Director: Volker Schlöndorff

Director: Volker Schlöndorff

Based on the novel by Robert Musil

Writers: Herbert Asmodi (Adaptation), Volker Schlöndorff (Screenplay)

Cinematography: Franz Rath

Cast: Mathieu Carrière, Marian Seidowsky, Lotte Ledl

Young Törless

By Walt Mundkowsky

Volker Schlöndorff’s Young Törless, which shared the FIPRESCI (International Critics) Prize at the 1966 Cannes Film Festival with Resnais’ La guerre est finie, has finally arrived here, and it emerges as a strange, hypnotic work with deep implications. This is Schlöndorff’s first film, but he has worked as assistant to Louis Malle (on Zazie, Private Life, The Fire Within and Viva Maria), Resnais (on Marienbad), Jean-Pierre Melville (on Le doulos, a crime thriller with Belmondo), and Antonioni; he has learned well from all of them.

We begin at a boarding school in pre-W.W. I Germany. Törless (Mathieu Carrière) is an aloof, sensitive young aristocrat. (“I wish my son were more like you,” his father tells one of the other boys. “I don’t know what to make of him.”) The sadistic urges of the students are apparent from the start — a boy slowly killing a fly with his fountain pen during class. Some of the boys break up the monotony of their routine with visits to Bozena (Barbara Steele), a prostitute with a child. She sees the school as a miniature society, embodying all the evil of the world outside. (“Everyone was so nice to me — until they saw I was pregnant.” She tells Törless and his friend, “You’re exactly like they are: hypocrites — and liars.”)

Törless is suddenly involved in a sickening episode. Basini (Marian Seidowsky) owes Reiting (Alfred Dietz) some money; he cannot pay it, so he steals from Beineberg (Bernd Tischer), a friend of Törless. Reiting goes to Beineberg, but they do not report Basini; instead, he becomes their slave and guinea pig. At first Törless is just as enthusiastic as the others (“Basini is a thief and must be punished”), but he soon realizes how vicious they are. “It’s not the punishment that interests me,” Beineberg admits. “I’d like to — let us say, terrify him.” And later: “I want to destroy these wasteful sentiments of mine.” Basini is beaten and forced to repeat, “I am a thief. I’m a dog, a thieving dog, your thieving dog.” Törless cannot comprehend Basini’s refusal to fight back. (“Didn’t you feel something awful happening inside you? When they spat on you, when they had you lick the floor —”)

The bouts of torture assume the guise of experiments. “There must be something that is more powerful than logic,” Beineberg intones. “I call that the ‘soul.’” He puts Basini into a trance and tries to make his body float. Törless can no longer watch impassively. (“I was looking for something, but I see only brutality. There isn’t a good world and an evil world. They’re the same one. That’s the whole story.”)

Basini does not go to the school authorities, even after Törless warns him that Beineberg and Reiting plan to turn him over to the class. Törless runs away after the student body vents its wrath on the hapless Basini. After seeing Bozena, he goes back to school as the incident is being investigated; the administrators interview him. In this beautifully photographed and edited sequence the film’s intent becomes clear. Asked why he went along with Basini’s torture, he replies, “I don’t know — at first it was all so unbelievable. Yes, it seemed to me that reason and logic weren’t enough, that man isn’t made for either good or evil. Then everything is possible — even the most horrible atrocities … what seems so inconceivable just happens.”

It is decided that Törless is “a strange boy.” He does not return to the school. The film ends on neatly modulated irony. Törless is riding away from the school with his mother in the family carriage. But the school is a kind of metaphor for society — particularly the Nazi society to come. As William Golding wrote of the ending in his Lord of the Flies, “The officer, having interrupted a manhunt, prepares to take the children off the island in a cruiser which will presently be hunting its enemy in the same implacable way. And who will rescue the adult and his cruiser?”

Mathieu Carrière has the right elegance and bearing for Törless. Only 16 when it was shot, his delivery during the interrogation scene impresses — assured but not arrogant, passionate but not histrionic, both amazed and understanding. This young performer conveys the essence of nobility. He does not act superior, he is superior. Bernd Tischer and Alfred Dietz are gripping as two very different sadists. Only Marian Seidowsky (as Basini) fails to convince. The part isn’t easy, but he makes no lasting dent. The smaller roles are capably handled.

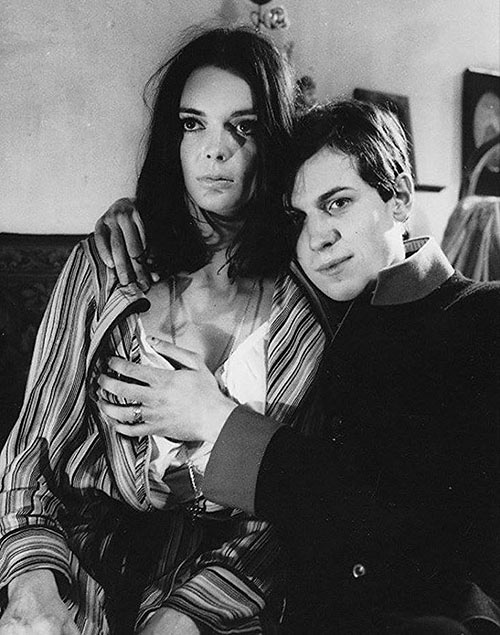

Barbara Steele finds so much in the character of Bozena that she affects us even when not onscreen. Steele is much too beautiful for the part but she succeeds anyway, giving us Bozena’s grit, cynicism, humor, openness, fragility — all of it. After her turn as the neurotic intellectual in Fellini’s 8½ and this, it is obvious that she can be much more than the horror icon (Mario Bava’s Black Sunday, etc.).

Barbara Steele finds so much in the character of Bozena that she affects us even when not onscreen. Steele is much too beautiful for the part but she succeeds anyway, giving us Bozena’s grit, cynicism, humor, openness, fragility — all of it. After her turn as the neurotic intellectual in Fellini’s 8½ and this, it is obvious that she can be much more than the horror icon (Mario Bava’s Black Sunday, etc.).

The direction is a model of economy; Schlöndorff also wrote the screenplay. His years as an assistant director lend the film an unforced technical finesse. Franz Rath’s austere black-and-white camerawork captures the harshness of setting and theme. Influences Schlöndorff has assimilated make this movie stunning: the opening slow pan reminding one of Antonioni; tracking camera movements from Resnais; Malle’s feeling for close-ups; classical positioning of actors à la Melville and Resnais. But Schlöndorff has welded these elements into a highly individual style. Hans Werner Henze’s music is enormously helpful, imparting a density and force to the proceedings. It’s tricky as well — modern 12-tone pages done on Renaissance instruments. Schlöndorff was fortunate to engage him, as film scores (also Resnais’ masterpiece Muriel) are but a tiny corner of Henze’s output.

The outcry against detachment is well-populated, but Young Törless has a brainy eloquence that stands out. This barbed adaptation of a near-classic (Robert Musil’s 1906 novel) leaves Schlöndorff’s future path open, but the unity of style and the skill with a mostly young cast can make one hopeful.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.