“The professional art dealer is a profession that only makes sense if you do it with your heart,” explains Angela Rosengart, as she leads me through the ground floor of the collection that bears her name. She wears a pink sweater highlighted by a necklace of gold-colored pedants. Her silvery hair is tied back tight around her head. Speaking from half a century of art acquisitions, she continues, adding that a dealer shouldn’t get too attached to the paintings. If that happens, you’re in trouble, since you might find it difficult to sell them and maintain the business.

Angela is the daughter of Siegfried Rosengart, who passed away in 1985 after a lucrative career as one of the 20th century’s most distinguished art dealers. Based in Lucerne, Switzerland, he and Angela operated the business together for decades, often purchasing works for their own personal appreciation rather than for any intention of moving them as product. In the process of becoming close friends with Pablo Picasso, Marc Chagall, Paul Klee and nearly every high-profile European artist from the 1940s onward, the Rosengarts amassed an unrivaled collection. As dealers, they knew everyone.

After her father died, Angela eventually created a foundation to keep the paintings and make them publicly available. Since 2002, the Rosengart Collection, now over 300 works, has occupied the austere neoclassical building at Pilatusstrasse 10 in Lucerne, formerly the Swiss National Bank, just a few blocks from where the Reuss River flows into the lake. Upon acquiring the old place, Angela hired the Basel-based architect Roger Diener to transform the building into a museum-style structure with subtle lighting and wide spaces to enhance the viewer’s experience of the artwork. Much of the original ornamentation remains. Diener wanted a simple look. Nothing superfluous, nothing grandiose.

“He understood painting and he was fond of old buildings,” Angela tells me.

Picasso was a friend of the Rosengart family, so the entire ground floor features his works, mostly from the later decades. One moves through the work chronologically. For example, one gallery is primarily dedicated to the ’50s, while the next covers the early ’60s. There are many paintings of Picasso’s various lovers.

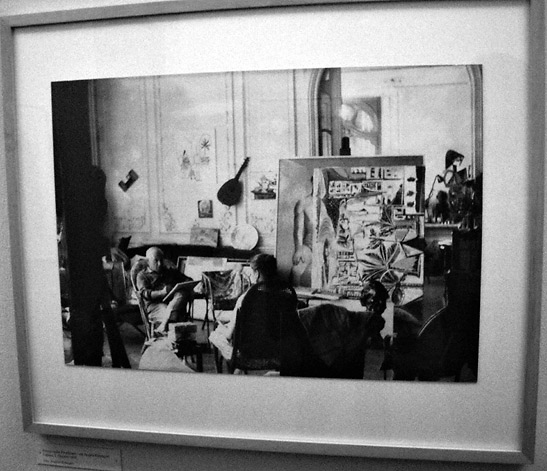

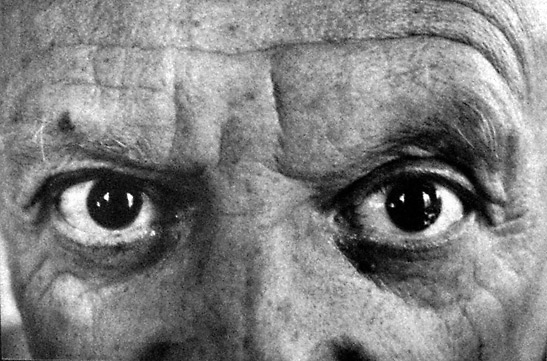

Picasso even famously sketched and painted Angela Rosengart herself. Another floor features David Douglas Duncan’s photographs of Picasso at work in his studio, including a few shots from October, 1963, with Angela sitting in a chair, as Picasso draws her.

“I had to sit there and endure the looks from his eyes,” Angela tells me. “The looks were like arrows.”

As we move through the rooms, I can feel the sheer vitality of Picasso’s output emanating from the walls of Pilatusstrasse 10. It’s like stepping into his very own studio. For example, as we turn a corner, Angela leads me into another space featuring some of Picasso’s etchings from 1968.

“He did something like 347 etchings that year,” she explains. “He would complete one after the other.”

Nothing beats exploring a three-story art collection, guided by the benefactress herself. I’m almost star-struck. It’s hard to speak. Yet Angela is no rock star. During my tour, tourists filter through and ask the inevitable vacuous question: Which painting is your favorite? But Angela says there’s no way to answer. It changes every day. This is also how writers respond when readers pry into which story, or book, or column is the most favorite one, a question no writer can answer, except to say, “That’s like asking which one of your children is the most favorite one.” So I get it.

With the utmost of humility, Angela won’t even refer to the works as a collection. Instead, she repeats over and over that she “simply has beautiful pictures.”

Aside from Picasso, the beautiful pictures include works by Paul Klee, Matisse, Monet, Kandinsky, Leger, Braque, Seurat, Renoir and Cezanne. With even more humility, Angela reiterates that the entire “collection” happened by accident. She and her father never planned to present them as a “collection” of any sort.

“The paintings were acquired over the years and we just didn’t want to part with them,” she admits.

In fact, her father never even planned to be an art dealer in the first place. That was likewise accidental. Initially, Siegfried served as general manager of the Lucerne branch of the Munich-based Thannhauser Gallery before taking over the gallery himself in 1937. After that, he operated the business as sole owner under his own name. His life just unfolded in such a way that he became a world-renowned dealer and agent.

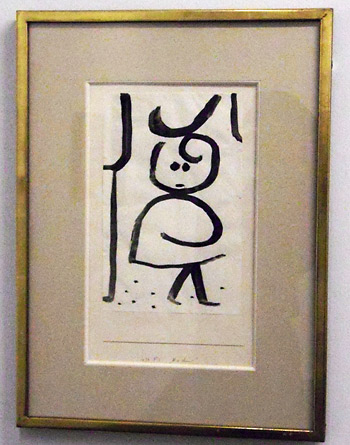

Angela grew up with it all. At age 17, she purchased her first work, a piece from the Paul Klee estate. She paid fifty Swiss Francs, one month’s salary at that time, for a piece titled Little X. The piece now adorns one wall in the museum.

Eventually Angela joined on as co-owner of the business and although the father and daughter made a living buying and selling works of art for decades, they often found themselves in a dilemma. In their hearts, they really didn’t want to get rid of anything. They developed a personal attachment to many of the works.

None of which could have been planned. Growing up, Angela never dreamed Pablo Picasso would eventually draw her likeness five times. He gave her all the drawings, a few of which also hang in the collection.

“I like to say I snuck into immortality through the back door,” she tells me, with a subtle grin.

I get the feeling she’s probably rattled off these lines before, but if I had received my own portraits directly from Picasso, I’d repeat myself a thousand times. I’d shout from the street corner. I’d run down to the bar and tell the story over and over.

Yet Angela doesn’t need to show off. She instead exudes an overflowing sense of gratitude, humility and a Zen-like serenity—all of which is infectious. As we stand there, tourists continue to filter through and pillory her with the same questions she’s been asked for decades. She rolls with it. There is no ego. In fact, it feels no different than a hostess introducing me to her family, the paintings being her kin, of course.

We then move into yet another room. Gracing one wall is the painting, Dancer II, by the Catalan master Joan Miro.

“He was a friend too,” Angela adds.

Finally, we descend into the basement, formerly the vault of the Swiss National Bank, now split into separate rooms dedicated entirely to the Swiss artist Paul Klee. Over 100 of Klee’s watercolors, drawings and paintings hang chronologically, providing tremendous insight into the evolution of his various styles and themes.

In the basement, the walls seem three feet thick. It cost $100,000 to break through one wall in order to divide up the space. The concrete floor is now covered with 100-year-old wood flooring that Diener discovered in an old home. The flooring gives the basement a homey feel.

“It has a new life,” Angela says.

Angela never married or had kids. She tells numerous visitors that the paintings are her children, a line I again sense she’s been forced to repeat many times.

Through Angela, I experience a living connection to some of the twentieth century’s most illustrious artists. If she indeed snuck into immortality through the back door, then I am now one trans-generational Kevin Bacon degree of separation from Picasso, Miro, Paul Klee and Chagall. Only in Lucerne could I say this. No matter what happens, Angela will live forever through this immaculate collection, an inspiration to anyone whose life has unfolded by accident.