Story and Photographs by Gary Singh

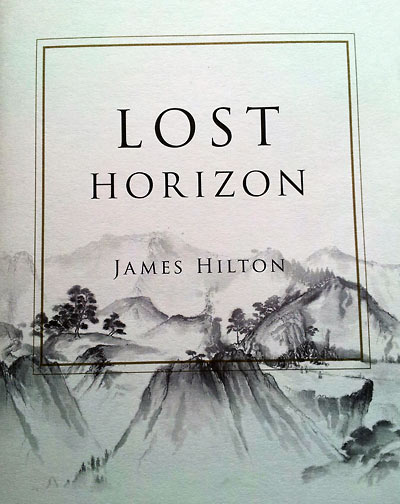

“…to tell his whole story in the past tense would bore him a great deal

as well as sadden him a little.” – Lost Horizon

“We only sell tea to go,” says the woman at Ten Fu Tea in the Aberdeen Centre shopping mall in Richmond, British Columbia.

Motionless and disappointed, I contemplate leaving but something tells me to stay. Outside in the mall, the low-frequency roar of a water fountain complements the higher-pitched Chinese instruments—erhu and pipa—that I hear emanating from the canned system. Inside Ten Fu, as I start to nose around, I see a wide variety of loose leaf pu’erh, oolong, and black tea. Tiny $150 cast-iron pots occupy the shelves like royalty. Statues, gifts and figurines abound. I order pu’erh in a paper cup, hoping its earthy muse-like tendencies will harmonize the eastern and western spheres of myself.

Asian and Asian Canadians make up about 60 to 70 percent of Richmond’s population, much of which is Hong Kong Chinese. Parts of Richmond remind me of Hong Kong, but without the density and without the skyscrapers. Hundreds of Asian restaurants, eateries, tea shops and hole-in-the-wall joints populate the landscape. Eccentric old side-streets bisect lengthy Los Angeles-style thoroughfares.

Everywhere I roam, Asian-themed shopping centers seem to emerge over and over again. Some are new and shiny, while others evoke more grungy atmospherics. Aberdeen Centre is one of the newer ones. On a previous Richmond visit, in 2004, I got to see the mall when construction was still underway. Now it’s a shiny, angular and well-illuminated place thanks to multicolored glass paneling on the top floor.

All in all, Richmond is a righteous town in which to explore one’s lost eastern half through the muse of tea. I don’t mean “lost” in a negative sense. To paraphrase Ikkyu, the heroic drunken Zen monk of yore: If I don’t have a destination, then I can’t possibly get lost.

The senior-aged woman inside Ten Fu looks horrified by yours truly when I walk in. Maybe she’s not accustomed to a Zappa-looking freak with a Moleskine notebook ordering a dark pu’erh, claiming it connects him to the earth in some strange quasi-yogic psychobabble.

There’s no place for me to camp out with a pot, but somehow she can tell I’m a serious tea drinker, so she fills a plastic steeper with pu’erh leaves and lets me hang out and stare at all the multicolored tins of tea and Buddhist figurines. After a few minutes of my lazy browsing, she motions for me to park myself at a ceremonial mahogany table near the back, where I take a cup of the tea. A laughing Buddha statue sits in front of me, with large auburn mala beads hanging around his neck.

She slides me a bowl of pumpkin seed candy, fantastic mega-sugary stuff, and then moves away to help other customers, all Chinese. I assume I’ve won her over. She no longer looks horrified.

I can only guess what’s happening. Since a majority of westerners roll in and order something like the stock Jasmine tea in a box—the generic uncreative stuff—maybe she assumes I’m a different kind of customer, that is, one who at least knows pu’erh, one who has a preference. As my wannabe Zappa-turned-Kerouac self sits there scribbling in my notebook and scarfing the pumpkin seed candy, there’s nothing for her, or me, to be confused about. By now, the pu’erh has elicited serenity of the utmost sort.

Dharma and the Mysterious Third Ingredient

Directly across Cambie Street from Aberdeen Centre, the Vancouver International Buddhist Progress Society occupies the sixth floor of the Radisson Hotel building—the only such scenario on earth. There’s a temple, a bookstore, classrooms, a jewelry and souvenir store, plus a tea shop. Upon my arrival, I’m the only one in the tea shop. Everything seems the same beige color: the tables, chairs, walls, everything. Soft piano jazz emanates from the speakers above me.

An older Chinese lady toils away behind the counter and looks utterly horrified when I walk up. I guess I still don’t look like a tea drinker. She hands me a laminated menu and I scan the offerings. Pointing to ginger longan tea, I say, “This one.” She speaks no English, but she acquiesces and motions for me to sit anywhere in the shop, which is still empty.

I slither into a table at the front corner as she gets on the phone to call someone. I understand no Chinese, but I can tell she’s phoning for help. Within a minute, a young woman comes over from the temple area down the hall and informs me that the tea shop doesn’t take cash. I have to get a meal ticket. And my pot of tea is seven dollars. No problem, I say, getting up.

After walking over to the temple area, I see a few ladies behind a check-in table, wearing what look like red flight attendant uniforms. I give them the cash and they issue me a small laminated ticket. The temple is closed off at the moment, so nothing’s going on. I migrate back into the tea shop and give the woman my ticket. She apologizes in Chinese for the trouble, managing the word, ‘sorry’ in the middle somewhere.

The tea arrives ten minutes later. A see-through glass pot reveals strange unidentifiable meaty-looking mélange in the infuser. Turns out it’s ginger, longan and something else I can’t identify. In fact, it’s hard to tell the ginger from the longan.

The tea is amazing. A sweet fruit-like symphony of taste seems to sand down the edges of the ginger notes. Gorgeous. Sad to say, I feel ashamed to admit I don’t know what a longan is. I should.

I ask the woman about the ingredients and she can’t answer. But she manages to say, ‘ginger,’ ‘longan’ and one other ingredient, in Chinese. For that third ingredient, she apparently only knows the Chinese word. After looking at the pulpy experiment enshrouded inside the tea infuser, I am obsessed to learn about this third ingredient. Some kind of fruit, but I can’t tell.

The woman can sense my intrigue, so she dashes out of the shop and returns a moment later with the janitor, a short elderly Chinese man wearing shop overalls. He had been pushing a wheeled garbage can down the hall.

“Do you need help?” He asks.

“I just want to know what’s in this,” I reply, pointing to the infuser. All three of us then laugh. Ginger, longan and some other Chinese thing? I ask.

“I don’t know how to say that in English,” the janitor says.

I ask the janitor to write it down in Chinese, which he graciously does. I then blast it all over Facebook so my Chinese friends can translate. Turns out it’s a dried red date, or something similar.

The mysterious third ingredient. I probably could have figured it out, but I just like saying that phrase: “The mysterious third ingredient.” It has a ring to it. I can’t tell if I’m in a Graham Greene story or a cold war-era John Le Carre novel. But I am serene in the mystery.

When I get up to leave 45 minutes later, I am still the only one in the shop. The woman says thank you in English. I attempt to say xie xie but fail miserably.

Go West, My Wayward Son

If Richmond constitutes an intrinsic place to salvage the lost Eastern half of myself, then Victoria just across the water on Vancouver Island presents an opportunity to salvage the lost Western half. And when those two eventually meet and fuse together, the result is Shangri-la, as we will see.

For starters, I’m at the end of the tea bar at Silk Road Tea, just outside Victoria’s Chinatown, looking at a wall of oolong, black, white, green and herbal teas. Tourists enter the shop straight off the bus seemingly every five seconds. Gifts and tea supplies occupy shelves everywhere. As I spend an hour with a pot of earthly-dark brown pu’erh, I scope out numerous designer tea steepers, infusers, mugs, timers, strainers and displays of exotic glassware, ceramic and cast-iron tea sets. The tourists and nuclear families seem startled and horrified at some loudmouth like me sitting at the end of a tea bar, carrying on about tea as the muse of creativity, fusing the mental with the physical.

The barista dude is an expert. He waxes poetic on all things tea, not just for me, but to anyone who comes in. The pu’erh is connecting me to the earth, so his commentary is refreshing. Not very many people walk in and order pu’erh, he tells me. They usually want the floral stuff.

In my best sober Jack Kerouac English, I say to the barista dude: “You know, I just need to find some esoteric Chinese place with lizards crawling across the fibrous wooden floor, tons of ginseng root hanging on twine, fucked up herbs in every tin cylinder, and a cast iron pot of earthy pu’erh, blacker than the ace of spades, bark-tasting, the kind that shatters the space-time continuum and reconnects me to Tang Dynasty hermits. And then the solitude will be enhanced even more. Know any places like that around here?”

He can’t recommend any, but he appears sympathetic. In any event, Silk Road is unique among tea shops. Each tea has a title and a subtitle. Alchemist’s Brew is “Tea of Transformation.” Herbal Chai is “Cosmic Consciousness.” Sublime is the “Monk’s Elixir.” That last one calms me down, considerably so.

Love and Wisdom

Victoria’s Chinatown is not that big, just a few blocks, but it’s the oldest one in Canada. After leaving Silk Road, I go through the Gates of Harmonious Interest right to Venus Sophia where I find the Prince of Darkness. That is not hyperbole. That’s exactly what unfolds.

The Gates of Harmonious Interest are 40-feet high. The structure is a landmark built in Victoria’s sister city, Suzhou, and presented to Victoria in 1981, partly to memorialize the 61 Chinese-Canadians who fought and died in World War Two. The monument symbolizes a combination of opposites, yin and yang, or to be more precise—unity in duality. Male and female lions grace each side of the entrance. Singh means lion, so I feel at home. Just down this particular street, Fisgard, I discover the goddesses of love and wisdom.

Venus Sophia is a tea shop and vegetarian eatery filled with eclectic furniture, paintings, vintage bicycles on the walls, Indian travel books and tea supplies. A golden pu’erh beckons me and I slide into a corner table after ordering a pot.

Victoria is definitively British, but from the view of my western half, this place, Venus Sophia, this soothing little sanctuary in Chinatown, this gorgeously oddball tea shop, puts me on a course toward finally harmonizing the inner polarities. For a moment, I feel a sense of belonging. No more of this Nehru-style, “mixture of East and West, out of place everywhere, at home nowhere,” stuff.

Venus Sophia even sells Oso Negro coffee from not too far away. A blend called Prince of Darkness stares right at me from the shelf. Unfortunately, a complimentary blend, Princess of Darkness, is sold out. There’s none left. Somehow, I find this to be symbolic of my whole journey, in some strange Jungian, animus-and-anima sense.

Kipling’s Empress Muse

The Canadian capital of high tea, Victoria’s Fairmont Empress, was the first property to establish the concept of British-style high tea society anywhere in North America. I also learn, via some impossible cosmic transmission of tea sommelier knowledge, that Rudyard Kipling considered this hotel to be his muse. He drank tea here about the time it first opened, in 1908.

In fact, Kipling visited Vancouver Island a few times. Fortunately or unfortunately, he didn’t have to deal with convoys of tour buses all day long, or incessant amounts of whale watching rubberneckers from across the planet, but he raved about the island in various letters and other writings. He praised Victoria as a fine Devon-style country land where retired civil folk from the good old British Empire could sit around and productively loaf. Photos of Kipling, among various royal family members, highlight quite a few walls, in and about the property.

The tea room, a mammoth space, (for a tea room, that is), serves 500,000 cups of tea each year. I am grateful for the Devil’s Chocolate and Pistachio Battenberg, the Rose Petal Shortbread, and the Cognac Port Pâte on Sun-dreid Tomato Bread, all while I consume the Empress special blend of Assam, Kenyan black, Kenyan green, Sri Lankan Dimbula and Keemun. The special blend is a copper-colored symphony of notes and flavors, although my orchestration chops are long gone, so I can’t describe the different ranges of the instruments and how they complement each other in this fabulous blend of tea.

Since I am the only Zappa-looking dude in the whole place, which is filled with tourists and nuclear families, I sense a tad of uncomfortable stares, especially from the old blue-hairs. But I am dressed at least as good as most of them, oddly enough.

The Muse as Connection Machine in Shangri-la

Finally, the two halves meet and I feel integrated. Two lion-like statues on West Georgia Street in downtown Vancouver are my signals, my signposts, declaring that I have found Shangri-la. Everything comes into perspective, here, amid towering skyscrapers, glass, foliage, dismal skies, shopping, lattes, high finance, urban parks, plus outdoorsy-jacket-and-shorts-wearing cyclists in the pouring rain, and all the things that characterize Vancouver, one of my favorite cities on earth. And the Shangri-la Hotel is now the city’s tallest building.

Throughout the hotel, certain rooms and spaces are named after characters and scenarios from Lost Horizon, the book that gave us the word, Shangri-la. The hotel brand started in Singapore, the lion city, hence the two lions out in front. Again, my surname means lion so everything comes into perspective.

The Shangri-la brand already fuses east and west, even if it seems dumb and cliché to say it that way. Heck, these days, Vancouver feels just as much a part of Asia as it is a part of North America, really. Which is why I love it so much.

In Shangri-la, I feel more at home here than anywhere. No more disenfranchised Nehru stuff. I am serene, at least during the afternoon tea. As a result, I don’t even have to look for an excuse anymore. Everything about the Shangri-la, including the tea service, fuses native with exotic, intimacy with distance, east with west, yin with yang, serenity with chaos. That is the whole idea, from top to bottom, inside and out, around and between. I think the ancient alchemists were right when it comes to merging opposites and transcending duality. One becomes a more integrated person, as a result.

In the Shangri-la, Xi Shi is the bar where the tea service is presented. I am grateful to experience the Szechuan Peppercorn Creme Brulee, the Mango Cream with Sago and Pomelo, plus a Black Sesame Macaron atop a tiered platter next to my Single Estate Oolong from the Fujian province of China.

As I take in the last drop, realizing that each and every sip of tea is indeed a journey, like the aphorism goes, I notice the in-house guitar player is playing and singing a serene jazzy version of Van Morrison’s “Into the Mystic.” Way down past the lobby, I can just barely see the traffic outside on Georgia Street, but I hear none of it. I feel very, very Zen inside this place. There is no need to explore this land any further. I am done.

I end up leaving the hotel, and British Columbia, with my own hardback copy of Lost Horizon, a special version published by Shangri-la hotels, for which I am yet again very grateful. A piece of velum lies inside the front cover, regaling me with a quick history of the entire Shangri-la brand. I’ve read parts of the book before, but this copy is unique.

With the Single Estate Oolong still warming my system, I skip to my favorite passage in the book, where the belligerent Christian missionary woman is completely baffled by the monk’s life:

“What do the lamas do?” she continued.

“They devote themselves, madam, to contemplation and to the pursuit of wisdom.”

“But that isn’t doing anything.”

“Then, madam, they do nothing.”

“I thought as much.” She found the occasion to sum up. “Well, Mr. Chang, it’s a pleasure being shown all these things, I’m sure, but you won’t convince me that a place like this does any real good. I prefer something more practical.”

“Perhaps you would like to take tea?”