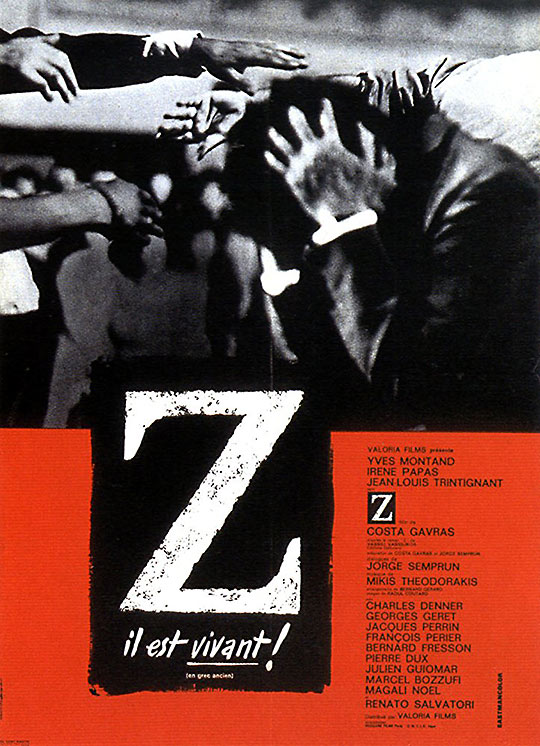

Director: Costa-Gavras

Director: Costa-Gavras

Writers: Vasilis Vasilikos (novel), Jorge Semprún (dialogue)

Cinematography: Raoul Coutard

Music: Mikis Theodorakis

Orchestrator: Bernard Gérard

Sound editing: Michèle Boëhm

Stars: Yves Montand, Irene Papas, Jean-Louis Trintignant, François Périer, Jacques Perrin, Charles Denner, Bernard Fresson, Marcel Bozzuffi, Renato Salvatori

Z – A Look Back

By Walt Mundkowsky

Costa-Gavras’ Z predisposes one to admire it, as the first film to indict the brutal military regime in Greece; in fact, the music by the long-imprisoned Mikis Theodorakis had to be smuggled out of the country. From the bitter opening title card (“Any similarity to actual events, or persons living or dead is not coincidental. It is intentional”) our sympathies are engaged. And Z is remarkably well made; not once in its 127 minutes does it relax its grip. As a political statement, however, the movie is suspect, and its style calls into question the use of melodrama for political ends.

On May 22, 1963, Gregorios Lambrakis, a professor of medicine at the University of Athens and deputy of the liberal EDA (United Democratic Left) party, went to Salonika to address a Friends of Peace rally. Leaving the meeting, he was run down by a pickup truck and died several days later. Thanks to a young investigating magistrate with extraordinary integrity and a passion for truth, the “accident” was unmasked as an assassination plotted by high-ranking officers in the gendarmerie and carried out by an organization of the extreme Right. The resulting scandal toppled the ineffectual right-center Karamanlis government. Vassilis Vassilikos, an important Greek novelist and a native Salonikan, wrote a semi-documentary novel around the Lambrakis affair; he titled it Z, symbol of the Lambrakis supporters, for the Greek verb zei — “he lives.” Z was banned shortly after the military takeover and Vassilikos fled to Paris. This is the film of his book.

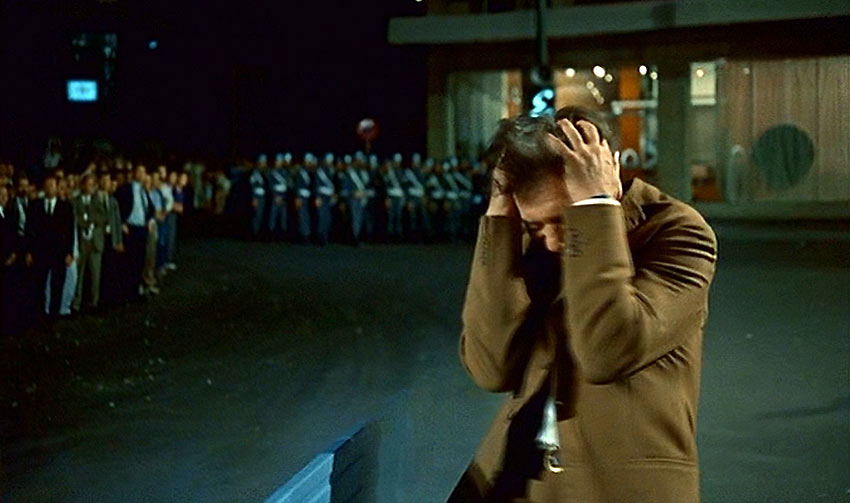

Z seems not so much shot as snared: The camera is frequently on the move, hurrying after the characters; no recent movie has such a pronounced sense of forward motion. Lately, in Chabrol’s Les biches and much Godard, or in Easy Rider and Zabriskie Point, the traveling camera has seemed like so much doodling. Costa-Gavras satisfies Roy Armes’ view of Resnais’ tracking shots: “The camera is the eye of an investigator moving forward to see for himself, at first hand — the director sizing up his subject.” Raoul Coutard’s fluid Eastmancolor camerawork here is a cohesive mix of rough, slightly newsreel-like exteriors and highly composed and lit interiors. Dozens of stunning images result — the shimmering telephoto of Z’s (played by Yves Montand) plane landing, the zoom lens stabbing down an aisle to focus on the X-rays of Z’s skull fracture, the angled long shot of a virtually deserted hospital ward. Or the photographer’s entrance into the film, the camera drawing back from a screen-filling close-up of his 35 mm. Canon’s lens. Pretty pictures edited with a ruthless hand.

Sound editor Michèle Boëhm has assembled an exciting, urgent soundtrack. The hard-driving, heavily percussive Theodorakis score greatly assists the headlong pace. (One passage, when Vago comes out of the newspaper office and rips off his “disguise,” could have employed a buzzsaw.) The music would be good in any case; considering that the composer was unable to see any footage, compliments to musical arranger Bernard Gérard are in order.

At the center of the swirling action, calm as the eye of a hurricane, is the Investigator. The dedication to justice in the face of bribes and threats of all kinds does not become a self-righteous crusade, as it does in a Hollywood film; rather, it is lonely, frustrating and demanding. Jean-Louis Trintignant’s crisp, exacting vocal delivery captures the man’s love of precision. Préciser (to clarify) is a French verb, after all. He cuts off a flimsy, meandering explanation with an impatient “Je connais, je connais” (I know, I know) and greets an uneasy admission with an “Ah!” of mock surprise. A witness begins, “The day of the assassination —” “The incidents,” the Investigator interrupts her. “Say ‘the incidents.’” Later he corrects another witness, adding, “Assassination has not been proved.” When he finally uses the word assassinat himself, it has the force of a fist.

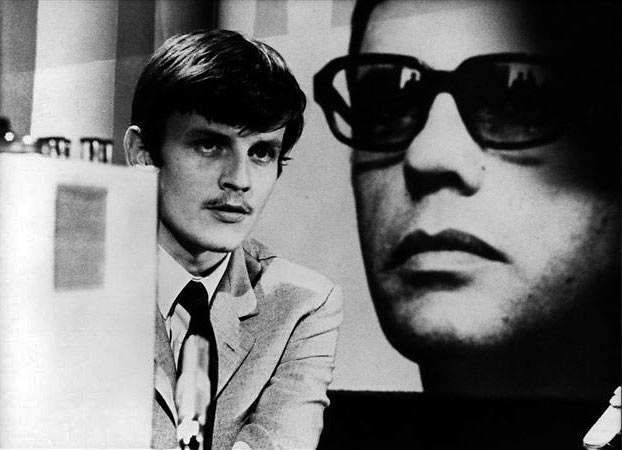

The cracking gait Z sets has its drawbacks: When an intricate plot is related with speed and efficiency, characterization is the first casualty. The sole complex character is a callous, mercenary journalist played by a superb Jacques Perrin. He is capable of astonishing charm, courage, determination, invention; capable of everything short of caring. A bleeding peace demonstrator is carried past him; he nods to his associate, “Sell to the Daily Worker” — supplying the headline — “Victims of Fascism.” He locates the assailant of another EDA deputy. “You must publish it in our paper,” the deputy tells him; but the journalist is going to put it “in a big-circulation daily. It’ll be read, and they pay.” “In an opposition paper,” he continues, “it’s nothing. It’s just ‘politics.’ But in mine, it’s news — sensational news!” He has equal disregard for both sides: His rapid-fire questions literally back Z’s confused, exhausted widow against the wall — all she can do is plead weakly, “Laissez-moi … laissez-moi” (Leave me!); similarly, the tearful confession of a thug is punctuated by a clicking camera shutter. Even Perrin’s face seems to change. Here it is all sharp planes; as the love-struck blond sailor in The Young Girls of Rochefort his features looked soft and adolescent. But this part, wonderfully realized though it is, falls outside the film’s main concern; as the Investigator says, “His motives are anything but political.”

I think Costa-Gavras realized how flat most of the characters remain. He has tried to give Montand’s Z a little depth by cutting in very brief flashbacks. Mostly they are on the Hiroshima, mon amour pattern (Manuel, a lawyer and friend of Z, attempts to console the widow by stroking her cheek — cut to Z making the same gesture), and Costa-Gavras will not make us forget Resnais; their A Man and a Woman tone (Z’s wife snuggling up to him as they drive through a rainstorm, Z playing with his children) does not help matters much — an effort to lend Z some dimension without cluttering it with psychology or deflecting its single-minded drive.

I think Costa-Gavras realized how flat most of the characters remain. He has tried to give Montand’s Z a little depth by cutting in very brief flashbacks. Mostly they are on the Hiroshima, mon amour pattern (Manuel, a lawyer and friend of Z, attempts to console the widow by stroking her cheek — cut to Z making the same gesture), and Costa-Gavras will not make us forget Resnais; their A Man and a Woman tone (Z’s wife snuggling up to him as they drive through a rainstorm, Z playing with his children) does not help matters much — an effort to lend Z some dimension without cluttering it with psychology or deflecting its single-minded drive.

The dialogue by novelist (Le grand voyage) and screenwriter (Resnais’ La guerre est finie) Jorge Semprún is fine, but the actors do more for the lines than the lines do for them. François Périer’s oily, vacillating public prosecutor is so convincing one expects him to leave a trail as he glides across the floor. Renato Salvatori creates a chilling, funny brute out of the mere fact that Yago likes to hit people over the head with a club. Marcel Bozzufi (Vago), his homosexual partner in crime, is even better; his theatrical performance is a useful counterpoint to the film’s quasi-documentary approach. In much the same way, Charles Denner’s Manuel contrasts with the stoical EDA officials. This intense actor’s voice is the razor’s edge in operation. Costa-Gavras felt he needed Irene Papas’ presence in the cast; alas, that presence is all he asked of her. Few grasp more subtleties in bombast than Pierre Dux; his General is an assured, carefully judged turn. The ensemble is so overqualified that Magali Noël can bring her usual fire to the right-wing sister of a witness who simply wants to tell the truth (he’s Georges Géret, the pimp friend in Visconti’s film of The Stranger). And Clotilde Joano’s long, pale face and beseeching eyes fit the concerned wife of an EDA man. The English subtitles are never more than adequate, but the film couldn’t exist without the voices of these actors.

As the old Scot says, I hae me doots. One way to examine Z’s shortcomings is through Françoise Bonnot’s editing. It is brilliant in every sense: Action scenes that are staples of the secret-agent movie — the struggle in the back of a careening vehicle, the man on foot desperate to avoid being run over — are so joltingly cut it seems tiresome to complain. While Z is doing his speech, shots match his points expertly: Over dry statistics (“A strategic bomber costs as much as seven schools”) his fellow deputy is savagely beaten; “Why is peace so intolerable to them?” — the General’s jeep drives up to the crowd. But “brilliant” also means dazzling, narrowly applied, superficial. Z is a political thriller that lacks “the thrill of comprehension” (Brecht). If you know anything about recent events in Greece, your understanding will not be enlarged. Vassilikos attempts (not entirely successfully) an analysis, but not Costa-Gavras — he is unwilling to take the risk of boring us.

The potent acting and technical authority give Z the illusion of substance. It is hard to reproach any film which opposes the military rulers of present-day Greece, but one wishes Z were better. It tells us less than we want to know; despite many strong virtues, it is finally not quite enough.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.