Directed by: Jean-Pierre Melville

Directed by: Jean-Pierre Melville

Screenplay: Jean-Pierre Melville, Georges Pellegrin (Joan McLeod: novel, uncredited)

Cinematography: Henri Decaë

Editing: Monique Bonnot, Yolande Maurette

Music: François de Roubaix

Cast: Alain Delon, François Périer, Nathalie Delon, Catherine Jourdan

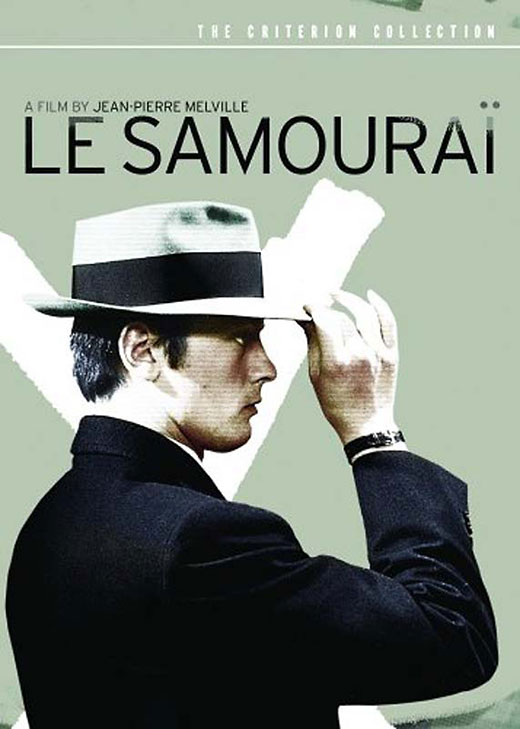

Melville’s Le samouraï

By Walt Mundkowsky

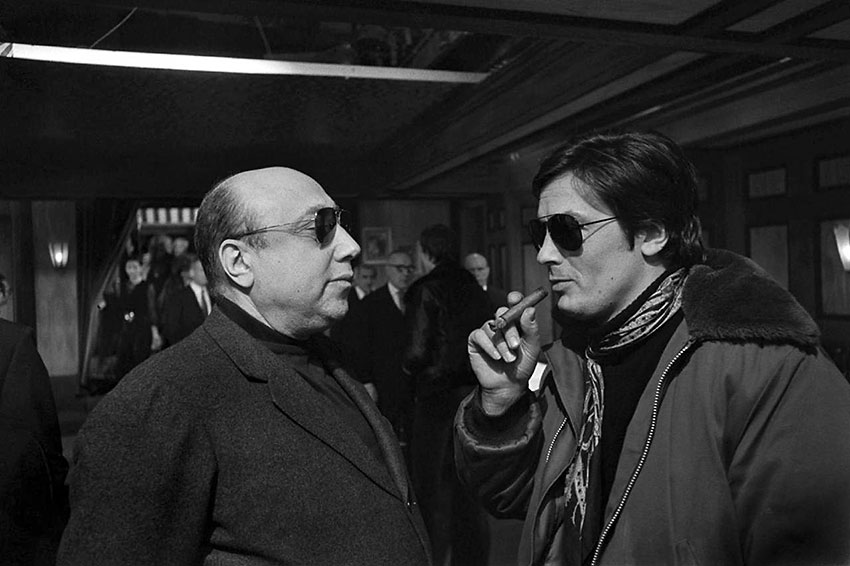

French filmmaker Jean-Pierre Melville (1917-73) is hard to pigeonhole. He operated outside established channels (eventually running his own studio) yet he employed movie stars. An inspiration to the New Wavers who liberated French cinema, he remained a consciously classical technician. Abroad he’s best remembered for a trilogy of gangster dramas — Le doulos (1962), Le deuxième souffle (1966) and Le samouraï (1967). The last of these is the easiest of the trio to admire — character, structure, and surface are seamlessly joined.

Jef Costello is a contract killer. He daringly completes his current assignment (a nightclub owner) during business hours, relying on an airtight alibi to prevent capture. His girlfriend Jeanne swears that he was with her until Mr. Wiener, the elegant gent who keeps her, arrived. He sees Jef leaving the building, and fingers him for the police. Wiener hopes to sink Jef (he knows his mistress has been deceiving him), but he unwittingly supports the alibi. Even so, the police inspector thinks Jef guilty and has him watched. Things start to crumble for Jef when the bigwig who ordered the hit gets nervous about the cops and tries to pay him off with a bullet. Jef moves ahead on two fronts: to evade arrest while tracking down his employer.

Professionalism is a byword in Melville’s moral universe. Jef not only kills to live, but lives to kill. He stays in a dingy hotel, with a pet bullfinch for company. (The bird is probably closer to him — and more loyal — than any human.) From the moment early on when he refuses to acknowledge a beautiful woman’s smile from a passing car, Jef is sealed within a circle of obsessions. His connection to Jeanne fascinates in its ambiguity; not precisely romantic, it bristles with crossed wires — she wants to be made useful, as he strives to shield her from danger.

Melville’s extraordinary goal is evident in the opening frames: to make a black-and-white film in color. Except for the subway scenes (shot documentary-style), the interiors conform; grays and browns dominate. Outside views are trickier, but the overcast skies (easy to locate in Paris) and nighttime settings help. (François de Roubaix’s music also uses subtle colors, led by a dry trumpet and harp.) The cutting is so assured that the long stretches without dialogue seem pointed and shapely, as the director links his cops and crooks by activity and behavior.

Each panel of Melville’s triptych highlights a particular actor, and Le samouraï is the ideal arena for Alain Delon’s chilly perfection and inward-looking gaze. The less-is-more aesthetic extends to the female co-stars. Nathalie Delon (Alain’s wife at the time) projects nobility and strength as the steadfast Jeanne, and Cathy Rosier’s sleek nightclub pianist is both ally (refusing to identify Jef) and rival. The inspector contains as much of Melville as does Jef, and François Périer is brainy, commanding and crafty. It’s tough to evade the shadow of René Descartes (1596-1650) in describing him.

Back when, I bet a friend that I could review this without mentioning its camerawork by Henri Decaë — important to Melville as early as 1949 (Le silence de la mer) and 1950 (Les enfants terribles), and a key figure for the French New Wave and others. Zero interest in winning that one.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.