By Ed Boitano

The first thing you notice is the fragrance; where the intoxicating scent of the tiare flower announces to your senses that you are in a magical place, overflowing with tropical vegetation and soothing trade winds. It is the same perfume that the English seamen on the HMS Bounty first encountered; but they came not for flowers, but for breadfruit, intended as a new food staple for their African slaves in the West Indies. But that was another time and another emotional place. Today, Papeete, located on Tahiti Nui (‘Big’), is Tahiti’s vibrant capital city and gateway to her islands. Roughly one-half of all of the Tahitian islands’ population live in this city. Papeete bustles with world-class resorts, restaurants, nightclubs and endless shopping.

FIRST STOP: The Museum of Tahiti and Her Islands

The Museum of Tahiti and Her Islands (‘Te Fare Manah’) is located 10 miles south of Papeete and offers a concise overview of Tahiti and the other 118 islands of French Polynesia. The museum is divided into four sections: geography and natural history; pre-European culture; the effects of colonization; and the natural wonders of the archipelago. In less than two-hours you will become an expert in all things French Polynesia. Displays are in English and French.

Like many of the Pacific Islands, it’s a widely accepted theory that around three to four thousand years ago, there was a great migration from southeast Asia which led to the settlement of many Polynesian islands.

Feats of Courage

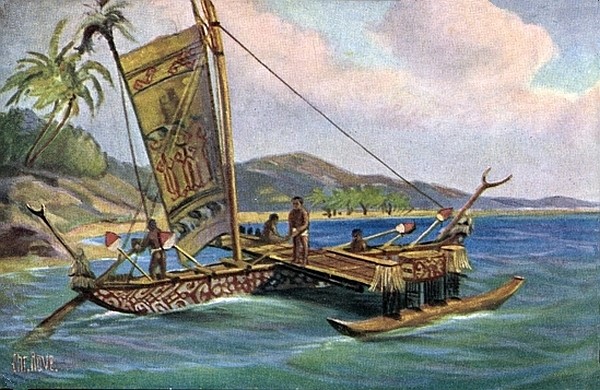

The ingenious Polynesian explorers were ultra-sophisticated sailors, with a highly complex navigational system based on the observation of the stars, ocean swells and flight patterns of birds. Their primary vessel was a 50 to 60 feet long canoe, consisting of two hulls, connected by lashed crossbeams. A precursor to the modern catamaran, the sails were made of matting drove and long steering paddles enabled the mariners to keep it sailing on course. The canoes could accommodate roughly two dozen people, food supplies, livestock of pigs and poi dogs, and planting materials, essential for the long expeditions and the eventual founding of new island colonies. Like athletes, they would go into vigorous training prior to voyages, even conditioning their bodies to deal with less food and water. The navigational voyages — voyages of spectacular feats of courage, strength and skill — are still widely admired today. Numerous canoeist groups have attempt to emulate the Polynesian voyages; but with the backup of small motors, charts and compasses and food items, they certainly do not qualify as a voyage into the unknown.

The European Conquest

During the 1500s, several European explorers sighted various Tahitian islands, but it was not upon Englishman Samuel Wallis’ arrival in 1767 that Tahiti, Moorea, and MaiaoIti were christened the Society Islands, named for the Royal Society, which had sponsored the expedition under Capt. James Cook.

This was followed by landings of French naval expeditions in 1800s along with further English ships. Packed with rugged whalers and strict Protestant English missionaries, an attempt was made to strip Tahiti of much of its culture, including even the traditional use of the canoe. Tahitians soon faced harsh biblical justice of prison, banishment and even death by the new European colonizers.

The British and French conquests provoked a gold rush fever between both nations for control of the islands, which concluded when King Pōmare V of the Pōmare Dynasty, who had ruled Tahiti until 1880, was persuaded to abdicate his throne in return for a French pension and two honorary titles, making him the last Tahitian monarch. The body of his mother, Aimata Pōmare IV Vahine-o-Punuateraʻitua (otherwise known as Aimata; ‘eye-eater,’ a custom of the ruler to eat the eye of the defeated foe) were removed and buried in the nearby Royal Mausoleum.

The earlier French-Tahitian War (1844-1847) set the stage for Tahiti and most of her dependencies ceded to France; by 1958, all the Islands of Tahiti were reconstituted as a French Overseas Territory and renamed French Polynesia.

A large harbor was built in Papeete, an international airport was constructed in Faa’a, and a huge film crew descended onto the islands to film the 1962 movie, Mutiny on the Bounty. These rapid changes quickly brought French Polynesia into the modern age. In 1977, the French government granted autonomy to French Polynesia; then in 2004, it became an official Overseas Country of the French Republic, with all its people receiving the full rights of French citizenship.

Louis-Antoine de Bougainville & the Noble Savage

But it was Louis-Antoine de Bougainville, the first French naval explorer to have circled the world (1766-69), who earlier created a worldwide sensation when publishing his travel log under the title, A Voyage Around the World. The book describes Tahiti as an earthly paradise where the noble savage lives in blissful innocence with one another, influencing the utopian thoughts of poets, novelists and philosophers. The Bougainvillea Flower stems from his family name.

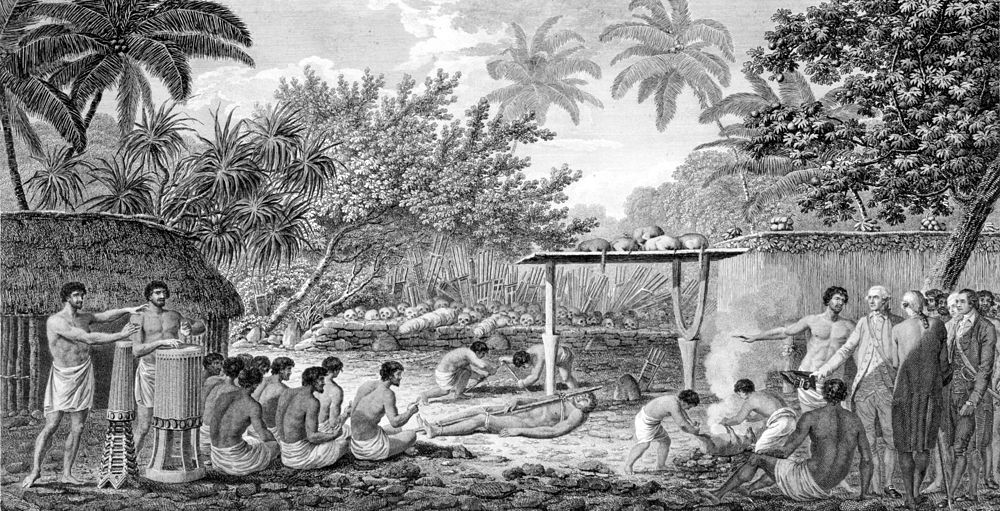

But were the islanders really an example of innocence and bliss? Human sacrifices were common, and the trade of iron nails with European conquerors — which Tahitians conformed into fishing hooks that would not break as opposed to the previous use of delicate seashells — were returned for water, food and sexual favors. Imagine the crusty English sailor, complete with rickets, scurvy wounds, broken smiles and missing teeth at the average height of 5 ft. 5 inches tall encountering statuesque 6th ft. tall Tahitian people born into a perfect gene pool. With the reduction of nails, some captains actually expressed concern that their vessels would collapses. And along with stealing (often eating) strange animals and general theft of supplies, the Tahitians demonstrated certain aspects of their culture that was not unfamiliar to humankind.

Paul Gauguin in Tahiti

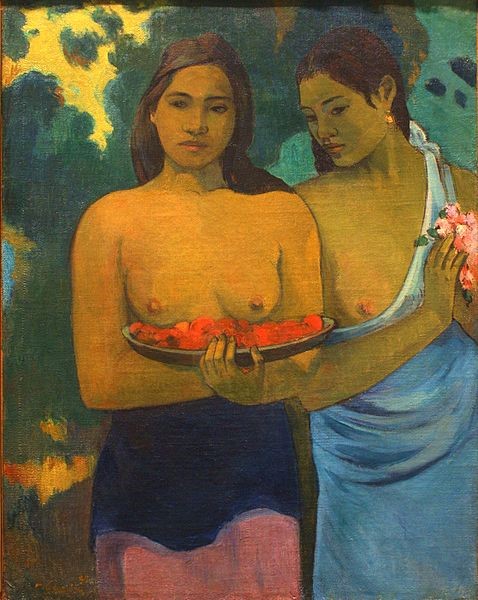

In 1891, Post-Impressionist French painter Paul Gauguin also relocated to Papeete. Middle aged at 43-years-old, he was disappointed to find that Tahiti’s mythical paradise and primitive life had already changed due to English and French colonization. To distance himself from ‘civilization’ he moved to the far west side of the island, ultimately completing 516 paintings, which included his oil on canvas: Two Tahitian Women, recently purchased at $300m (£197m), making it the most expensive work of art ever sold.

A Personalized Exploration

Arahurahu Marae, Tahiti Nui’s only completely reconstructed marae, is an open-air place of worship and ceremony. The sacred temple is constructed of tiers of lave stones where the Tahitian elite made sacrifices. Yes, sometimes even human. Only royalty is permitted to be inside a marae, even a rebuilt one, while commoners risk death by entering. My guide informed me that he had never once stepped into a marae. I couldn’t resist, and carefully climbed over the lava bricks. Somehow, I managed to survive.

Our jeep commenced deep into the mountainous valley of Papenoo; a true Garden of Eden with fertile displays of ginger, vanilla, taro, noni and breadfruit. The medicinal and cosmetic benefits of the pants and flowers are well utilized by the Tahitians, renowned for their health, physical beauty and spiritual serenity.

For this final tour, my guide was an Euro-Tahitian anthropologist, who has lived in Tahiti Nui his entire adult life. While charging through the thick forested terrain in our jeep, he explained the intricacies of Tahitian culture, where the past meets the present, and that the Gallic texture of today is often only evident on the surface. The French police keep the islands safe but will never enter a home when there’s a family dispute or even violence. Often times when a local commits an egregious crime, justice is handled the tribal way, where the offender might ‘accidentally’ fall from the top of a mountain or ‘mysteriously’ drown while fishing.

When a Tahitian woman reaches the age to give childbirth, she is encouraged to take as many lovers as she chooses. When an infant is born, the child is given to a group of older women, often aunts (slang, motu mamas) to be raised by the community in wide open mountain valleys. From my guide’s studies, he believes that Tahiti and Polynesia illustrate the most tolerant and sophisticated child rearing practices in the world; a world where the youth find meaning through relationships with the family, community, spatial terrain, ancestral spirits and God.

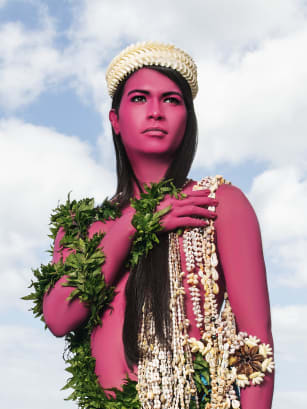

Māhū: French Polynesia’s Esteemed Third Gender People

A person referred to as a Māhū is a male born child, raised as a girl. When a young boy illustrates what is considered feminine qualities such as cooking, cleaning and sewing as opposed to the assumed male characteristics of hunting, fishing or going to war, he is simply raised alongside girls. There are no negative ramifications on being a Māhū, and the people are considered a culture-bound transsexuality treated with great respect. Māhūs traditionally play key social and spiritual roles, as guardians of cultural rituals and dances, or providers of care for children and elders. Many continue as Māhūs throughout their adult life, and once enjoyed the trusted status of servants to the royalty. The earliest known written reference to Māhū people was in 1789, when Captain Bligh of the Bounty wrote in his logbook about “people very common in Otaheitie called Mahoo… who although I was certain was a man, had great marks of effeminacy about him. They weren’t just tolerated, but embraced…”

“Māhūs have this other sense that men or women don’t have,” said Swiss-Guinean photographer NamsaLeuba, whose images from French Polynesia appeared at a recent exhibition in London. “It is well known that they have something special.”

My guide continued with an anecdote about a friend who was the father of three Māhū children. Though the man was proud of his offspring, he laughingly complained that he had no one to go fishing and hunting with. Some adult Māhūs become fathers — and this is the very essence of Tahiti, where virtually everything is embraced with an easy, no sweat mentality.

Marché de Papeete

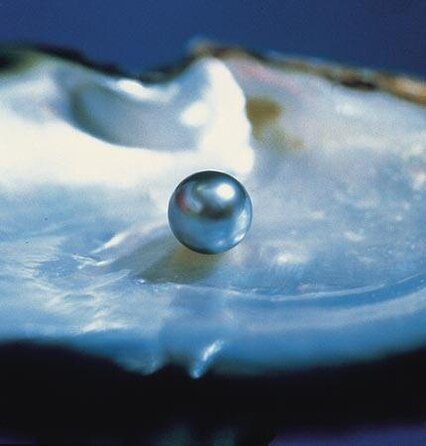

Spread over an entire city, the two-story Marché de Papeete has occupied the same location in the commercial center since 1869. It is nothing less than an institution and a must-see for every visitor. The first-floor features fruit, flowers and souvenirs to fresh seafood, produce and takeaway meals. I found that hand-painted pareus (sarongs) — worn by women and men alike — make an inexpensive gift to friends. The pearl typifies Tahiti — and also its leading export — and you’ll find large retailers selling a variety of Tahitian pearls, ranging from inexpensive to the opposite. On the market’s second floor, I made the bold decision not to dive into the water in search of a pearl for my bride’s wedding ring and managed to purchase one, a perfect black one with ease, despite my clumsy bargaining power.

Most importantly, Marché de Papeete is the ideal venue to kick back with a tropical smoothie, and watch merchants and local shoppers laugh, chat and talk story. There is no better place to enjoy the pulse of Tahitian city life.

MORE ON PEARLS

Rangiroa, located approximately one hour north of Tahiti Nui, is the world’s second largest atoll, i.e., a submerged volcano with only the motu (sandbank) at the water’s surface. Long considered the epidemy of an island paradise, scuba diving and pearl farming is Rangiroa most popular activity, with 240 small islets protecting the atoll’s infinitely deep lagoon.

The Robert Wan Pearl Museum, the world’s only museum dedicated exclusively to pearls, is a short stroll from the Marché de Papeete. Mr. Wan has devoted 51 years of his life to exploring the role of the pearl in art, history, and literature, and his exhibits reveal pearl farming techniques and why they are associated with religious rites and status symbols.

The museum also showcases the largest cultured Tahitian pearl in existence; the Robert WAN, which measures almost an inch in diameter. A guide informed me that the pearl is the world’s only gem born from a living being.

Yes, Tahiti Nui has much to offer, but locals also proudly tout the outlying, less-populated islands for their beauty and tranquility. Like southeast Alaska, exploring the other Tahitian islands is best accomplished by booking an excursion on a cruise ship. You get to see more islands and it’s less expensive.

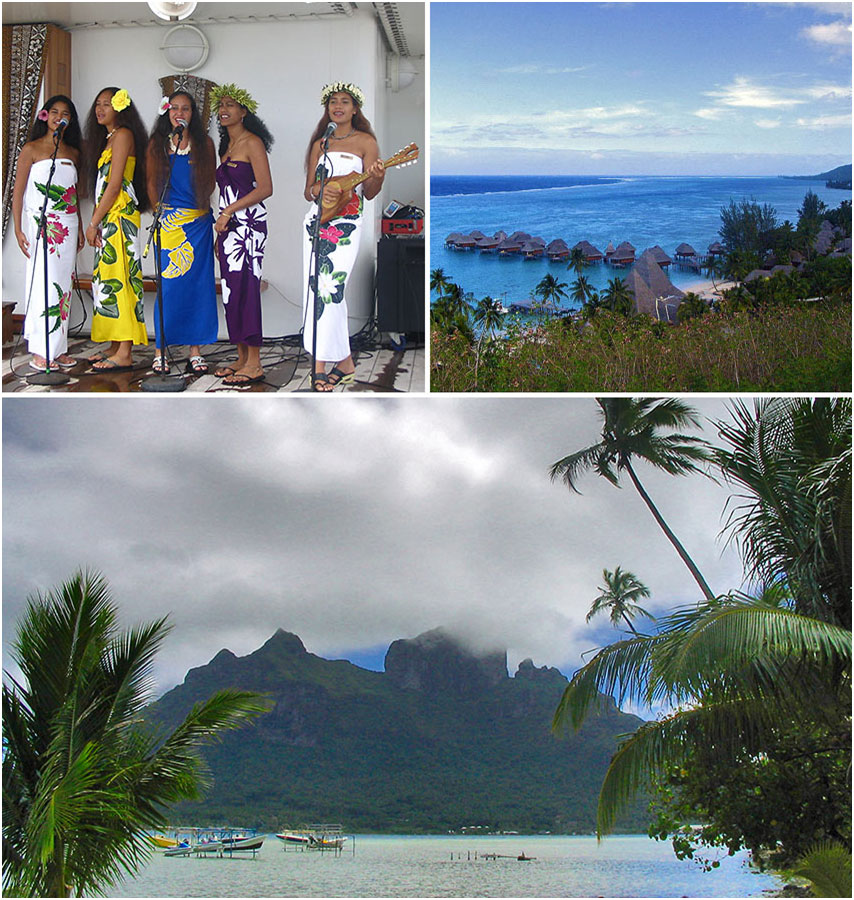

Bora Bora – The Romantic Island

As my helicopter soared over Bora Bora’s alluring blue lagoons and tropical slopes, my pilot said it was only the second time he had maned a ‘copter… that is, the second time today. After our nervous laughter subsided, Mount Otemanu soon loomed in the distance, and it became clear why this enchanting island is synonymous with romance. Bora Bora is ideal for a bike ride around the island, a leisurely hike, or to simply disappear by a refreshing lagoon. The history buff will enjoy seeing remnants of cannons manned by American servicemen during World War II. Until 1942, there were no roads and no vehicles on Bora Bora. Tourism, of course, is theme of the today with scores of tasteful, over-the-water bungalows dotting the seascape.

Moorea – The Magical Island

Moorea is a profound example of a south seas island paradise, and it comes as no surprise that it is a favorite of many Tahitians. The beauty of the island, with its jagged green mountains and palm-draped beaches, is astounding. James Michener called it Bali Hai, Herman Melville based his novel Omoo on it, and Captain Cook spoke passionately of its landscapes and the attractiveness of the people. Moorea is unique among the Tahitian Islands in having magnificent expanses of both white and black beaches, while in most islands it is the pristine lagoons that illustrates much of their ethereal characteristics. High in Moorea’s interior mountains, Polynesian royalty practiced their archery and constructed maraes hidden in rainforests. On a hilltop lookout between shark-tooth Mount Rotui and towering Mount Tohivea, there’s a once-in-a-lifetime view once reserved only for the gods.

Raiatea – The Sacred Island

Raiatea was the cultural, religious and royal heart of Polynesia — the birthplace of the gods. The second largest Tahitian isle, and where entire clans canoed off to find new homes on other islands. Today, you can paddle around Faaroa Bay and discover why the island was a favorite of Captain Cook.

Taha’a – The Vanilla Island

Taha’a offers a glimpse of the traditional tranquil life of Tahitians. The flower-shaped island is surrounded by tiny motus, and in its fertile valleys, farmers grow watermelon and vanilla — first cultivated in Mexico, but, for me, with a more delicious flavor.

The Food of Tahiti

Indigenous Tahitian cuisine uses what’s available from the land and the sea, and the word, ‘fresh’ is essential. The taro root (more flavorful than the Hawaiian version), breadfruit, sweet potatoes, and plantains offer typical starch fare. Mangoes, bananas, watermelon, pineapple, papaya, guava, soursop and pummelo are in abundance. From the lagoons come parrotfish, perch, and mullet; from the open sea, fresh tuna, bonito, wahoo, scad and mahi mahi. Coconut milk and vanilla are incorporated into many of the dishes. With Poisson Cru, a French hybrid of tuna cured in lime juice with chopped green onions, cucumbers and tomatoes; and Fafa, a chicken stew with taro leaves; my taste buds were seduced with remarkable new flavors.

Yet, as of today, McDonald’s has even made their presence felt with three franchises in Papeete. McBaguette, anyone? But, thankfully, Tahitian snack bars and food trucks (les roulettes) still reign supreme.

Tahiti & Her Islands: The C-19 Pandemic

Upon check-in at the airport, your airline will require proof of a negative COVID-19 test. The government of French Polynesia accepts an Antigen Test administered withing 48 hours of departure, or an “RT-PCR” Test administered within 72 hours of your international departure.

Today, Tahiti & Her Islands remains the definition of an enchanting island paradise, with the warmth and openness of its people the very essence of its charm and beauty.