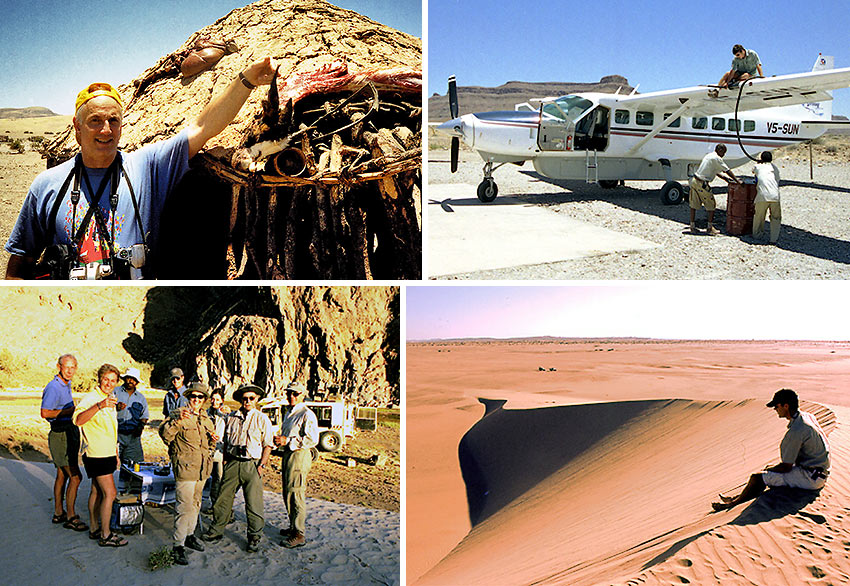

Along the coastline are immense flat plains, broken in places by lines of small cones denoting abandoned diamond mines. The plains yield to giant, orange-yellow sand dunes. The wind etches geometric patterns on their long curves and slopes.

Walking across a flat plain from our vehicle – a Land Rover with old airplane chairs strapped to the roof – my companions and I step in each other’s footprints to minimize the impact on the tiny blades of vegetation that suck moisture from the ocean fog.

After hiking up a dune’s long backside, we slide down its steep interior slope. Suddenly, the sound of the wind is drowned out by the eerie monotone crescendo of a double bass. But there are no double bass players in sight.

The musicians, in fact, are us. The dunes’ uniquely shaped sand grains emit a deep roar as they grind together. Delighted, some of us take long leaps down the slope, adding staccato notes.

Struggling back up the huge half-bowl slope, the solitude of the coast hits home. Despite a huge concession set aside for the Skeleton Coast Camp – which is where we are staying – it is limited to 12 visitors at a time.

I keep imagining the challenges shipwrecked sailors would have faced. If I were in their shoes, would I have been able to overcome fear and march up the coast, giving my skeleton a run for its money?

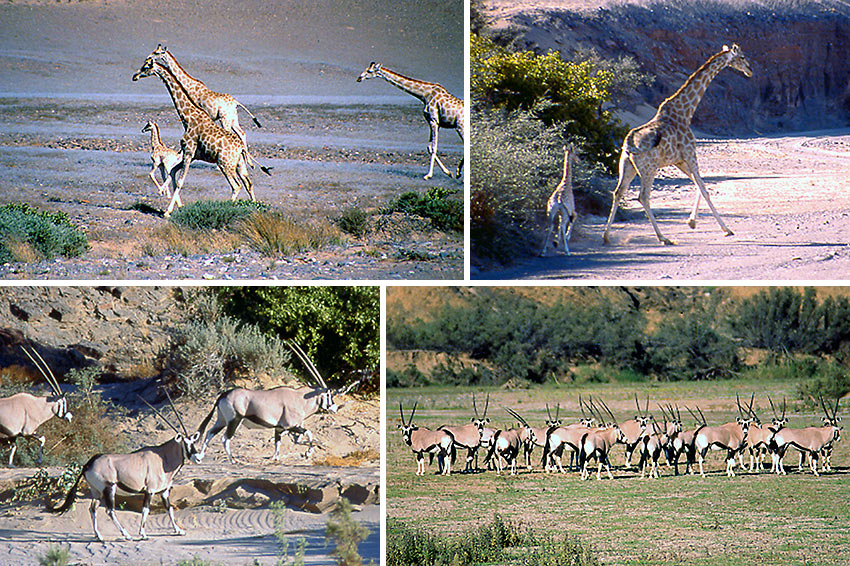

Yet there are those that survive in this environment. The wildlife is fascinating in how it has adapted to the desert conditions. Up on a ridge facing the ocean breeze are several gemsbok, or oryx, weighing nearly 230 kilograms each. A type of antelope, they hyperventilate in the ocean air in order to cool their body temperatures. Their horns are like scimitars, forcing the region’s desert-adapted lions to think twice. Fresh lion tracks in a river bed make me think twice when, separated from the only other vehicle, I collect flat rocks to jam under tires bogged down in dry sand. A bit inland, amid arid canyons and valleys, are ostriches, jackals, mountain zebras, baboons and foxes.

Even the bugs are amazing. I saw a beetle that satiates its thirst by using grooves in its back to build up a drop of water from condensed fog.

Desert elephants sometimes venture to the coast and surf the dunes, creating their own symphonies. We track the elephants on foot – they’re always just around the bend, judging by the fresh elephant dung – but the sun reflecting off the walls of a clay canyon beat us back. Our vehicles cause us to throw in the towel as well, as an unexplored river bed that might leave a vehicle stuck becomes too forbidding near sunset. There are no tow trucks here.

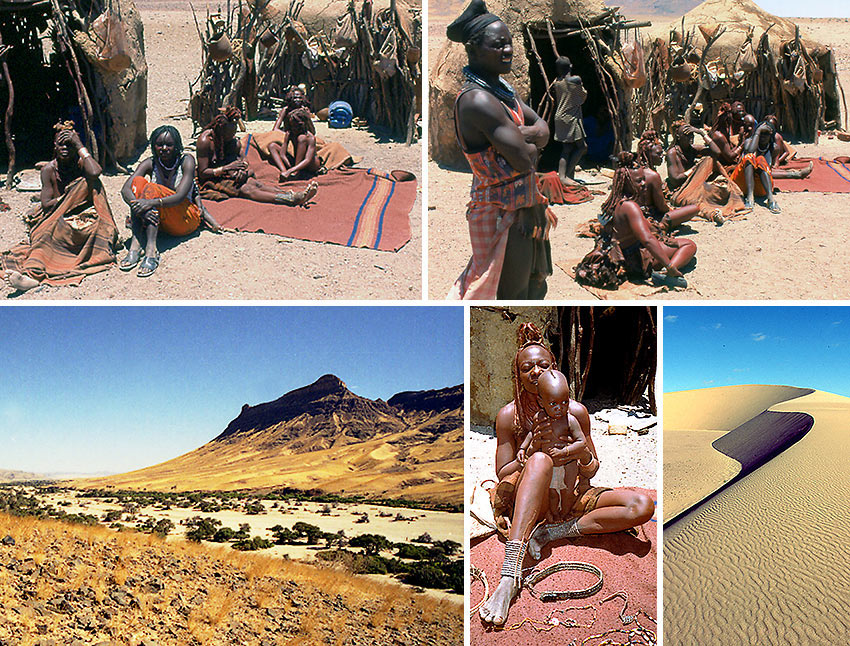

But the greatest survivors are the members of the Himba tribe, some of whom reside just outside the park. Scattered across northern Namibia, they make up less than 1 per cent of the population. They haven’t changed their nomadic lifestyle in centuries, raising cattle and living in huts of dung and sand.

The women are particularly striking, wearing only goat skin aprons and jewellery that glows red from a mixture of ochre and rancid butter, rubbed daily over every square inch.

With their braided hair coated with mud and hardened like a helmet, these women work hard while the men count their cattle. The women’s true beauty is rooted in their physical strength and a meticulously tended traditional appearance that, according to anthropologists, maintains their cultural identity and protects them against the vagaries of modern life. Their refined beauty is framed by the harsher beauty around them.

Horrors such as the diamond wars farther north in Angola, the heartbreak of AIDS orphans, tribal conflicts and deprivation magnified by an envy of wealth have missed the Himba in this neck of Namibia. The elements of their neighbourhood are so tough no one hungers for their land – it’s safety in lack of numbers.

A couple of decades ago, a drought – the term is relative here – killed enough cattle to drive some Himba into the towns. They didn’t fare well – alcoholism and prostitution were often the byproducts of poverty and culture shock. Much farther east, a proposed dam threatens the Himba way of life. But on the Skeleton Coast, it’s likely that in 50 years, the headman’s progeny will still be tending the holy fire, a smoldering log that is said to help departed paternal ancestors bring good fortune to the tribe.

At night, I stand watching the sky, stealing glances at the silhouette of a jackal slipping around my tent, which by Himba standards is as luxurious as the Taj Mahal. Before the morning fog, the night is moonless but bright. The stars are the brightest and most numerous I’ve seen, and shooting stars abound.

None of the hemisphere’s constellations are familiar. It’s an alien world, beautiful as long as I know a prop-driven aircraft will eventually alight on our desert runway with ample provisions.

GETTING THERE: Tour operators such as Wilderness Safaris, which operates the Skeleton Coast Camp, offer flights into the park in small bush planes from various points in Zimbabwe, Botswana, Malawi, Namibia and South Africa, and Skeleton Coast Camp for a four-day, three-night safari package.

For more visitor information, visit the Namibia Ministry of Environment

Growing up in Kansas, Skip Kaltenheuser was tuned to travel by a traveling salesman father’s pedal to the metal vacations. He extended his reach with travel writing, and efforts such as supervising elections and doing special projects. When they’re willing to slum with him, Skip’s favorite travels are still with one or both kids, now young adults, neither indicted despite living in Washington, DC their entire lives.

Growing up in Kansas, Skip Kaltenheuser was tuned to travel by a traveling salesman father’s pedal to the metal vacations. He extended his reach with travel writing, and efforts such as supervising elections and doing special projects. When they’re willing to slum with him, Skip’s favorite travels are still with one or both kids, now young adults, neither indicted despite living in Washington, DC their entire lives.