Dedicated to Richard Carroll – Who Inspired this Theme – Who are the most interesting, passionate, and memorable people you have ever met in your travels?

Jim Boitano: Meet Angela Biedermann – Photographer, Designer, Baltic Tour Guide Extraordinaire!

She isn’t famous, but I’ll never forget Angela Biedermann. On a six-hour bus ride across the flat Baltic countryside from Vilnius to Riga, I met her back in 2003. Just one of those people you run into when you travel and fall into deep conversations.

She was a Viennese photographer, well known in her small local circles in Austria for her beautiful art exhibitions. She was best known for taking shots of old Austro-Hungarian doorways, thresholds and house facades. She was recording these in the Baltics when I met her.

We all have encounters with interesting people when we travel, often on planes, sometimes on trains. But usually when we arrive at our destinations, we scatter to the four winds.

But Angela kept in touch. Every year for my birthday, she made me a personalized birthday card containing multiple examples of her work. She even designed her own postage stamps. As someone who doesn’t have that type of artistic gene, I appreciate it so much more when shared with others. Beyond that, she became a kind of pen pal and we would write each other long emails about our lives.

I went to visit Angela twice in Vienna. Of course, her apartment was a museum. She called it ‘my Moroccan Palace’ and indeed it was a shrine of art and décor. I helped her set up for one of her shows (on India) and got to attend it. This was in 2011 and again in 2014.

Last year, I received a letter from her sister advising me that Angela had passed away from a pulmonary embolism. She was 20 years older than me, and when I met her that seemed quite old. Now I’m older than her and she will continue to inspire me to travel and enjoy the art we find in the little places in this world.

Richard Carroll: So Many

I have met a number of memorable persons in my travels, many who have become life-long friends. Among them in no particular order are Tom McCarthey, who I met in Maui years ago and is passionate about life with a marvelous sense of humor, a world-wide traveler, and with a big heart.

Celia Abernethy, born and raised in the United States who fell madly in love with Italy, learned to speak Italian, and is now the supreme contact for travel to Italy. She has homes with her husband in Milano and Lake Como, is extremely knowledgeable about all aspects of Italy, and always with a smile on her lips.

I met “John Colclough” in Dublin some 30 years ago and we have remained the best of chums. John, with his thick Irish accent, a photographic memory, and splendid vocabulary, has spent a lifetime researching, traveling Ireland and collecting in-depth details, it seems, on every major building, castle, Townhouse, estate, and historic site, in the country, along with the family history of each.

Another memorable encounter was in Salt Lake City. I was not quite a teenager when I thought I could play the trumpet, and along with David Pratt, who played clarinet, we wanted to show our skills to the great “Louis Armstrong,” who was performing with his band in the evenings at the Rainbow Randevu in downtown Salt Lake.

My sister Sharon, pulling a little red wagon, and our family dog, followed us to the Hotel Newhouse. With our instruments in hand and a battered music stand we sneaked up to the second floor of the hotel and knocked on Louis Armstrong’s door. A nicely dressed man opened the door and coldly stared at us. Looking at our feet we said to him, “We want to play for Louis Armstrong.” He started to shut the door but Louis said, “Open the door and let them in.” Armstrong was sitting on a bed in shorts, and a gorgeous black woman wearing a sparkling gown with strands of gold chains dangling from her neck was standing near the door smiling at us.

He said, “Come in boys.” We quietly said, “Can we play a duet for you Mr. Armstrong, David wrote it.” The man who opened the door was now holding a telephone and kept repeating, “Louis, New York is calling again!” Louis, said, “Hold the call. I’m busy.” We set up the music stand knocking it to the floor twice.” My mouth was dry, hands were shaking, and with two false starts we sounded horrible. When we finally finished the duet, Louis said, “Keep up the good work boys. What mouthpiece are you using?” I said, “It’s a Bach 7C,” handing it to him. He gave us personalized autographs, and said, “If you ever come to New Orleans I would like to see you both.”

We packed up and left, while New York was calling. My sister greeted us on the street and said, “Did you play for Louie? I thought I heard something?” We said, “We did, but it wasn’t so good.” She said, “Will you play for him again.” Nodding our heads we said, “Never.”

Phil Marley: Peter Marley, My Father

Peter Marley, though he preferred to be called, “Pete,” was a Cockney Londoner, who was a boxer before joining the British Merchant Marines. One of the vessels took him to Winnipeg, where he met and married a 14-year-old Canadian farm girl, who gave birth to my brother and me.

When my family arrived from Canada, I was eleven-years-old, and was very naïve and ignorant of the ways of the world that day. So, my first memory was moving into a small apartment on Lower Queen Anne Hill. Eventually I would become a high school student on the top of its hill.

As we unloaded our baggage, though there wasn’t much, for the small apartment was fully furnished, I noticed there was a strange buzz in the air, unlike anything I had ever heard before.

Later, I learned it came from concert at the site of the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair, by a rock group from Liverpool, who had shockingly long hair. They were named the Beatles, and in a few years would have a great impact in my own life. Soon I transitioned to John Lennon government-issued horn-rimmed glasses and began to wear my hair long. I was also a fan of the Rolling Stones. Once, while chomping on a candy bar in my family’s car, my father said, “You keep that up, and you’re gonna rot your teeth out like that Keith Richard.” I smiled, and said: “Yeahhhhhhhhh!”

My father, Peter, found a graveyard position as a security guard in downtown Seattle’s new 50 Story Bank Building. We were proud of his new tenure, though others thought it was absurd to take pride in such a low profession. But we would remind them, it was an honest job, and he was in charge of protecting a high building, which was then the tallest throughout Seattle.

As I said, my father was a Cockney from London, and my brother and I would laugh when others could not understand what he was saying. And sometimes we would laugh at ourselves, too; for we couldn’t understand a single word he was saying either, and were given a one-way ticket to be alone in our bedroom on Queen Anne Hill.

In the early morning, around 6 a.m., his night of work was over, and he would pack our family in our family’s Studebaker for a trip to Seattle’s Green Lake.

And it was there that he taught me how to swim and dive. Due to the early morning hour, the area that surrounded Green Lake was empty of people, and we had the lake to ourselves. And I enjoyed the solitude, for no others would see me struggle and swim, and laugh at me as I crawled up to the shore.

Our high school was on the top of Queen Anne Hill, famous for its setting and spectacular city views. On clear days, we could see majestic Mt. Rainier.

But for us, Queen Anne High School was just an old building and we would barely notice the views.

But, we were only kids.

David Erskine: Peloponnese and Epiphanies, Greece

My name is David Erskine. Ed Boitano of Traveling Boy asked me to write a guest article, written just ten minutes north of the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco. I have been a Traveling Boy reader since the conception of the travel site, and also Vice President of Advertising from 2020 until the height of the Covid pandemic.

I recently spent over two weeks in Western Greece (the Peloponnese towns of Finikounda, Elafonisos and Monemvasia). It was a family reunion with the German and California families. It also was an opportunity to keep the European and American families connected, which was a request of my mother before she passed many years ago. Additionally, it was a way to honor a reunion from 1971 with my mother’s siblings in Germany and their children in Gmunden, Austria.

The theme for this travel article is Peloponnese and Epiphanies.

The request and legacy of my mother, who grew up in Dresden in the 1920s and 1930s is alive and well today. My German Uncle’s son and daughter attended the reunion and my cousin’s two grown children and my daughter as well. The legacy continues for another generation.

I share this as a foundation and backdrop to where the reunion took place for this article.

Traveling from San Francisco to Greece is a journey across ten time zones and here are a few takeaways and epiphanies.

Clarity: As I have been studying the ancient stoics and Eckert Tolle about being present it was becoming a mental exercise as I tried to undo the unconscious mind and become more conscious, i.e., living in the moment. Well, when I woke up the first night around three am and listened to the Ionian Sea outside my window, it dawned on me that I was present. Between the distance, lack of noise, TV or Internet, my mind was clear, and I was present. I was not worried or concerned about anything other than where I would run my miles the next morning.

History/Perspective: On June 4th, 2024, we walked the ruins in Messini circa 3 BCE. As an actor to walk in an amphitheater where actors walked the stage centuries ago or to see my daughter and her cousin walk in the sports arena where athletes competed so long ago literally took my breath away and gave perspective and context to my life and how living in the present and controlling what I can control and dismissing the rest is a gift.

Gratitude: Am so thankful for all the Greek people I met and shared a conversation, laughter and connectedness. I was recently reminded how important it is to bring joy to someone every day and perhaps a smile or a laugh. When all is said and done, remember: “And in the end the love you take is equal to the love you make.” – The Beatles.

David Erskine: World Traveler, Poet, Actor, Runner, Taxi-Driver, T-Boy Writer

Fyllis Hockman: What’s this – Ed Boitano?

Ed Boitano — because he has given us “Traveling Boy.”

Raoul Pascual: My most Travel Influencer

For me, the most influential person in regards to Travel would be Traveling Boy’s Ringo Boitano. I had known him early on as an editor for travel publishing companies but I didn’t expect him to be a walking encyclopedia about places to go, culinary delights, film and music of the 60s and 70s and geographic (mostly European) history. Ringo can spend hours sharing his anecdotes of just about anything.

Before I met Ringo, I remember I was touring a visitor to my hometown (back when I lived in Manila) and I brought him to different sites. Touring was simply “drive,” “look,” then drive to the next spot. I remember standing in front of the Intramuros (an antiquated Spanish fortress) in silence. Then he asked me, “So what’s the significance of this place?” And I was flustered because all that I knew about it was one sentence long. It was then that I realized the importance of knowing how things came to be — why was a Spanish fortress sitting in the middle of a grassy golf course far away from the shoreline? I wasn’t able to convey that this 300-year-old fortress is surrounded by reclaimed land and that it housed the prison cell of our National Hero who chose to die of a firing squad rather than deny his love for his country.

Historical facts are good but it lacks the joy and wonderment of a traveler-storyteller like Ringo. The way Ringo relates his adventures and the research he digs up makes me appreciate history then and history as it unfolds to the present.

Ed Boitano: MY PARENTS – Louis and Carol Boitano

My father, Louis Boitano, born Luigi Boitano on April 16, 1924, in Ballard, Washington, before it was incorporated into the city of Seattle. He taught me many things which I try to live by today: never judge someone about the money they make in an honest profession; be wary of flag wavers, they’ve probably never experienced a real battle; never define anyone by their religion or by the pigmentation in their skin color. And, never sprinkle grated Parmigiano-Reggiano on ravioli, for it interferes with the dish’s real natural flavor.

Luigi Boitano was mocked his entire life because he was a Roman Catholic and an Italian-American sinner. My father became the first Italian-American firefighter in Seattle. On his day of enrollment there was the customary pomp and circumstance celebration. But, he knew it was not for him; only for the new “white” recruits. The Fire Chief brushed past my dad: “Boitano, did you bring your stiletto?”

Once, when he was running too fast, he jumped on the back of a Fire Engine; he lost his balance and took a serious spill. He could no longer work saving people’s lives anymore. He was saved by his membership in the Seattle Firefighter’s Union. And, it was due to the Seattle Firefighter’s Union, that my family was saved from poverty.

At the time of his death, my family faced persecution from people who would mock Unions, which they considered to be Communist. Imagine, my father was willing to sacrfice his own life in WW II so these people would have the freedom to laugh at Unions — and, it’s due to Unions that we are not a Communist nation.

When I informed my father that I was planning to move to Hollywood, he said it was ok if I changed my family name to an Anglo-Saxon one. I asked my mother, why I was given the first name, “Edward?” She said, it was my dad who suggested it, so it would protect me from the hatred of White Nationalists who would be intimidated by the name of an English King.

Once, when he taught me how to drive a car, he said, “Ed, when you drive too fast… all you have to do… is take your foot off the gas.” As I grew older, I realized this was an important metaphor on how I should live my own life: “Never charge at the enemy looking for a fight, withdraw and no one will get hurt… no matter how much they had hurt you in the past.” Twice, a distant relative of my wife challenged me to a fight. But, I rememeber my father’s words. So, I took my foot off the gas… and no one got hurt.

My father was fearless and strong. After a long day of work at the Seattle Fire Department’s Engine 20, or after night shifts of labor at one of his two part-time jobs, he was never too busy to play catch with me or treat me to a Seattle Totem’s hockey game or a Seattle Rainier’s baseball game. He never once missed any of my little league baseball games on Magnolia Field. Once, when I was drafted into the majors at eleven-years-old, we looked down at Ray Field together from his old Volkswagen Bus. We saw our Magnolia All Star Players who were two years older than me. His own sense of worryness was greater than mine; “I was a Little Guy, playing with the Big Guys, who used to chase me around the block.”

Many of our summers were spent in Washington State’s Lake Roesiger in a cabin he built with his own hands. This was the place for great family reunions where everyone was invited: my mother’s church friends who she had known since she was seven-years-old in Sunday School, Italian and Scandinavian-American relatives, African and Asian-American inn-laws, and generally a new and lonely neighborhood boy who had no friends. Each morning would begin with my mother’s fried bacon, cooked on a woodburing stove. Then a big group would assemble around our large dining table to wait for my mother’s real specialty: “Hot Cakes!” smothered with real butter and my Grandma Nonna’s handmade jam, picked with berries from her own garden.

It was during one of our family occassions, later in the day, my parents helped me conquer my fear of water, and I learned how to water ski.

My mother once said that carrying my father’s Cross of Unhealed Pain was too much for her to carry alone. She asked God that she wanted a foul ball at a Rainier’s ball game to strike her in the forehead, so he would take her to heaven early. But, God said there was much more work for her to do. I was too self-centered to notice. All I asked God for was that the Rainiers make a double play.

I know we’ve all been persecuted some way or other. But I only think of myself. My mother-in-law, my beautiful Mother Gay, survived the Nazi occupation of The Netherlands, the Great Depression and the Winter Hunger. But, I never once ever heard her complain about anything at all. She would only speak with joy when starving people staggered to her self-sufficient family farm from Amsterdam to be fed. The only way these “City People” could survive was to dig up rotten tulip bulbs; and many of them had died because the bulbs were too soiled with disease.

Mother Gay and her Dutch Family were feeding “liberal urban elitists.” It’s such a “hateful” expression. My wife is frequently mocked with that same dogmatic expression. She is wounded and haunted by it. But, there is really nothing else we can do…

When my father first flew to Italy to meet our Italian relatives, it was the first time he could embrace his uncles and aunts and cousins; his relatives that his mother had told him stories about his entire life. When he returned back home to Seattle, he said: “This is the first time I ever felt I belonged.”

Louis, spoken correctly as Louie in French, joined the US Marine Corp when he was seventeen. He was involved in the Pacific campaign, a participant in D-Day: The Battle of Iwo Jima, and D-Day: The Battle of Okinawa. As a young child who loved playing army games, I would frequently ask him what his battle experiences were like. Yes, I was far too young to realize the pain my questions may have caused him.

My father, though, was not the type of person to shy away from any question, in particular, when it was from one of his own children.

With little fanfare, he would deliver a short narrative without any form of glory; but would always end with a valuable moral lesson:

“Eddie, no one really wins in war. It’s only the little guy who gets hurt.”

“But, Dad, didn’t you capture some real Japanese solders?”

“The Japanese were tough soldiers. Others in my platoon would try to break them in interrogation, but they would never break… they were tougher and better fighters than we were. You know, Eddie, the Japanese soldiers were ‘little guys,’ too, and they loved their families just like you do.”

My father spent the first years of his youth (two thru six) alone in a one-room migrant shack with his Italian immigrant mother, Adelina (My Nonna, MY Grandma Nonna!) who did not speak English. They survived by working in the fields of the Puyallup Valley in Washington State. Many blasphemous Luther ans and “inauthentic” Evangelical Christians — thank you, Pastor Chuck, for explaining this to all of us!– had called my grandmother and father criminals when they toiled in hard labor throughout dawn until the harsh darkness of a Washington rainy night. It was the only way they would not face starvation and experience God’s Salvation. Their shack had no indoor running water and one harsh lightbulb. I was unaware of this narrative until my early twenties, when I overheard my father speak to a kind woman at a small family gathering who was curious why he knew so much about the Puyallup Valley.

He conveyed his backstory above, without any sense of self-pity.

Kind Woman: “Louie, I didn’t realize you were so poor.”

My Father: “We weren’t poor.. at least we didn’t think we were. We always knew there was someone out there… who had it worse than we did.”

My beautiful Italian Grandmother, my beautiful Italian Nonna, was made fun of throughout her life in the US. She was branded as illiterate, because she could only speak broken English. Ten years before Nonna’s passing; I once sat alone with her in her small, dark living room in Ballard. And, she recited the Gettysburg Address and the Declaration of Independence in perfect American English. She always played by the rules in her new home in Seattle.

When my father, was close to death, my wife’s brother and her nephew, hurried over to his his assisted living memory care facility to say goodbye. No one had informed them of this, but they knew this in their real Christian Hearts, that God had told them that they must.

After they performed their eulogy, my father, Luigi Boitano, gently drifted up to heaven. And now, he rests with the Lord, who protects him from all the pain which may have come to my own family.

And, I must say, the pain in which I have caused him, too. Forgive me, Dad. I really did Love YOU.

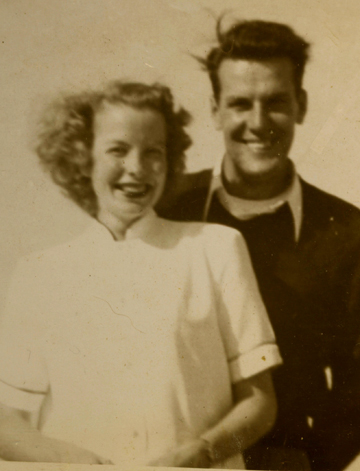

Carol Virginia (nee Stave) Boitano was given birth on December 25, 1927 in Washington State. Her parents had planned to name her Helen. But, when she was born on Christmas Day, she became everyone’s “Christmas Carol.” My mother and sister and mother-in-law all had/have beautiful red hair. But, my mother and mother-in-law were mocked throughout most of her lives for having it. When my father first met his soon-to-be-wed bride, he said it was one of the most beautiful visions he had ever seen in his life. Later, my wife’s Father Herman, later said something similar — when he first noticed a shy, young red headed woman, trying to hide in the background of her Dutch immigrant family — her etherial red hair, made him believe that God had sent her to be his eternal bride. Later, Father Herman wed this shy, young red headed woman, and she became my second mother, my Mother Gay.

I still don’t understand why Anti-Christians said the color of red was the symbol of the Devil. They’ve caused suffering to all of God’s children, just because he made them look a little differently than you.

So, my mother referred to her hair color as “Strawberry Blonde.” But, she never once dyed her hair to a different color. I think, my Mother Gay, only did to preserve her natural hair color of red.

Carol Boitano’s Scandinavian-American parents, Tom & Clara (Nee Hildahl) Stave and her siblings temporarily relocated to Burlington, WA to be closer to their extended families, before returning to Seattle’s Norwegian and Icelandic immigrant district of Ballard. My father would say, “And I had to marry the only Scandinavian who did not like fish.”

My mom grew up with a lot of good natured teasing from her siblings (five brothers). Her Stave family home was just a few doors down from my father’s residence, where he lived with his mother, Adelina (my beautiful Italian Nonna), stepfather “Johnny,” and half-brother, Aldo. My mother would often ask her younger brother, Stan (who currently lives in an assisted living home in Seattle) to play tennis on the street which faced my father’s home, so that he would notice her. But, it was not necessary for he had often secretly basked in her beauty many times before.

They were Ballard’s Romeo and Juliet, who lived across the street from one another. At first my father was too shy to ask her on a date. He feared that she would condemn him as an anti-Christian Roman Catholic, just as her own father (my grandfather Stave) did when my father asked for her hand in marriage. My “Christian Lutheran Grandfather” made him swear that his first child must be raised as a Lutheran. Grandfather Stave was completely blinded by the German Roman Catholic Monk, Martin Luther, that he actually believed Luther’s inflammatory book about why we should persecute Germans of Jewish ancestry: “On the Jews and their Lies.”

Louie kept his vow, and that is why I’m a Presbyterian — but, not a Lutheran. The Presbyterian Church is often considered the most liberal branch of the Protestant Church. It was the only way my mother could heal her father of his sins which he had commited to her husband, my Father Luigi. I recall, I once sat through a service at my Presbyterian Church. The minister was a devout African-American Christian, yet there were no other African-Americans in attendance. I’ve read that Africans were God’s first and most favored people in his own Kingdom. Yet, over 114 million Africans perished due to blasemous Christian white slave traders. And, today, White Nationalists scream, why must there be such a hateful thing, called BLACK LIVES MATTER? Why do they riot? We give them free food and small rent-free apartments. I think the answer is obvious. Violence is the only answer that White Nationalists can truly understand.

My mom was an early version of Traveling Boy’s Fyllis Hockman and my wife, Deb; where she would politely correct me when I miss pronounced a word, but did it in a way which would not upset me. She also typed and proof read four of my screenplays.

My mother was once an executive at AT&T Phone Company in Seattle. One of her clients was our greatest city father, Ivar Haglund (“Keep Clam, Keep Calm!”). My mother said when she would call him, he would begin with one of his corny jokes, but those jokes were the reason why she loved him. Ivar Haglund: the son of two poor Scandinavian immigrants; Seattle folk singer, restaurateur and the founder of Ivar’s Acres of Clams, his flagship restaurant on Seattle’s waterfront.

Seattle’s Smith Tower was once the tallest building west of the Mississippi. When Ivar heard it was for sale, he immediately paid a million dollars to purchase it. He really didn’t know what he would do with it; he just wanted to make sure a big corporation would not tear down one of Seattle most iconic landmarks. At this point, Ivar was growing older and knew he would not live forever. So, when he signed the contract, he entered a clause that the next buyer could not tear it down.

Starting in July of 1968, Seattle’s skyline would light up with a display of Fourth of July fireworks. I would watch them with my family on Magnolia Bridge. My mother would turn to me, “This is a gift from Ivar, honey. He’s paying for it.”

Before my mother passed away at the same assisted living memory care facility where my father had lived. She was demented to the point of blindness and could no longer speak. My wife urged me to take the first flight to Seattle to be with her.

When I arrived, her eyes were closed as she rested in bed. The room was dark. And, I was stunned by how much my beautiful mother with strawberry blonde hair had aged. I did my best to emulate how my wife’s brother and nephew had eulogized my father.

I stroked her hair and said…

“Mommy, this is Eddie… soon you’ll be in heaven with all the people who love you.”

I was surprised when my mother spoke. But, was not surprised by her last words…

I LOVE IT…

Yes, She LOVED IT.

God Bless You, Mom!

Skip Kaltenheuser: Rick Cluchey; Actor – Playwright, Boxer, Convict, an Inspiration

Once it sufficed a teenager to dangle from a water tower in high wind by as few fingers as would support the weight, or to jump a strange horse to see how long until he was rid of you. Or to ask out a girl that held one in a state of pronounced intimidation. A mere smooch was a victory of acceptance, “safe sex” a distant dream of Nirvana.

Collisions with alcohol could go many ways. The sting of tequila might be so bad the stench would warn you off for years. Life did not lack for hazards, but the risks seemed cleanly cut.

Now someone has mined the field of play. Young people are being devastated by crack, AIDS and triple-threat pregnancies.

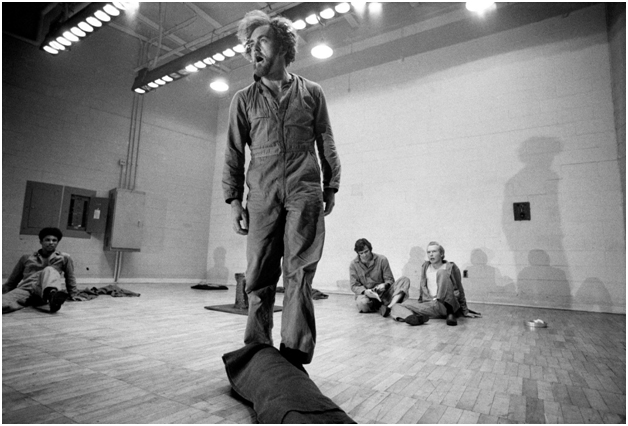

At Prince George’s Publick Playhouse, this Wednesday through Saturday, Rick Cluchey and the latest hybrid of his San Quentin Drama Workshop will seek to make these horrors imaginable when it presents “The Shepherd’s Song.”

The Publick Playhouse, formerly the Cheverly Cinema, is a facility of the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission. The theater is located in an area of the county that has a high incidence of substance abuse and positive testing of the HIV virus among teenagers.

“The whole thing is about intervention, catching people at an early enough age,” says Cluchey of “The Shepherd’s Song.” “This is the heart and soul of it. We have to continue to intervene and educate at younger levels.” Efforts are being made by county officials to bring residents of juvenile detention centers, as well as teenagers loosely defined by their schools as “youth at risk,” to the performances. “The people I do business with can’t afford a ticket to Arena {which recently staged “When It Hits Home,” a play about AIDS}, or other name stages,” says Cluchey. “They can’t read or write. Education is a high-sounding thing but to people who can’t read or write conventional education means nothing. You have to engage them on an emotional level and you have to engage them where they live.”

According to Cecil Thompson, theater specialist for Prince George’s County Department of Parks and Recreation and executive producer of the play, “County officials are alarmed and know they have to get the word out, and there’s no time for fooling around. The fastest growing population segment at risk is females age 14 and up. Consider that the average age of a female parent of an incoming kindergarten kid in Baltimore City is 20, and you sense the magnitude of exploding tragedy.”

“This production,” Thompson says, “represents attempts to focus public funds on major problems at a time of severe fiscal restraint. I hope Cluchey’s vision can be realized, to create good shepherds teaching both wellness for the stricken, and prevention — some hope beyond the pipe.”

The social utility of theater is what Cluchey, a resident of Silver Spring, is about. He came to the stage later than most professionals. Rather, the stage came to him. His first theatrical experience, at age 23, was a 1957 performance of Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot” in San Quentin prison. Cluchey was in the audience.

His crime career was brief, but if the prosecutor had gotten his way, the only notices we’d have read of Rick Cluchey would have been his execution.

The robbery was a day after a payroll delivery. A gun fired accidentally, and a ricocheting bullet gave a slight wound to the courier while he was held captive in his moving car. Under California’s “little Lindbergh law,” this qualified Cluchey for the death penalty. The judge, however, sentenced Cluchey to life without parole.

Though punctuated by success as a middle-weight boxer, life was bleak. “Then I saw myself on that stage, amid the two tramps commenting, and the baronial character hauling another guy with a rope around his neck.” Something sparked. One result was the San Quentin Drama Workshop, familiar to some from the film “Weeds,” in which Cluchey was portrayed by Nick Nolte. On his last day in office, Gov. Pat Brown made possible the reversal of fortune that put Cluchey over the wall after 12 years. After 10 years on parole, he was pardoned by Califonia Gov. Jerry Brown.

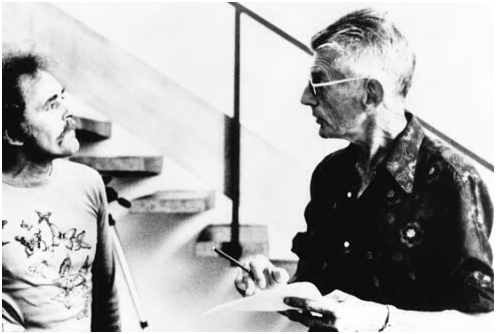

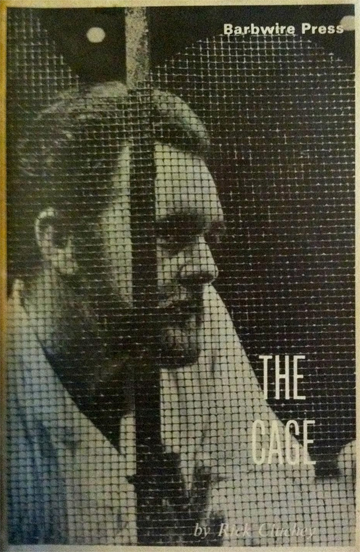

In prison, Cluchey wrote “The Cage,” which he eventually directed and performed in on Broadway, after warming it up at the Arena Stage. While performing in Europe, he hooked up with Beckett, who became his friend and mentor, training Cluchey to become a world-renowned interpreter of his works. Cluchey’s merit badges include an Obie for David Mamet’s “Edmond.” He was the first American actor ever to win the Italian theater critics’ Premio Critica, and has two Los Angeles Dramalogue Critic’s awards in writing, directing and acting.

Beckett’s influence runs throughout Cluchey’s approach to theater, and to experiments like the “Shepherd’s Song.” “Beckett was a spiritual man with an Irish sense of humor who carried deep pain from his identification with the harsher events in the world. He was not a nihilist, but a minimalist — poetic vision distilled to the last drop,” says Cluchey. “Beckett lived above a French prison, watching inmates signal him with mirrors. He was fascinated by prisons, mental hospitals, all the so-called bleeding meat of society. When he got the Nobel Prize, it was for demonstrating to humanity its pain in a way it could be understood.”

This is the challenge of “The Shepherd’s Song,” conveying understanding to generations that include many who are functionally illiterate. Says Cluchey: “They reject the messages sent by teachers they see as boors, their defense mechanisms are up to those approaches and they reject the ideas. We have to find a vocabulary to think the issues through, an architecture of thought and image that makes people understand the dues of irresponsibility, yet provides them with a voice so they know they are counted.” The message to the public at large is a stark one: Find ways to catch people who are falling or go down with them.

These thoughts are echoed by members of the multiracial cast, who range in age from 17 to 28. Ezra Knight plays the shepherd who counsels the teenagers as they confront their various fates in a juvenile detention center. Knight has worked for eight years with Arena’s Living Stage projects to reach young people in trouble. In response to a query as to whether the grim realities of the play are too unrelenting, he responds, “We’re used to people getting through, happy endings, so forth, but it is also important to show worlds we need to change. … In terms of the relationship of AIDS, crack and pregnancy, there is no better vehicle than this, with characters who speak a language that provides a bridge. It is incumbent for the audience to take that message and do something with it, not just sit on their butts and be gratified.”

With only six weeks to put the project together, Hayes Award-winning director Roberta Gasbarre required the cast to immerse themselves in the topics, attending presentations by Whitman Walker Clinic and getting tested, reading five new articles or pamphlets a night on the topics portrayed, visiting prisons.

All the while, she has done that delicate dance in line cuts that can make a playwright’s ears quiver, fitting the lines and rhythm to the stage choreography she envisions as most effective for the target audience.

“Kids have been talked at too much,” says Gasbarre. “They only listen to each other, only live in half-truths, and half-truths can kill them. I hope this will evolve into a national project that goes everywhere, including the prisons.”

Lory Fields plays Baby, a pregnant and homeless 15-year-old from a rural town in Georgia. Fields had previously done volunteer work in shelters and soup kitchens, but has found her empathy greatly stretched by her experience with the play, her first nonmusical role. “The play is challenging to the cast,” she says, “the idea of part of the audience living out what we are trying to portray. Hopefully by the time they’re adults these topics won’t be so taboo.

“We’ve had to become quasi-expert so we can handle questions in the informal forums that follow each performance. Our daily assignments include bringing in the latest slang, and the cast goes over each line to see what rings true. The sets, the lighting, the sound, everything will happen for a purpose. If they don’t understand everything we’re saying, they’ll understand what we’re feeling. The final performance will be signed for the hearing impaired, a real challenge of the craft. The issues are so far-reaching. It’s not just drugs that threaten. You can catch AIDS by sharing needles to pierce ears, or inject steroids, or from an elementary school blood-brother bonding. One of the toughest is curbing the negative feelings toward safe sex by teenagers who figure they’re charmed.”

The play has a consultant who has AIDS and who wishes to remain anonymous. He participated in initial readings at four Maryland juvenile detention centers last summer, but the evening of the last performance, he was rushed to the hospital with a 105-degree fever. “I’m still helping because I love kids, and they’re being stricken along with everyone else,” he says.

Meanwhile Cluchey hopes “The Shepherd’s Song,” a pilot play in continual progress, will become a national model. He says his San Quentin Drama Workshop has been approached by representatives of the National Commission on Correctional Medicine to put on the play at the commission’s September convention in San Antonio.

For now, the workshop is trying to generate enough community awareness to help raise funds to allow ongoing projects — such as the potential use of the auditorium at Prince George’s County Hospital for regular presentations in a medical environment.

“There is a strong link between substance abuse and risk behavior,” says Cluchey. “The message is: Don’t do drugs that diminish your capacity for judgment or you’ll do something dumb — fail to practice safe sex. If you have screwed up and contracted the disease, your days are numbered. But you can practice wellness that will increase your life span and shepherd those around you to protect them.

“We are heading into that intersection where theater and life converge,” Cluchey continues. “We’re using a Brechtian model in the dramatic telling of the lives of five young people, a cathartic story-telling of insoluble social problems, the warning finger that also points toward a redemption, a practicing of wellness and a stewardship of one’s fellows. What will not be confusing is the message of this play.”

Cluchey considers formats of communication that might counter the impact of crack, “a deadly drug tied to a deadlier disease, breaking everything apart inside, like a centrifuge, the fast ride and the sudden stop. These kids skipped right through the so-called gateway drugs like pot and booze that gave some warning perspective, and they don’t know what hit them.”

It all could make one long for the days when hanging from a water tower was a kick that lasted all day, like the memory of a first kiss.

For time context, my text is taken from a WaPo article I wrote in March, 1991. Rick became one of my closest confidants. Gone now, alas.

But his steady instruction, “Keep punching!”, still echoes.