By Ed Boitano, Photographs by Deb Roskamp

After my arrival at Heathrow Airport, I was whisked away in one of London’s famous Black Cabs. I was relaxed and feeling carefree, well aware that a London Black Cab driver knew every part of the city like the back of their hand. Unlike U.S. taxi or Uber drivers where the gig is often a part-time one, being a London Black Cab driver is nothing less than a proud full-time endeavor. Four-years of training and person-to-person non online tests is required to be one. By simply naming an address, establishment or even a landmark you will be transported to your place of interest without any form of hesitation. Many of the drivers have achieved such a level of success that they’ve purchased their own expensive Black Cabs, which featured unique modern amenities that seemed almost futuristic to me. The drivers can be chatty, too; interested in who you are and where you’re from, and most importantly serving as an ambassador of London.

London, England. Sept 2023.

It had been five-long years since my last trip to London, and I was interested in seeing how the city has changed. Disengaging the Black Cab by the West End’s St. Martins in the Field, I could see Trafalgar Square – still the de-facto location for swarming crowds to celebrate national events and ceremonies. In its center remained the towering 18 ft. statue of Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson who had knocked out both the French and Spanish war vessels in the Battle of Trafalgar during the Napoleonic Wars. With apologies to Winston Churchill, Nelson remains Great Britain’s national hero with a population still feeding off his glories.

Charles Dickens Museum

It should come to no surprise that Charles Dickens is considered one of the greatest writers in the English language. The London author and social critic was highly regarded as a literary genius during his own lifetime, unlike other artists who had lived in obscurity, only to find an audience long after their passing. Our contemporary vernacular is endowed with words believe to be coined by Dickens, butter-fingers, the creeps, a-buzz, and for many it would not be Christmas without a stage adaptation of his novella, A Christmas Carol.

Dickens’ former three-story Georgian home is where he lived with his wife, Catherine and their eldest three children for two-years. His home is now a museum, which includes bedrooms, study, kitchen dining room, all in period decor. In the two years that Dickens lived in the house, he completed The Pickwick Papers (1836), wrote Oliver Twist (1838) and Nicholas Nickleby (1838–39). Though Dickens’ novels are not considered autobiographical, there are many autobiographical elements in them. Mary, his wife’s 17-year-old sister, had also lived with them, and died in his arms after succumbing to an illness. She inspired many characters in his books, and her death is fictionalized in Little Nell (1837). Dickens was also deeply affected by his experiences working as a young man on the banks of the Thames to support his family, who were in debtors’ prison. This led to his goal of helping London’s poor as a true social and economic crusader, which included trying to counter the contaminated air, particularly in the East End where industrial smoke mixed with London’s infamous fog contributed to countless deaths. Sources indicated that the polluted air also stunted the growth of young children in East End, leaving them weak and malnourished.

National Portrait Gallery

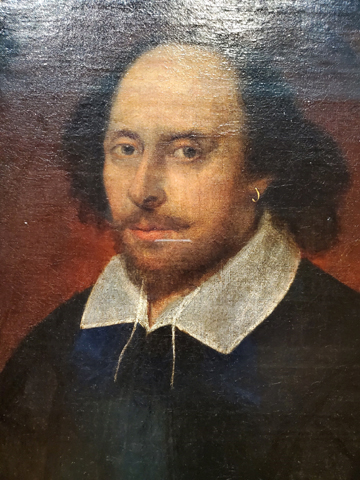

At the National Portrait Gallery, you’ll get the best look of many pre-photographic famous people – though, like today’s photo shopping, you will see them looking far more attractive than they probably really were.

William Shakespeare (1563-1616) painted by John Taylor. This painting of the iconic playwright, actor and poet was the first portraiture acquired by the National Portrait Gallery upon its founding in 1856. It is considered the only known portrait of him painted while he was alive. After Shakespeare’s death, his reputation grew, and artists created portraits and narrative paintings of him, generally based on this earlier image or from their own imagination.

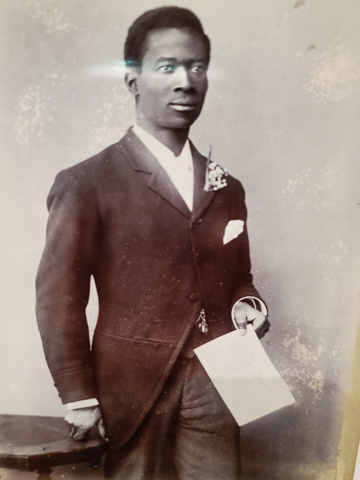

Celestine Edwards (about 1857-1894) painted by William Harry Horlington. Edwards was a Methodist preacher, medical student and Britain’s first black newspaper editor. At age 12, he stowed away on a ship departing Dominica, eventually settling in Britain. In the 1890s he founded the Christian newspaper, Lux, and the anti-racist magazine Fraternity, inspiring younger Black Britons with the widespread movement of solidarity among people of African heritage. His campaigns spearheaded civil rights throughout the world.

The Bronte sisters: Anne, Emily and Charlotte (about 1834) painted by their teenage brother, Branwell. The only surviving group portrait of one of Britain’s greatest literary families, discovered in 1914, folded on top of a cupboard in an Irish farmhouse. The Gallery made the decision not to restore it, retaining its paint loss and fold marks due to its remarkable history. The Bronte Sisters’ best-known novels include Anne’s Agnes Grey, Emily’s Wuthering Heights and Charlotte’s Jane Eyre, all published in 1847 under the masculine pseudonyms, ‘Action Bell,’ ‘Ellis Bell’ and ‘Currer Bell.’ In a sense, their works were intended to address their own experiences in Victorian society at a time when it was not easy to be a woman.

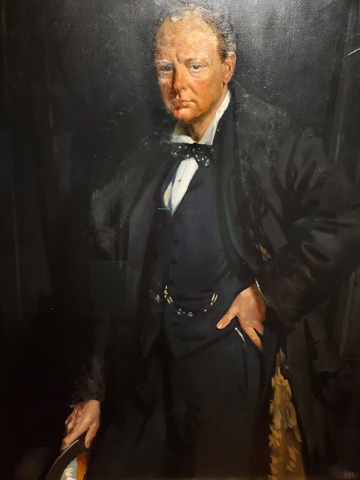

Sir Winston Churchill (1874-1965) painted by Sir William Orpen. The portrait shows an emotionally wounded Churchill after he had resigned as the First Lord of the Admiralty during the First World War, due to orchestrating a disastrous naval campaign in the Dardanelles Straits. By linking Turkey to Europe, he created a second front, which resulted in the deaths of 46,000 thousand soldiers, many of whom consisted of the newly formed ANZAC (Australia New Zealand Army Corp), who had made suicide charges against battle tested Ottoman Turks in Gallipoli. Orpen described Churchill as ‘a man of misery who had lost pretty well everything,’ while Churchill concluded that it was ‘not a picture of a man, but of a man’s soul.’

The Garden Museum

I was surprised to find a such a thing as a museum devoted to gardening. But, after all, this is London; one of the museum capitals of the world, with special thanks, of course, to Greece and Egypt. Nestled on the grounds of the deconsecrated church of St Mary-at-Lambeth, I could see picture-perfect views from its gardens of the British Parliament and Big Ben on the opposite banks of the Thames. My time inside was rewarding, where the museum offered easy access to the working records of leading British garden designers of the 20th and 21st century. I also discovered the narratives of great gardeners through a collection of artifacts and tools from gardening throughout history. In addition, my tour included botanical art, photography, and paintings exploring how and why we garden.

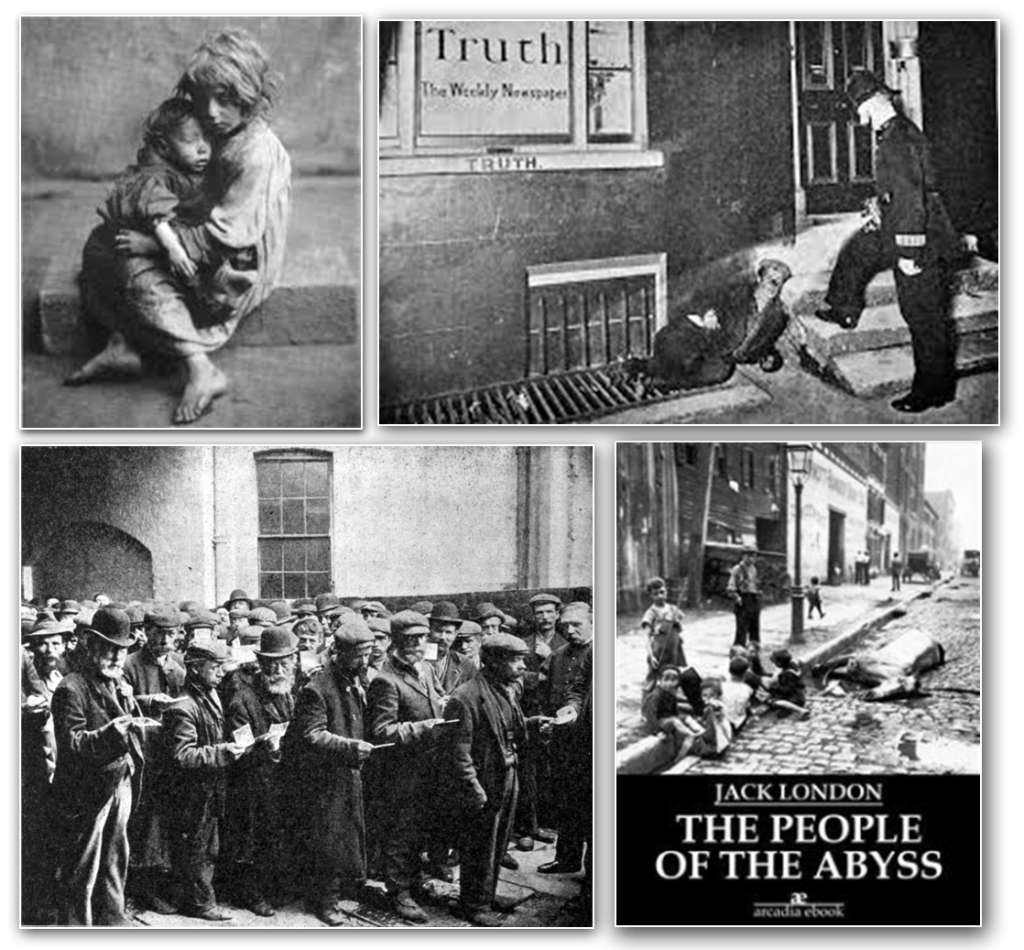

The East End

The East End lies east of the Roman and medieval walls of the Old City of London, north of the River Thames. When U.S. writer Jack London ordered a taxi in 1902 to the deprived Whitechapel district in the East End, the area was so obscure for London’s main populace that he was forced to give the driver instructions on how to find it. In his book, The People of the Abyss, he went undercover, purchasing ragged clothing to wear so that he could live among the destitute in an attempt to understand their daily routine of starvation, homelessness, disease, theft, prostitution and discrimination with no hope for a better tomorrow. The lines of people at charitable foundations were so long and time consuming that many of the weak would fall asleep while standing. Some never made it inside. It was not unusual for a single person to share a cramped one-room apartment with 18 others, making sleeping while standing a requirement. The dire conditions which Jack London experienced were the same as those endured by an estimated 500,000 of the contemporary London poor. In 1902, the life expectancy in the East End was 35-years-old; in London proper, 60-years-of-age.

I was a bit cloudy about the East End, thinking this was simply an area where the Cockneys of London lived. But what does ‘Cockney’ really mean? Research told me that Cockney is an English dialect that has a unique pronunciation, grammar, vocabulary and slang. By 1600, the definition of Cockney meant anyone who could hear the Bow Bells at St. Mary-le-Bow, which are now drowned out by modern city noise. The accent is said to be a remnant of early English London speech, influenced by the traditional Essex dialect. But it also had much to do with the area attracting the rural poor, who had their own unique dialects from other parts of England, which spread whiile working in various trades such as weaving, fishing, shipbuilding, and dock work. Even today, England remains a class-conscious nation, where hearing the dialect of a stranger can tell you all you needed to know about them. With waves upon waves of migrants pouring into the East End from outlying areas, the local citizens found themselves competing for a few casual day labor jobs among numbers that reached the hundreds. This was good for the owners, where competition allowed them to dramatically cut daily wages to obscene lows, making the pennies-for-dollars part-time-jobs hardly worth the effort. Upon exploring the East End’s dark cobblestone streets in the mid 19th century, Karl Marx spoke of knifings, bodies in rags and nine-year-old prostitutes pulling him into doorways as nightly rituals, which confirmed his own idealized economic philosophy.

The East End continued to transition with a new breed of migrants: silk weaving French Huguenot refugees, followed by the Irish of the same mode, which led to fierce competition between the two, cumulating with Spitalfield riots of 1765 and 1769. And then, between 1880 and 1914, the East End’s small Jewish community was transformed by the arrival of 150,000 East European and Russian Jewish refugees, who had faced persecution their entire lives. Together, they all helped to create new jobs and workforce. But, the later closure of docks, cutbacks in railways and loss of industry contributed to a long-term decline, removing many of the traditional sources of semi-skilled jobs, which continued during the Second World War’s Nazi Blitz, which had devastated much of the East End, when bombed for 58 consecutive nights.

Bengalis constituted the final mass migration in the 20th century, where they poured into the district to escape the unimaginable brutality, rape and genocide inflicted on them by Pakistani military in their quest for independence in the East End. The East End of Pakistan, that is. The nine-month-long war finally ended in 1971, and the People’s Republic of Bangladesh was officially finally born, but at the staggering cost of an estimated 3,000,000 civilian deaths.

Bengali musician, Ravi Shankar, and former Beatle George Harrison, whom Shankar had earlier taught to play the sitar, orchestrated two benefit concerts in 1971 at Madison Square Garden in New York City, with the intention to fund relief for refugees from East Pakistan. It soon grew to become an all-star musical event, becoming the first-ever massive benefit of its kind. Perhaps Shankar said it best: In one day, the whole world knew the name of Bangladesh.

As I stood by Algate Pump, considered the entrance to Whitechapel, I saw tenement homes mixed with modern buildings, due to fires, bombings and slum clearances. Before me was the Anglican Spitalfields Christ Church, built between 1714 and 1729, courtesy of Queen Elizabeth I, To bring God to the Godless. Steps away was the old and new of historic Spitalfields Market, where huge crowds still browse the different stalls for clothes, food and antiques; the same with Petticoat Lane’s silk weaving markets. Photographer Deb Roskamp and I walked along with life-long London friend, Trish, who added her own personal narrative, explaining that she had once purchased garments at Petticoat Lane Market. The following week we would explore Hadrian’s Wall and the Lake District in England’s North together.

Trish pointed out Toynbee Hall, the birthplace of the international settlement movement, which attracted progressive-minded young men and women to settle among the underprivileged and join programs which would help their lives. And, the Whitechapel Art Gallery, founded in 1901, showcased an array of different art for the people of the East End, with the intention of nourishing their souls.

Later, my own stomach would be nourished at Spitalfields Market, but for now I was happy to enjoy the colorful street art and murals. I noticed one of iconic Argentine futballer, Diego Maradona – the man with The hand of God. The comment stems from Maradona’s response after his controversial ‘handling’ of a goal during the Argentina v England quarter finals match of the 1986 FIFA World Cup, which Argentina went on to win. Later, he said scoring the goal was a symbolic revenge for the United Kingdom’s victory over Argentina in the Falkland’s War four years earlier. What was controversial for me was why is there a mural of him in England, the home of the English team he helped to beat. Was there still a deep seated resentiment of the London populace who had once turned their backs on the people of the East End.

On the far end of district rests the East London Mosque and London Muslim Centre, which offer traditional Sunni Islamic Calls to Prayer, as well as important things to know when arriving from a new or Muslim culture, i.e., educational courses, counseling, advice services for birth, marriage and death. Just around the corner is Brick Lane, known as London’s curry mile, thanks to the numerous Indian, Pakastani and Bengalis restaurants that line the street.

The air was fresh and clean, no longer polluted by life altering toxic waste and chemicals. Overcrowding is also no longer a widespread problem and tourism is an important component of its infrastructure; in particular with many tours devoted to the 1888 Whitechapel Murders attributed to Jack the Ripper. The East End continues to change to the positive, a positive which helps redefine what was once considered one the most heartless places of destitution in the world.

Special thanks to Londoner and life-long friend, Trish Raffeto, who held our hands and pointed out the significance of special sites that my photographer, Deb Roskamp and I might not have even noticed as we explored the London of today with a glimpse at its past.

Further reading:

- Condition of the Working Class in England (1845) by Friedrich Engels.

- Liza of Lambeth (1897) by W. Somerset Maugham.

- The People of the Abyss (1903) by Jack London.

Stay tuned for Part II, which will include The Globe Theatre, West End plays, Churchill War Rooms, Temple London, Somerset House, London Pub Grub and Tea.

Rick

October 26, 2023 at 1:07 pm

It’s interesting to see what people wear — below some of their formal attire, they have their sneakers. I also miss the pigeons. Like, where are the pigeons in Trafalgar Square? For me, that was what struck me the most — people and pigeons sharing that space.

Marco

October 26, 2023 at 1:08 pm

I never realized there was such a thing as the East Side of London. Good historical info. Well done!

Tony Chisholm

October 27, 2023 at 4:52 am

Great narrative Ed. Your descriptions are interesting and full of insight. Always enjoy your writing. Thanks for giving us an inside into today’s London. Great pictures as well, Deb.