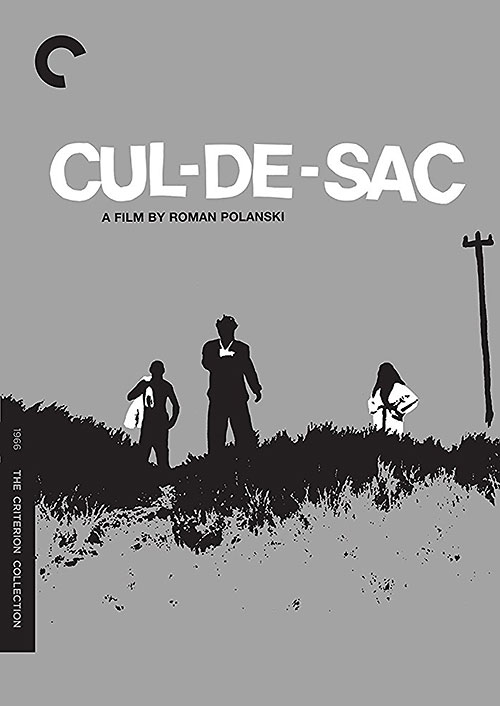

Director: Roman Polanski

Director: Roman Polanski

Writers: Roman Polanski (original screenplay), Gérard Brach (original screenplay) (as Gerard Brach)

Cinematography: Gilbert Taylor

Music: Krzysztof Komeda

Stars: Donald Pleasence, Françoise Dorléac, Lionel Stander, Jack MacGowran, Jacqueline Bisset (as Jackie Bisset)

Polanski’s “Cul-de-Sac”

By Walt Mundkowsky

(mostly written in London, 1969)

By this viewer’s idiosyncratic standards, Cul-de-Sac (1966) is Roman Polanski’s sole brush with greatness, and the only feature to keep faith with the surrealist metaphors and perceptions of his celebrated short films. It’s his most bizarrely funny, as well as his most serious work.

Cul-de-Sac takes a Desperate Hours-style situation (criminals on the run invade a normal household) and turns it on its head. George is a fiftyish English factory owner who has sold his business and retired to a fortress-like structure on Lindisfarne, a barren island (except at low tide) off the Northumberland coast. Teresa, his young French wife of a few months, busies herself homebrewing vodka, raising chickens, and advertising her sexual wares to passing males. Into this amalgam of character and landscape come Dicky and Albert, two gangsters wounded in a bungled robbery attempt. This quartet is reduced to a trio when Albert dies during the night. Dicky waits for Katelbach, his boss, to mount a rescue, but it never happens. The accumulated tensions heighten as a party of George’s former associates drops by unannounced. After George forces them off his property, Dicky calls Katelbach again and realizes that he’s been abandoned.

Polanski is here much influenced by the Theatre of the Absurd. Indeed, the proceedings might be profitably described as a cast of Ionesco characters, their outrageous humors and quirks on parade, playing at Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. The shifting power alliances among this trio are pitilessly observed; more pessimistic still is the sense that each of them is a solitary planet incapable of contacting the others, obeying physical laws they comprehend only fleetingly.

This is by several miles Polanski’s most ambitious and singular directing achievement. His unnerving use of the setting’s potential for entrapment, his instinct for the detail that clinches a line of development, his restless but purposeful editing touch — all these cohere into a moral argument presented in scathing terms. And Krzysztof Komeda’s off-kilter jazz is itself almost an individual personage — catchily melodic, texturally grating.

The lead performances are as much a triumph of casting as of directing; they reinforce Polanski’s view of human nature by having virtually nothing to do with each other. Donald Pleasance’s George is a career best, and somewhat related to his brilliant Davies in Harold Pinter’s play The Caretaker. In both we are invited to see the desperation lurking beneath the character’s picky, hectoring surface. Pleasance’s skill at shifting in mid-syllable from a command to a confession still astounds. Teresa is a nearly unactable monster as written — conniving, dishonest, juvenile. Françoise Dorléac (older sister of Catherine Deneuve, and tragically dead in an auto accident the following year) at least gives her a coquettish playfulness that renders the extravagances bearable. Lionel Stander has less operating room than they do, by Polanski’s design. Dicky is a none-too-bright career criminal and a blustering brute besides, but he’s the sanest of this unholy threesome. Stander delivers the primary tones unfailingly. Jack MacGowran, one of Samuel Beckett’s prized performers, makes the most of Albert’s deathbed scene. The young Jacqueline Bisset (billed as Jackie Bisset) is a sharp and snotty delight as the guest who notices too much.

An account of Dorléac’s death figures in Derek Marlowe’s novel Echoes of Celandine (1970, The Viking Press, Inc.) —

“On one page, her face stares out at me (beautiful, alert, almost boyish …). It is the face non-Europeans neither produce nor ever appreciate. It is too strong and yet fragile, too independent, too revealing — not only of the owner but also of the onlooker — and too defiantly feminine. (…) she out-Eves Eve in expression alone. If her body has been left to medical science, her eyes, at least, ought to have been left to Tiffany’s.

“I make a note of the actress’s name and attempt to tear the photograph from the magazine, but it is stapled badly, the picture tears, and I am left with half her face in my hand (right eye, a triangle of soft rain of hair, the crescent shadow of a cheekbone) and so drop the magazine, reluctantly, in pieces, on to the floor.

“It is not my night.”

(p. 91)

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.