Since the Covid virus invaded South America, I have been living in Mindo, a tiny pueblo completely surrounded by the forests of Ecuador’s Andes cordilleras. I begin each day watching the clouds crawl across the mountain tops while I type computer code.

Ecuador ranks 25th in the list of Covid-related deaths per capita per nation, according to the Johns Hopkins University. But my friends here in Mindo doubt this statistic. “The death rates are much higher,” they insist. “Look at all the coffins outside the hospitals. There are so many uncounted deaths.”

A few months ago, I nervously watched two coffins borne past the town plaza and into the local church. “Oh, no!” I thought. “The virus has finally invaded this remote pueblo!”

I asked a friend about them. “Not Covid,” he assured me. “They were driving drunk on a motorcycle.” He shrugged. “These days, what else is there to do? There are no jobs.”

My friend is a chef in Mindo. Locals know him as Signor Crab because he sautés crabs in coconut milk and spices, in the style of his coastal village. Before the pandemic, we barely had time to talk because he was too busy serving his signature dish to tourists visiting the pueblo. Nowadays, I see him sitting alone in Mindo’s formerly bustling, now silent, plaza. Without a job, Signor Crab asked me if he could cook for me in exchange for money. He told me he needed to buy medicine for his two sons.

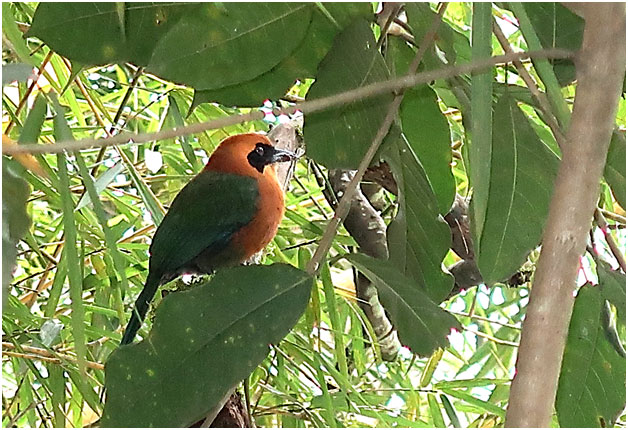

I am in Mindo to study the cloud forests around me. Each cloud forest is a unique habitat, a home to scores of plant and animal species that are found only in Mindo. Over eons, these forests formed when the Pacific Ocean’s warm vapors wafted against the cooling Andes peaks, creating the ideal environment for orchids, bromeliads, and ferns. These mountains are home to Guadua Augustoflora, the South American bamboo that, with greater efficiency than most plants, sucks carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and converts it into material used to build local houses.

Before leaving the United States, I worked on environmental, computational models. Now, I use Artificial Intelligence and satellite images to track tree cover loss in these forests. My studies suggest that in the past two years, in a place about a third the size of Washington, DC, Mindo lost tree cover in an area equivalent to more than 3000 tennis courts (Tracking Cloud Forests With Cloud Technology and Random Forests).

These trees are victims of the perfect storm brewed by joblessness, poverty, record gold prices, Covid, and climate change. The desperate poor hunt for gold in illegal, artisanal mines. The rich raze forests to build country homes to escape Quito, Ecuador’s congested capital, where infection rates are at an all-time high. Beyond these immediate threats, climate change insidiously destroys Mindo’s ecosystem. With warmer temperatures, the clouds to which the trees have adapted over thousands of years are dissipating.

The same week I witnessed the funeral of the two victims of the motorcycle accident, the International Panel for Climate Change issued its report, referred to by the United Nations’ Secretary General as a “code red for humanity.” Destroying the Andes cloud forests amounts to a negative, feed-back loop: the forests around me can potentially buffer the world against the effects of greenhouse gases; but they are being destroyed partially because climate change is wreaking havoc on local farms that must contend with dramatic, climactic changes.

At the end of each day, I watch the clouds drift down from the heavens to rest upon Mindo. They are like feathery intimations of hope. As long as the clouds persist, so too will the forest ecosystem.

Similarly, I see hope in the stoic persistence of Signor Crab and of my other friends on Mindo’s streets: the shopkeepers; the Venezuelan refugees; the artisans and buskers. They stake their lives on ecotourism. They know that without the trees, the tourists will not return if and when the world regains some version of normalcy after the pandemic.

Stubbornly, I make the deliberate choice to cling to hope. On Tuesdays, I muster hope by teaching data science and Artificial Intelligence to a small group of students. They are graduates of Mindo’s school for at-risk families. All of them are healing-from poverty’s ills; from familial instability; from domestic abuse; from the violence of classism, racism, colonialism, and sexism.

My ambitious students are my heroes. With each backpacking, laptop-toting tourist they see in Mindo, my students are reminded that opportunities exist beyond their threatened mountains. They talk about this as they type their code and run their algorithms, using my project to monitor deforestation as an example of Artificial Intelligence’s power. They muse that perhaps in the future, they might conquer the virtual, data-intensive world of rich nations, in the way their ancestors’ lands were once conquered by white Europeans.

My students dream of the future. They want to conduct non-extractive, profitable, sustainable work. They want to produce knowledge-based goods and services for the world. My students-who have lived their entire lives among the marginalized and the discarded-long to conduct creative, intellectually challenging work…while being nestled within Creation’s embrace…while being nurtured by the Divine work unfolding among the clouds.

For more on Mindo, Ecuador, read Mr. Pasky Pascual’s scientific journal of Life in Mindo, Ecuador.

Noel

June 15, 2022 at 10:15 am

Great article about Mindo your new place, Pasky. Regrettably, I didn’t quite make it there. But will keep it in the itinerary and will make sure to look for senor Crab.

You will certainly be missed amigo. RIP