The Addiction (1995) is the most stringent product of director Abel Ferrara’s current manner — a highly original morality play about guilt and redemption.

Red Sun — A Look Back

Terence Young is a moderately skillful Englishman who keeps laboring away at the action thriller, always with less than satisfying results. His three Bond pictures (Doctor No, From Russia with Love, Thunderball) had barely an atom of personality, and it would be charitable to describe The Poppy Is Also a Flower and Triple Cross as mediocre.

Ghost in the Shell (GitS) 1995 – A Look Back at the Classic Film

Mamoru Oshii's feature-length Ghost in the Shell beckons for relevance: Original title was Kôkaku Kidôtai (Man-Machine Interface) — my own computer battleground in the past two weeks!

Global Holiday Traditions, ‘Roma,’ Beatle Trivia

In Colonial America, Christmas was essentially a day of Spiritual observance. Carols were sung and church bells rang out to celebrate the commemoration of Christ’s birth. Early Americans decorated evergreen trees with things from nature and homemade items... The film ‘Roma’ is named Best Picture by the New York Film Critics Circle.

Richard Stanley’s “Hardware” – A Look Back at the Classic Film

For the young filmmaker with a music-video past and large aspirations, sci-fi horror can represent fertile ground. Narrative logic makes minimal demands, while extravagant style and pop nihilism are granted a prominence the mainstream denies. Richard Stanley’s ferociously effective Hardware (1990) was shot almost entirely on a single set for a meager $1.5 million; under its required elements, it fairly bursts with attitude.

Melville’s Le samouraï – A Look Back at the Classic French Noir

French filmmaker Jean-Pierre Melville (1917-73) is hard to pigeonhole. He operated outside established channels (eventually running his own studio) yet he employed movie stars. An inspiration to the New Wavers who liberated French cinema, he remained a consciously classical technician. Abroad he’s best remembered for a trilogy of gangster dramas — Le doulos (1962), Le deuxième souffle (1966) and Le samouraï (1967).

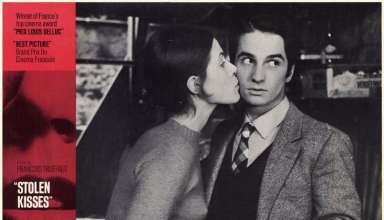

François Truffaut’s “Stolen Kisses” – A Look Back

In The 400 Blows Truffaut introduced Antoine, a 12-year-old at odds with the world in which he found himself. Antoine lost his girlfriend to an older and more masterful rival in the opening segment of Love at Twenty. Now, after two failures (not only of execution), Truffaut has returned to that character, but Stolen Kisses does not mark a reprise of his most confident style.

Polanski’s “Cul-de-Sac”

By this viewer’s idiosyncratic standards, Cul-de-Sac (1966) is Roman Polanski’s sole brush with greatness, and the only feature to keep faith with the surrealist metaphors and perceptions of his celebrated short films. It’s his most bizarrely funny, as well as his most serious work.

Johnny Got His Gun – A Look Back

The praise that has rained on Dalton Trumbo’s Johnny Got His Gun has a desperate ring, citing it with All Quiet on the Western Front and La Grande Illusion in the roll call of antiwar classics. Trumbo, of course, was one of the Hollywood Ten, refusing to cooperate with the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1947 and eventually imprisoned for 10 months for contempt of Congress.

Z – A Look Back

Costa-Gavras’ Z predisposes one to admire it, as the first film to indict the brutal military regime in Greece; in fact, the music by the long-imprisoned Mikis Theodorakis had to be smuggled out of the country. From the bitter opening title card (“Any similarity to actual events, or persons living or dead is not coincidental. It is intentional”) our sympathies are engaged.