Deep turquoise waters, ancient Andean cultures, breath-taking landscapes, and majestic 400 year old cathedrals make the region and city of Ayacucho one of Peru’s most interesting, yet least visited, tourist attractions.

Unfortunately, this unique region is known more as the birthplace of the terrorist organization Sendero Luminoso or Shining Path, who ruthlessly dominated the area in the 1980s and 90s, than for its astonishing history, culture and scenery.

With that said, today Ayacucho proves to be the perfect destination for tourists in search of a more local experience in the central highlands than might be found in larger sites like Cusco or Arequipa.

Brief History of the Shining Path

Winding up and up from the Pacific coast into the central highlands of Peru, one realizes how Ayacucho, a historically isolated and often forgotten region of Peru, became home to a tragic internal conflict which would eventually claim an estimated 69,000 lives between the years 1980 and 2000 (according to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission established by the Peruvian government).

In 1969, El Partido Comunista del Peru – Sendero Luminoso (Peruvian Communist Party – Shining Path) was founded by its leader Abimael Guzmán, a philosophy teacher at San Cristóbal of Huamanga University in Ayacucho. Guzmán, who became enamored by Maoist ideology, began introducing communism to his students and recruiting them for guerrilla warfare and cultural revolution.

In 1969, El Partido Comunista del Peru – Sendero Luminoso (Peruvian Communist Party – Shining Path) was founded by its leader Abimael Guzmán, a philosophy teacher at San Cristóbal of Huamanga University in Ayacucho. Guzmán, who became enamored by Maoist ideology, began introducing communism to his students and recruiting them for guerrilla warfare and cultural revolution.

The party, confined primarily to academic circles during the 1970s, began its attacks in 1980 by burning ballot boxes in a village near Ayacucho, attempting to stifle the country’s first attempt at democratic elections since 1964. Sadly, this attack was only the beginning of their reign of terror and a long, tragic period of violence in Peru.

While the government turned a blind eye for over a year, the party began brutal, coordinated attacks and assassinations on political leaders, labor unions, and other peasant organizations. They gathered support from primarily poor, rural areas where many only spoke Quechua, an indigenous language.

When in 1981 the Peruvian government finally declared a state of emergency, it would only complicate the situation for the people of Peru. The decree consequently gave the military unequivocal power to detain anyone under suspicion of terrorism, leading to an overall escalation of violence.

As the conflict grew stronger, local people found themselves trapped between a rock and a hard place, between the Peruvian military and the Shining Path, both sides guilty of intimidation, massacre, kidnapping, rape, and torture. A primary tactic of both groups was the kidnapping of men and boys. For the Shining Path, kidnapping served as a form of recruitment and social control. For the military, the tactic was used as “punishment” for political leaders or anyone else suspected of sympathizing with the Shining Path.

Not unlike most internal conflicts, civilians suffered the worst of the violence. Studies estimate that over 90% of deaths and disappearances were suffered by innocent townspeople who sided neither with the military nor the Shining Path. Out of all the victims, 4 out of every 10 were from the region of Ayacucho, 3 of every 4 were Quechua-speakers, and over half were farmers or shepherds.

In 1992, the Shining Path slowly began to collapse with greater pressure from the military and the capture of Abimael Guzmán, but it would be almost 10 more years before the party truly disintegrated into smaller, less influential groups.

Today, the people of Peru and especially Ayacucho remember these years with deep sadness and pain. They remember the anxiety of a time when no one could sleep peacefully, a time when fear ruled. They remember the government and international community turning a blind eye to their suffering. They remember fleeing to other regions and cities, leaving behind family, lands, and animals. Yet most importantly, they will always remember the thousands of people who were victims of violence, kidnapping, and murder.

Speaking with locals, I found that they want others to be educated about the evils that occurred, yet they no longer want their home to be defined by these experiences. Locals want their city and region to be remembered for what it offers, for the various pre-Incan cultures who ruled there, for their unique contributions to art and music, for the battle site where Peru won its independence, and for its kind and humble people.

Ayacucho Today

At 9,058 ft. (2,761 m.) above sea level, the Andean city of Ayacucho lies between rolling hills and farmlands. If you decide to brave the long, windy, 10 hour bus ride from Lima, you’ll experience firsthand the natural beauty and geographical isolation of the region.

Like many Peruvian cities, Ayacucho, a town of over 180,000 people, is quickly growing and houses continue to pop up on the surrounding hillsides. The tourist lookout, Mirador de Acuchimay, which was originally constructed at the edge of the city, now stands smack in the middle. As one local pointed out, you now have to turn 360° there to see the city in its entirety.

Inside the City

As you begin to explore the city, the central plaza (plaza de armas) is unavoidable. The colonial architecture, well-maintained gardens, and central statue resemble those of Cusco. But as one local proudly commented, “We should begin saying Cusco resembles Ayacucho, not the opposite,” believing Ayacucho was Peru’s true historical and cultural origin.

Entering the main cathedral dating back to 1672 is worth your time, and for a fee of 10 soles ($3) you can receive a tour of the museum and crypt and climb the bell tower for a wonderful view of the city and plaza. The museum is home to church artifacts as well as a Peruvian painting of the Lord’s Supper with traditional foods like guinea pig on the table. If you’re still interested afterwards in visiting more colonial churches, don’t worry. Sometimes known as the city of churches, Ayacucho has over 30 other cathedrals and chapels.

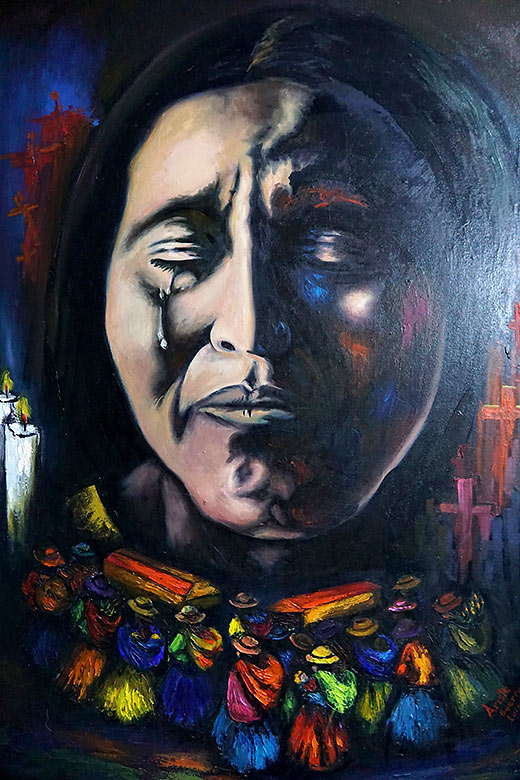

After exploring the plaza and city center, we took the short walk to “El Museo de la Memoria.” This small museum is dedicated to remembering the victims of violence during the 1980s and 90s and honoring the courage of those who fought for truth and justice. The chilling exhibit was created by ANFASEP, the organization which resisted violence and worked to locate and free missing or detained persons. Inside is a timeline of events, art dedicated to those who were lost, personal testimonies, and artifacts. The stories of everyday people who disappeared, their photos, and the absence they left behind are especially impactful.

From El Museo de la Memoria, it’s only a brief stroll to the Hipolito Unanue Museum where you’ll find artifacts such as art, weapons, and tools from various ancient cultures dating back hundreds or even thousands of years.

Ayacucho would not be complete without an appreciation of its unique art, especially ceramics and detailed wooden boxes called retablos. Art galleries are located throughout the city containing pieces depicting scenes from the Andean countryside, Catholic religion, or the period of violence. If you’re looking for a souvenir, make your way to the artisan market (Mercado de Artesanías) and find local artists selling their own work.

While in the city, be sure to try typical foods like mote (corn and tripe soup), cuy (guinea pig), alpaca steak, and most notably puca picante, a strikingly red, spicy dish made from a beets and peanut sauce. If you’re in the main plaza, grab a handmade ice cream called muyuchi or head to a Belgian-owned restaurant called ViaVia Café which serves a variety of dishes including quinoa and alpaca.

Day Trip Adventures

These light blue, naturally-forming pools outside Ayacucho have become a popular tourist destination ever since they were opened by locals a few years ago. Although a long drive (3.5 hours), the day trip is an opportunity to see the high altitude countryside dotted with wheat fields and wild agave and cactus.

Upon arrival, a short hike takes you up into the hills, and the view from 11,600 ft. above sea level is stunning. From above, a small stream becomes a waterfall and cuts through high rock walls where it settles into blue-colored pools. In the sunlight, an optical illusion makes the water appear turquoise due the presence of certain minerals. It’s a rare and beautiful site, and tours from the city (in Spanish) only cost around 80 PEN ($25).

While still under excavation, the Wari site provides a fascinating look into the customs and beliefs of one of Peru’s most powerful and widespread pre-Incan empires. Within the complex, you’ll discover ruins of a sacrificial altar, royal houses, burial and religious sites, and water systems.

The Inca were masters at adopting the best in art, science, and culture from each culture they conquered. It was no different with the Wari. Rock walls from late Wari culture are almost identical to Incan construction you’d see in Cusco, and their water systems are clear forerunners to those of their conquerors. As our guide shared with Ayacuchan pride, “Here we’ll see who actually learned from whom.”

In Quinoa, the heart of Ayacucho’s ceramic arts, you’ll see local artists at work and later peruse shops with a variety of handmade products. Just three minutes down the road is La Pampa de Ayaucho (The Plains of Ayacucho), where Peru won its final and decisive battle against the Spanish. An obelisk has been constructed in honor of the soldiers, and the high plain provides a spectacular view of the valley and city below. We found the trip to be worth our time and money, only costing 40 PEN ($12) for transportation and a guide.

Ayacuchan Pride

Throughout our visit, I enjoyed many conversations with locals and tour guides. As they shared their experiences, I felt both the sadness of their experiences as well as their hope and pride in their city and region.

On our last morning I took a walk into the plaza and was met by a familiar site here in Peru — a local parade. As always, the national anthem began the ceremony. But then I noted a significance difference. In place of the typical whispers and mumbles, I heard a roaring anthem. The lyrics seemed to rise from a place deep within each police officer, soldier, student, parent, and teacher. Perhaps it was a coincidence or maybe, just maybe, their voices represented a not-forgotten struggle against terror and a new-found freedom and peace.

Regardless, the words rang strong and true:

“Somos libres, séamoslo siempre…”

(We are free, may we always be so…)

“En su cima los Andes sostengan la bandera o pendón bicolor…”

(On its summit may the Andes sustain the two-color flag…)

“…a su sombra vivamos tranquilos”

(…under its shadow may we live in peace)

****Disclaimer: “The content of this website is mine alone and does not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Government, the Peace Corps, or the Peruvian Government.”