Director: Arthur Hiller

Director: Arthur Hiller

Writer: Paddy Chayefsky

Cinematography: Victor J. Kemper

Stars: George C. Scott, Diana Rigg, Barnard Hughes, Richard Dysart

The Hospital

By Walt Mundkowsky

In The Hospital the screenwriter – director team of Paddy Chayefsky and Arthur Hiller does for modern medicine what it did for war heroism in The Americanization of Emily: They set out to score cheap, quasi-satiric points off a target so large and helpless that one is almost inclined to take pity on it, and fail even on their own cowardly terms. Chayefsky and Hiller came from the TV of the 1950s; the writer is perhaps the best known of the Philco – Goodyear Playhouse set, that stable of playwrights who produced the Golden Age of Midcult. An occasional obscenity aside, The Hospital looks horrifyingly like those dramas (another of the group, Reginald Rose, carried the approach to new depths on The Defenders). It begins with an air of truth-telling about a complex, interesting subject. In fact, the concern is not at all for truth per se, but for making truth fit into a container that will not discomfit anyone. The subject is not allowed to carry Chayefsky where it will; he pours in as much truth as the compromises and fakeries will support, and no more. This is a low-grade conjuring act; in the end the topic vanishes before your eyes.

The Hospital opens with a prologue that promises a loose, funny view of medical practice, but it is in full retreat most of the time. This annoys, for Chayefsky has a premise that might have made a slashing film. The deaths on the hospital staff pile up, and the hospital machinery is doing the killing. The staff becoming, inadvertently or otherwise, patients in their own hospital and being killed off by it — follow that idea with nasty, unsparing logic (I imagine Elio Petri directing it) and what a movie you would have! Chayefsky, though, is determined to send everyone home in a cheery frame of mind, so the various snafus we have been laughing at are revealed as the work of a spectacularly gifted lunatic. The final cop-out has been noted everywhere; by then nothing is left to subvert.

Cleverness is not a quality associated with Chayefsky; huge wads of exposition are put in the characters’ mouths. Dr. Bock, the film’s protagonist, is described as “a man exhausted, emotionally drained, riddled with guilt”; he unfolds his life story in a series of long set-piece speeches. None of them has much dramatic shape, and several are delivered in preposterous circumstances (to a woman he has just met). The speeches are so inept that they can be identified by their own tag lines — the “What the hell is wrong with being impotent?” number, the “Someone’s got to be responsible” one, and so on. But even those are preferable to the wheezing pseudo-poetry: “I’m offering you green silence and solitude — a natural order of things. Most of all, I’m offering me.” More offensive yet is the handling of the demonstrations, which show Chayefsky as the liberal out on a shopping tour who isn’t about to pass up anything on the Contemporary shelves.

Cleverness is not a quality associated with Chayefsky; huge wads of exposition are put in the characters’ mouths. Dr. Bock, the film’s protagonist, is described as “a man exhausted, emotionally drained, riddled with guilt”; he unfolds his life story in a series of long set-piece speeches. None of them has much dramatic shape, and several are delivered in preposterous circumstances (to a woman he has just met). The speeches are so inept that they can be identified by their own tag lines — the “What the hell is wrong with being impotent?” number, the “Someone’s got to be responsible” one, and so on. But even those are preferable to the wheezing pseudo-poetry: “I’m offering you green silence and solitude — a natural order of things. Most of all, I’m offering me.” More offensive yet is the handling of the demonstrations, which show Chayefsky as the liberal out on a shopping tour who isn’t about to pass up anything on the Contemporary shelves.

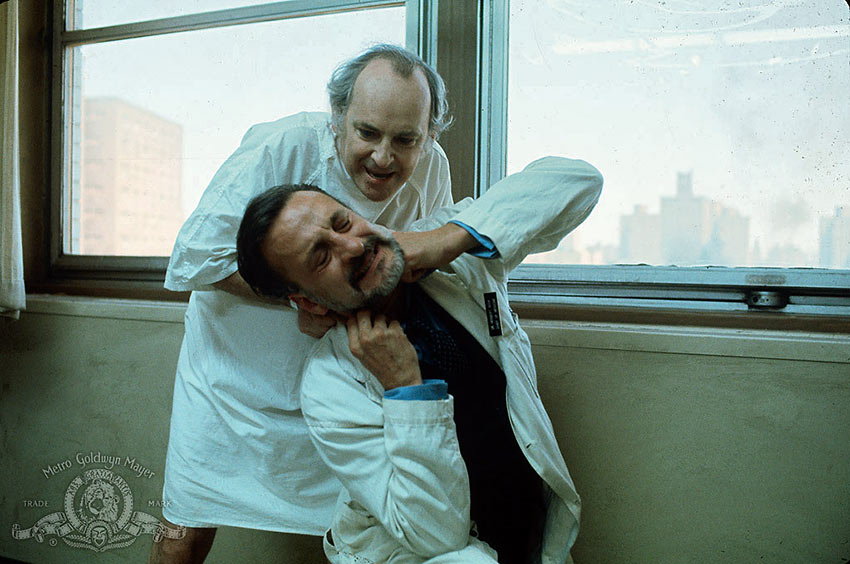

Hiller has directed with M*A*S*H clearly in mind. The brief scenes, impatient editing, contrapuntal use of visual planes (Diana Rigg is glimpsed on the periphery of several scenes before she is introduced to us), overlapping conversations. Hiller has gone to some trouble to reproduce Robert Altman’s surface, but he has neglected the key feature Altman brought to M*A*S*H — a framework within which even the most outrageous behavior could be understood. In The Hospital the tone is frequently off, and the mounting insanity in the picture spills over into Hiller’s grip on the material. The film is visually nondescript, and does not exploit the possibilities of the hospital setting nearly as well as, say, Bullitt did in much less time.

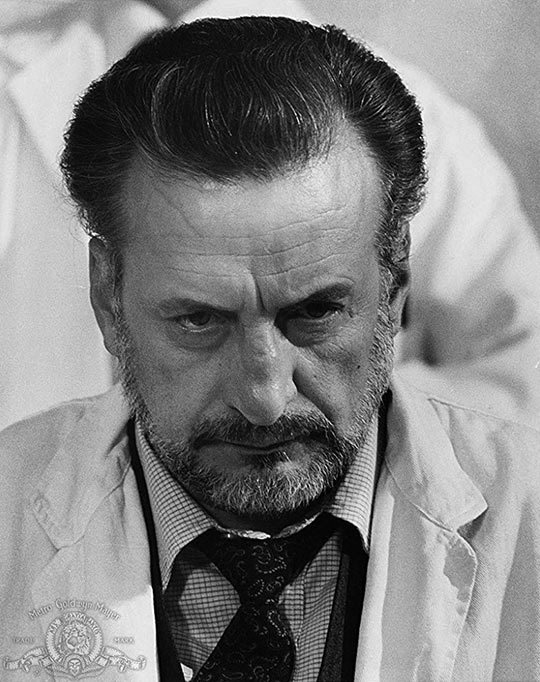

Still, much of the movie is entertaining, thanks to George C. Scott’s performance as Bock. What he does with the maladroit language is sheer alchemy, transforming “I mean, my God, where do you train your nurses, Mrs. Christie — Dachau??” (and countless others) into a rapier thrust of wit. The film is set up so that Scott can walk away with it — throughout he seems to be in on a joke nobody else knows — but the focus gravitates to him naturally. Scott’s accomplishment is to make tripe stunning, a triumph of technique over matter; he has done this part before, with subtler gradations, in Richard Lester’s Petulia. But as usual, he is exciting and vivid. Diana Rigg is stuck with Chayefsky’s idea of an ex-S.D.S. hippie. She seems lost much of the time, but what expression would be suitable for “I want you to come with us because I love you and want children” or “I can retain my sanity only in a simple society.” Smaller roles benefit from New York’s deep pool of stage and TV talent, with Richard A. Dysart outstanding as a hustler surgeon Bock calls “that BARBER!”

Still, much of the movie is entertaining, thanks to George C. Scott’s performance as Bock. What he does with the maladroit language is sheer alchemy, transforming “I mean, my God, where do you train your nurses, Mrs. Christie — Dachau??” (and countless others) into a rapier thrust of wit. The film is set up so that Scott can walk away with it — throughout he seems to be in on a joke nobody else knows — but the focus gravitates to him naturally. Scott’s accomplishment is to make tripe stunning, a triumph of technique over matter; he has done this part before, with subtler gradations, in Richard Lester’s Petulia. But as usual, he is exciting and vivid. Diana Rigg is stuck with Chayefsky’s idea of an ex-S.D.S. hippie. She seems lost much of the time, but what expression would be suitable for “I want you to come with us because I love you and want children” or “I can retain my sanity only in a simple society.” Smaller roles benefit from New York’s deep pool of stage and TV talent, with Richard A. Dysart outstanding as a hustler surgeon Bock calls “that BARBER!”

The Hospital reached Blu-ray on December 19, from Twilight Time.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.