Fall Foliage Trip Planning

Written by Kim Knox Beckius

The annual display of colorful fall foliage clogs scenic byways this time of year as onlookers travel for “leaf peeping” getaways. As the trees put on a memorable show for us, behind the scenes, it’s due to the slowing of chlorophyll production. That’s what’s going on, you see: an un-greening of leaves that unveils the true colors that have been masked throughout the summer. As underlying pigments pop, lighting up the landscape, mountainsides and roadsides truly do warrant gawking.

And yet, it’s not just the season’s radiance that spurs travelers to road trip or even to fly great distances for a fall foliage getaway. Nor is it pumpkin spice everything! It’s the crisp cleanness in the air that makes this one of the healthiest times of year for hiking, biking, and other outdoor pursuits; the sounds, scents, and tastes of this season of harvest; and the childhood memories fall invokes. When you visit a destination known for its fall foliage, you’re also revisiting the part of yourself that knows days must be seized before cold weather snatches the fun away.

Here’s our complete guide to planning the perfect autumn trip, to spot gorgeous colors across the country, and enjoy the season and crisp temperatures it offers before winter sets in.

Top Destinations for Fall Foliage

So, where will you go for a colorful escape? The U.S. has some truly standout fall foliage spots.

New England: No region of the country is more legendary for its fall colors than New England, and with six history-loaded states in compact proximity, the options for sightseeing and leaf-spotting are nearly limitless. Dense stands of deciduous trees that turn bright all at the same time make New England’s hillsides fiery backdrops for days spent picking pumpkins and nibbling on cider doughnuts. Around every corner, there’s something pretty to photograph, whether it’s a white church, a covered bridge, or a gazeboed town green straight out of “Gilmore Girls.”

New York State: New England’s neighbor is no slouch when it comes to fall colors. Once you’re out of NYC, it’s tough to choose where to head for fall splendor: the Catskill Mountains or the Adirondacks, the Hudson River Valley or the Genesee River Valley, or the Finger Lakes region, where you can leaf-peep and sip wine. Travelers who spend time on Lake Champlain’s New York and Vermont sides really maximize their opportunities to see awe-inspiring scenery.

Upper Midwest: It’s not surprising that the Upper Midwest was attractive to westbound settlers from New England in the first half of the 19th century. The regions share climatic similarities, and fall is the most wondrous of four distinct seasons. Northern Michiganders, in particular, will tell you their foliage rivals anything New England has to offer. Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, with its nearly 9 million acres of forested land, wows leaf peepers with its vibrant leaves and water features.

Blue Ridge Parkway: If the idea of one magnificent fall foliage drive excites you, you can’t beat the 469-mile Blue Ridge Parkway, which runs from Shenandoah National Park in Virginia to Great Smoky Mountains National Park in North Carolina. Plan on spending two days or more admiring the autumnal scenery from every angle as you follow this dramatic road, which snakes along the spine of the Blue Ridge: part of the Appalachian chain.

Colorado: Known for its stands of aspen trees, with their white-powder trunks and leaves that turn a shocking shade of yellow in the fall, Colorado promises leaf lovers five weeks of color starting in the north and progressing south as October days shorten. In a state known for dramatic mountains, crystal-clear lakes, and more hiking trails than you could ever explore, the arrival of fall adds an overlay of vibrancy that is simply stunning.

When To Go

Timing is everything if you want to see leaves at their peak, so choose the dates you will travel thoughtfully. Keep in mind, though, that it is impossible to predict the exact progression of the season. As a rule, fall colors arrive earliest in higher elevations and the farther north you travel. In New England, for example, Connecticut and Rhode Island can still be green while the northern parts of Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont are already dazzling road-trippers. The earliest you’ll see strong color anywhere in the U.S. is mid- to late September. The latest is the first week or two of November.

Best Ways to See Foliage

Driving trips offer the most flexibility when it comes to navigating the autumn landscape. You can drive up mountains, steer along country roads, and check foliage reports to see where the scenery is at its best. A motorcoach trip can also be a good option if you prefer to sit back and admire the view. Don’t overlook more unusual ways to leaf peep, such as aboard a cruise ship, historic sailing vessel, or tour boat. The contrast of blue water and orange, red, and yellow trees makes for striking photographs. For active travelers, this is a spectacular time of year for paddling, biking, and hiking trips. Fall’s also a perfect time to fly high above the leaves on a zipline, aboard a ski-area skyride, or in a helicopter or hot air balloon.

What to Bring

Fall weather can be fickle, so pack clothing you can layer: T-shirts, long-sleeved shirts, sweaters or fleece pullovers, a vest, a jacket. The later in the season you travel, the more likely you are to need a warmer outer layer and gloves. Keep in mind that while days can be sunny and warm, it’s cold nighttime temperatures that rev up the fall color show.

You’ll also want to bring along:

- An umbrella

- Comfortable footwear for walking

- Extra socks

- Sunglasses

- The best camera you own

Helpful Tips for Fall Foliage Trips

- Invest in a printed road map of your destination, not only because GPS service isn’t always reliable in remote locations but because it will take you back to a time when finding your own way was half the fun.

- Don’t overestimate the number of miles you can cover in a day. With roadside attractions and fall vistas beckoning you to pull over — plus added traffic along popular routes — you might not make the time you expected.

- Have snacks and drinks with you at all times. The best foliage routes aren’t populated with fast-food joints.

- Make hotel reservations far in advance for the busiest travel weekends in popular foliage spots, such as Columbus Day weekend in New England.

- Make your trip about the myriad of fall sights and experiences — not just viewing leaves — and you won’t be disappointed if Mother Nature doesn’t quite cooperate.

5 Things Science Says Will Make You Happier

Research-backed habits that will improve your outlook and positive attitude

By Nataly Kogan

Medically reviewed by Daniel B. Block, MD

It’s easy to assume that things like money and a luxurious lifestyle lead to happiness, but research shows that it’s the more simple experiences — like practicing gratitude or spending time with friends — that promote a sunny outlook.

Whether you need to shift from negative thoughts or want to continue a streak of positivity, here are five ways to boost happiness every day.

Rumination: Why Do People Obsess Over Things?

Practice Daily Gratitude

Expressing gratitude has been shown to do more than improve your mood. People who write down a few positive things about their day are healthier, more energetic, less stressed and anxious, and get better sleep.

The key is to make this a regular habit and to do it with intention. Think about creating a small gratitude ritual. For example, every morning when you have your coffee, try thinking of three things that you appreciate about the previous day. Or make it a habit to jot down three positive things about your day before you go to bed at night. Your three things can be seemingly small (a beautiful flower you saw during a walk) or big (the fact that you’re healthy). In fact, science shows that it’s the small everyday experiences that make us happier, compared to big life events.

3 Simple Ways to Cultivate Gratitude

Surround Yourself With Positive People

Happiness is contagious. A landmark 2008 study found that living within a mile of a happy person boosts your own happiness by 25%. If you’re feeling down, reach out to a friend who generally has a more positive attitude. Your brains have mirror neurons that will literally mimic what another person is expressing; so when you need a bit of positive infusion, connect with those who share it.

Practice Regular Acts of Kindness

Research has shown that spending money on others makes us happier than spending money on ourselves and doing small acts of kindness increases life satisfaction. Even the smallest nice gesture can make someone’s day. Here are a few easy ways to show kindness:

- Hold the door open for someone behind you.

- Say thank you and mean it when you pick up your next cup of coffee.

- Donate clothes to a local shelter.

- Help an elderly neighbor with yard work.

- Bake a dessert to share with your coworkers.

Spend More Time With Family and Friends

Friendships can be one of the keys to longevity. In fact, one study found that low social interaction — and in turn, loneliness — can be as bad for you as smoking 15 cigarettes a day and is twice as bad for your health as obesity.

Even if you’re busy you can find ways to connect with people you care about.

Use your lunch break as an opportunity to call a friend or, if possible, take a walk together. If you’re busy during the week, consider inviting your friend to do some errands together on the weekend.

Invest in Experiences, Not Objects

Research shows people report feeling happier when they spend their money on experiences rather than objects. We remember experiences for a longer period of time and our brains can re-live them, making our positive emotions last longer. So instead of that new pair of jeans consider trying a new yoga class or inviting a friend to the movies with you.

A Word From Verywell

While these ways to increase happiness may come easily to some people, if you’re coping with depression, chronic stress, or other psychological illnesses, it can be difficult to see the bright side. Remember that every day is different and that these are practices to work on daily. If you continue to have difficulty coping, consider talking to a friend or family member for support, or contact your doctor for advice on next steps.

The Future of History in the Pandemic Age

By Michael Creswell

Historians need to consider and prepare for changes to the profession that will follow the COVID-19 pandemic.

Attempting to predict the future is always perilous, and events frequently humble those who dare to try. Making predictions is especially hazardous for historians, who often struggle to explain the past. Peering into the future is not part of their professional training, and their efforts to do so are likely to fail.

But the need to prepare for an uncertain future forces us to think ahead. For historians, the most immediate question is how COVID-19 will affect the profession of history. Though the answer depends on several things — the timely advent of a safe, affordable, and effective vaccine being chief among them — a number of changes to the profession are almost certain to occur.

One big problem facing historians is that conducting research will become more time-consuming. Unlike scholars in some other fields, historians normally have to travel to conduct their research. Archives will likely institute hygiene-related protocols, which will increase the time historians must wait to gain access to documents. Moreover, reading rooms in archives may admit fewer researchers at a time, which would involve further delays. These and other COVID-related measures could significantly slow the pace of archival research.

The additional time needed to do research will make it more expensive as well. Archives are often located in major cities, where the cost of living can be quite high. Though the current lower cost of short-term lodging reflects a diminished demand, prices will probably rise once the pandemic is under control. This could result in scholars spreading out research trips over multiple years, thus lengthening the time needed to complete dissertations, books, and articles. The tenure clock might have to be extended to compensate for this longer research process. Graduate students, who generally have to make do with extremely tight budgets, will be especially hard hit.

To compensate for shorter research trips, historians will undoubtedly seek technological solutions. The advent of the digital camera has already revolutionized research. Using a digital camera allows a researcher to photograph literally thousands of documents in a single day. Though many historians continue to do research the old-fashioned way — taking notes — they might now pick up a digital camera instead. This move could change how the profession trains graduate students in the methodology of historical research.

Closely related to this issue is the possibility that the pandemic might also push R1 history departments to move away from requiring faculty to publish books in order to receive promotion and tenure. Publishing articles, which is the standard in social sciences such as economics and sociology, may become the norm. Writing a history book often involves traveling to many archives, some of them distant from the scholar’s home base. The process can take years. However, articles can be written in much less time and without as much archival research. Diminished research budgets and the health risks associated with extended travel could persuade history departments to accept articles for promotion and tenure in place of the traditional monograph.

The pandemic will almost certainly accelerate some trends that are already underway. The number of students majoring in history has been declining for years. Majoring in history in a more uncertain economic environment might be seen as an unaffordable luxury for all but the wealthy. Rather than follow their academic passion, students may instead pursue majors that appear to provide better job prospects. The STEM fields (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) will probably be one of the main beneficiaries of this shift away from the humanities.

To survive this trend, history departments may redirect their scholarly emphasis. Rather than focusing on more traditional courses, we could see departments offering more courses on subjects such as the history of medicine and disease in order to remain “relevant.” History departments might also offer fewer courses in the realm of public history (oral history, archival studies, conservation, historic preservation, digital humanities), even though that is how historical records are preserved. The institutions that hire public historians, such as archives and museums, are suffering financially in the current time of upheaval, so they may be doing less hiring in the future.

History departments might also rethink their opposition to military history and diplomatic history. Both fields are seen as bastions of great man history, which has long been reviled in academic circles. Despite these criticisms, they remain a big draw for students. Another reason history departments might welcome more emphasis on military and diplomatic history is that the resurgence of nationalism makes expertise in these areas more relevant than at the peak of the trend toward globalization. History departments may lean in a more “practical” direction to satisfy the demand for relevancy and decide to offer more courses in these fields.

Other potential changes will affect all of higher education, but historians specifically will need to think about them. Teaching has already changed, at least in the short term. Professors are on campus less often than in pre-pandemic times. Historians may prefer to teach and meet students virtually rather than be on campus and risk becoming infected. To mitigate such concerns, campuses will undergo physical changes. Any new classrooms built will be larger in order to accommodate the same number of students, allowing students and professors to practice social distancing.

Departments will also have to alter their standards for evaluating the effectiveness of teaching. The migration from traditional face-to-face teaching to online instruction due to the pandemic will likely push departments to make virtual courses part of their permanent offerings. Yet remote learning is significantly different from the face-to-face learning experience. Teaching evaluations will have to change to account for this difference. On a related note, departments would be wise to offer their faculty and graduate students formal and informal courses on the best online learning practices.

Many colleges and universities depend heavily on room and board and tuition to fund operations. But the pandemic is already causing fewer students to live on campus, and as a result they (and their parents) are demanding lower tuition rates. This will mean less money for many academic departments. History departments will have to figure out how to avoid draconian budget cuts. The main beneficiaries of the competition for funds will undoubtedly be the STEM-related fields, which have already gained in popularity and influence. Public and private sector entities have for years been redirecting funds from the humanities to STEM. Moreover, because graduates in these fields command much higher salaries than those in the humanities, parents prefer that their children major in STEM-related fields— no doubt as a hedge against an uncertain economic future.

Changes in higher education precipitated by the pandemic could have a significant impact on the number of people who are actually working as historians and doing historical research. Professors who fall into one (or more than one) risk group might take early retirement, and universities might be inclined to go along with them, given declining enrollments. This could open the door for younger scholars to join the professorial ranks. However, because universities have been relying more heavily on adjuncts, new PhDs may not be offered a tenure track position when they are hired. The long-term decline in tenure hires is accelerating due to COVID-19.

Academic departments will not be the only campus institutions to experience cuts; libraries will as well. Building collections in specific areas is already difficult. This will become much harder in the immediate future.

Although recent racial unrest has prompted some history departments to offer more courses on African American history, ironically college campuses could become racially less diverse. The disproportionate impact of COVID on African American communities may also mean it disrupts college plans more for Black than for other students. Some Black students may think twice about going to college, at least in the near term. And if they do go, they might decide to attend HBCUs, which are less expensive and can often provide a more nurturing cultural environment. Offering courses on African American history, slavery, and colonialism to classes that are overwhelmingly white will provide awkward visuals for history departments attempting to position themselves at the forefront of diversity and inclusion efforts.

There will almost certainly be less immigration in a pandemic environment. Most wealthy nations have been limiting immigration for years, and the COVID-19 pandemic has reinforced this trend. It’s virtually certain that fewer foreign scholars will be visiting the United States. International programs, which exist on most university campuses, will find fewer students who can or want to travel overseas. Continuing education programs designed for senior citizens, which many history departments take part in, could become a thing of the past. College and university campuses will probably be much less diverse environments in the future.

There is no doubt that the longer the pandemic persists, the more probable it is that changes will occur and that some of them will be permanent. Historians need to prepare for these coming changes as much as anyone else. The longer they wait, the harder they will find it to adapt to change.

Michael H. Creswell is an associate professor of history at Florida State University and an executive editor at History: Reviews of New Books. He is the author of A Question of Balance: How France and the United States Created Cold War Europe.

The Radical History of Corporate Sensitivity Training

By Beth Blum

During these turbulent months, American corporations have responded to demands for racial justice by straining to showcase their sensitive sides. They’ve pledged, like Quaker Oats, to change offensive product names; they’ve scrambled, like Prada, nascar, and Delta, to implement emergency sensitivity workshops; and they’ve opted, like most of the major publishing houses, to hire sensitivity readers to vet new manuscripts for racist representations. Not so at the Donald Trump White House.

In a combative rebuff of this cultural tide, the Administration has elected to ban sensitivity training entirely from the federal government, calling it “divisive, anti-American propaganda” that is wasting “millions of taxpayer dollars.” Trump even encouraged his Twitter followers to “please report any sightings” of sensitivity-training initiatives, “so we can quickly extinguish!”

Social-justice activists have their own qualms about how the language of cultural sensitivity has been institutionalized. The rise of what the historian Amira Rose Davis calls “commodified corporate activism” is as often driven by a company’s fear of being sued as it is by ethical commitments. Ibram X. Kendi is likewise wary of therapeutic substitutes for concrete change. He argues in his book “How to Be an Antiracist” that we need to replace our “feelings advocacy” with initiatives that “put equitable outcomes before our guilt and anguish.” With utterly opposing motives, both conservatives and liberals take issue with the personalization of social conflict. But the original ideal of sensitivity training is more revolutionary than either side allows.

Corporate sensitivity did not begin in the Twittersphere or in the boardroom. It was born amid the intellectual ferment of the smoky coffeehouses of early-twentieth-century Vienna. The first sensitivity workshops resembled a radical therapeutic theatre that courted conflict (instead of mitigating it) and urged participants to voice their raw fears, biases, and emotions. The rise of corporate sensitivity is a story of how this shattering of social conventions (called “unfreezing” by early practitioners) ended up as PowerPoint presentations and team-building exercises for contemporary office workers.

It was in the same artists’ circles frequented by Sigmund Freud, Leon Trotsky, Gustav Klimt, and a young Peter Lorre that Jacob Levy Moreno, an editor of an expressionist magazine, planted the foundations of sensitivity training. Born to a Sephardic Jewish family, Moreno grew up in Vienna and became interested in group reconciliation as a student at the University of Vienna, where he attempted to mediate disputes between nationalist and Zionist student factions. Moreno’s subsequent witnessing of the rise of Hitler’s National Socialism only intensified his commitment to exchange and reconciliation. The existentialist writings of Kierkegaard and Nietzsche served as inspiration for his “religion of the encounter”: a philosophy premised upon a spiritual faith in the transcendent possibilities of authentic, face-to-face human contact. He distinguished his approach from the Freudianism that was popular at the time by advocating “acting” in the place of psychoanalytic talking, and emphasizing the “here and now” rather than past traumas and repressions.

Moreno’s idiosyncratic, mystical philosophy can best be conveyed through a poem of his, from 1914, which became the “prayer” of his psychodramatic method:

A meeting of two: eye to eye, face to face.

And when you are near I will tear your eyes out

and place them instead of mine,

and you will tear my eyes out

and will place them instead of yours,

then I will look at you with your eyes

and you will look at me with mine.

This startlingly graphic poem is not the best advertisement for Moreno’s literary credentials, but its avant-garde energies may be better appreciated when compared to the young Stephen Dedalus’s chant in James Joyce’s “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man,” first serialized the same year as Moreno’s incantation: “Apologise, / pull out his eyes, / pull out his eyes, / apologise.”

Though Moreno’s language was quirky, the group-therapy techniques that he pioneered were legitimate: role-playing, for instance, and the use of spontaneous interactions (or what today we’d call improv). Above all, his argument that people “can be made to be the crucial experts and investigators of any social setting of which they are a part” would become pivotal to the sensitivity-training methods that he exported to the United States.

Probably no one did more to adapt Moreno’s principles to the American office environment than the social psychologist Kurt Lewin, an early member of the Frankfurt school who fled Germany, in 1933, to become a pioneer of “action research” and the founder of the Research Center for Group Dynamics, at M.I.T. Lewin’s application of his background in gestalt therapy to humanizing the capitalist workplace set the scene for the rise of human-management theory, and his personal experiences with anti-Semitism gave him insight into America’s fractured race relations. In time, his sensitivity-training techniques were adopted by virtually every major mid-century U.S. corporation: Kodak, Ford, Western Electric, Boeing, Procter & Gamble, and more.

The invention of the sensitivity-training group is often traced to a specific evening: Lewin was running a workshop for teachers and social workers in Connecticut, where he had been hired by the state to help address racial and religious prejudice. After the participants had left, a few stragglers returned and asked to be permitted to sit in on the debriefings, and Lewin agreed. Though it was initially awkward to have the participants present, Lewin realized that the setup led to frank and open conversations. He saw the transformative possibilities of uninhibited feedback in the real time of the group session, and established the idea of the corporate T-group — shorthand for sensitivity “training group” — at the National Training Laboratory, in Bethel, Maine. His inroads into social engineering could also be put to less conciliatory purposes; Lewin was a consultant for the Office of Strategic Services and developed programs to help recruit potential spies.

The T-group, which was sometimes called “therapy for normals” — rather insensitively by today’s standards but with the intent of destigmatizing the practice — was a therapeutic workshop for strangers which would take place in a neutral locale and promote candid emotional exchange. A typical T-group session would begin with the facilitator declining to assume any active leadership over the session, a move that would surprise and disconcert the participants, who would collectively have to work out the problem of how to deal with a lack of hierarchy or directives.

It sounds simple enough, but the experience could be deeply unsettling, even life-changing, for some. As one contemporary witness of the Bethel N.T.L. workshops remarked, “I had never observed such a buildup of emotional tension in such a short time. I feared it was more than some leaders and members could bear.” The T-group promised an antidote to the oppressions of Dale Carnegie-style insincerity that dominated the business world, and, crucially, the sessions seemed to provide a glimpse of a reality in which it was finally possible to know how one was really perceived.

The critics of mid-century managerial society looked upon this new collective ethic with suspicion, countering that people were already too concerned with how they were perceived. In “The Organization Man,” a popular study of corporate conformity, from 1956, William Whyte pronounced the T-group morality an example of “false-collectivization.” His concerns were echoed by David Riesman, whose best-selling jeremiad, “The Lonely Crowd,” lamented the decline of rugged (masculine) individualism in the face of the “soft” other-directedness of professional-managerial culture. Even before these social analysts, W. E. B. Du Bois wrote about how the oppressive impressions of others were a defining aspect of disenfranchisement; this was the premise behind his famous account of the “double consciousness” of Black experience.

Lewin died young, from a heart attack, in 1947, and he did not experience the zeal with which sensitivity training would be embraced by the coming countercultural generation, as embodied by the Esalen Institute, in Big Sur, which is best known today as where “Mad Men” ’s Don Draper ends up. It was at the hot-springs retreat, on the sublime California coast, that the encounter tradition, established by Moreno and adapted by Lewin, joined forces with the “human-potential movement” of the nineteen-sixties to become fodder for weekends of hippie self-awakening.

In particular, the encounter tradition resonated with the unorthodox psychologist Will Schutz, who played a key role in bringing it to Esalen. Schutz began his career helping the U.S. Navy identify individuals who could manage in the intense group isolation of a nuclear-powered submarine. After a stint teaching in the Ivy League, Schutz invented a metric for predicting human interaction, called firo (Fundamental Interpersonal Relations Orientation), and put his stamp on the Moreno tradition by advancing his own “open encounter” movement; the “open” designated his willingness to combine encounter therapy with all manner of trends, from hypnosis to massage and meditation.

Extending the avant-garde energies with which sensitivity training began, Schutz’s handbook to open-encounter practice, “Here Comes Everybody,” took its title from James Joyce’s “Finnegans Wake.” What Schutz describes there as the Joycean ideal of “the unity of all levels of man” skeptics decried as cultish groupthink. But Joyce may well have approved of Esalen’s mantra: “Lose your mind and come to your senses.” Schutz’s seminars soon became notorious for their embrace of nudity, free love, and drugs. In his Esalen memoir “The Upstart Spring,” Walter Truett Anderson describes a Schutz exercise called “high noon”: two people in the midst of a conflict are asked to stand at opposite sides of a room and walk toward each other until they meet in the center. When they meet, they have to use their bodies to express the truth of their feelings about the other. Of course, the original “high noon” of the Western film genre, from which Schutz took the idea, usually ends up in murder.

All the same, in Anderson’s account, the prize for the “toughest encounter seminar that had been ever convened at Esalen” went to one run collaboratively by George Leonard and Price Cobbs. Leonard was a white psychologist from the South, whose youthful encounter with the terrified eyes of a Black prisoner surrounded by a white mob instilled in him a lifelong commitment to fighting racism. He implored Cobbs, an African-American psychiatrist who was co-authoring the book “Black Rage,” to come to Esalen to collaborate. They organized a storied, twenty-four-hour-marathon racial-sensitivity workshop between Black and white participants that became rancorous: “the anger rolled on and on without end” and “interracial friendships crumbled on the spot.” Finally, Anderson relates how, as the sun was beginning to rise, an African-American woman was moved to spontaneously comfort a crying white woman, and this shifted the tenor of the entire session. Though the episode could easily be read less sunnily, as another troubling instance of the oppressor requiring comfort from the oppressed, the facilitators purportedly deemed it a success. Cobbs spoke to Leonard and declared, “George, we’ve got to take this to the world.”

Cobbs’s career encapsulates the shift of sensitivity training from its literary roots to corporate argot. He was sparked by early epiphanies about Black anger and injustice, inspired by reading Richard Wright, James Baldwin, and Ralph Ellison. He admired the plot of “Invisible Man,” for instance, because “the unnamed main character’s sense of his own invisibility fans his ultimate rage into flames of self-expression. . . .” Cobbs credited Lewin’s research as a key precedent when he went on to found Pacific Management Systems, a training center for T-group leaders, and he played a role in the spinoff of diversity training from sensitivity training. His years of advising African-American businesspeople formed the basis of his guide, from 2000, “Cracking the Corporate Code: The Revealing Success Stories of 32 African-American Executives.”

In her provocative history “Race Experts,” from 2002, the scholar Elisabeth Lasch-Quinn examines Cobbs’s career as part of the larger story of how “racial etiquette” and sensitivity training “hijacked” and banalized civil-rights discourse. Quinn persuasively maintains that “sensitivity itself is an inadequate and cynical substitution for civility and democracy — both of which presuppose some form of equal treatment and universal standard of conduct,” and neither of which, of course, the U.S. has ever achieved. But the benefits of sensitivity might be easier to appreciate now that they are threatened with political erasure. The events of the past year suggest that the revolutionary, confrontational fervor behind the original encounter movement can’t be contained by the Trump Administration or the boardroom, or be siphoned off in spotty social-media activism. Political demands for less talking and more acting resume the call of Lewin’s “action research” and, before that, of Moreno’s spontaneous theatre.

In a television interview in the sixties, a prominent sensitivity-group leader, Richard Farson, likened the “here and now” of the encounter group to the creation of an “aesthetic experience.” Like going to a symphony or watching a sunset, sensitivity training, he argued, can be justified in aesthetic terms, as “something worthwhile in and of itself.” In our time, it is chiefly the instrumental, managerial uses of sensitivity training that have gained traction. But the history suggests that the aesthetic and the practical sides of the movement are not as firmly opposed as they seem — that even sensitivity training’s most practical iterations owe their origins to the literary context of Moreno’s expressionist Vienna and, via this lineage, to the avant-garde experiments of authors such as Franz Kafka, Joyce, and Ellison. The aesthetic commitment of these artists to radical, intrepid honesty offers a bracing spur to the encounter sessions — whether unplanned on the street or overplanned on Zoom – of our fractious, cultural present.

Beth Blum is an assistant professor of English literature at Harvard University. She is the author of “The Self-Help Compulsion: Searching for Advice in Modern Literature.”

The Pentagon is Missing the Big Picture on “Stars and Stripes”

By Mark T. Hauser

The Pentagon’s plan to scrap funding for the Stars and Stripes newspaper isn’t just an attack on a historic military institution. It’s ignoring the lessons the paper’s history offers for efficient operation and integrating military operations with the economic life of the nation.

In February, the Pentagon proposed slashing funding for the famed soldiers’ newspaper Stars and Stripes, a story that roared back into the news in September after its publisher reported he had been ordered to halt publication by the end of the month.

By the morning of September 4th, President Trump tweeted out his insistence that the paper would not be closing, though the Senate has not yet voted on a defense appropriations bill to resolve this issue. While veterans have raised important concerns about the elimination of an important journalistic voice independent of military officials’ control, administrators framed the paper’s closure as a budgetary issue to save $15.5 million – a seeming pittance in a department collecting over $705 billion in federal funding. If budgetary issues are truly the concern, I’d propose considering the paper’s history, which demonstrates how the paper actually can and does function as an important part of the public-private partnerships driving the country’s economy in connection with its journalistic mission.

In recent days, many articles have mentioned the paper’s roots during the Civil War, but few have described crucial developments during the First World War, when Guy T. Viskniskki, a Spanish-American War veteran and New York area journalist for the Wheeler Syndicate, argued a new paper describing the wartime experience through the eyes of rank-and-file servicemen could raise morale without becoming a form of propaganda. While training at Camp Lee outside of Richmond, Viskniskki established a newspaper for the community, one of many camp newspapers funded by the YMCA’s War Work Council. However, when he reached Europe in November 1917, Viskniskki dreamed of establishing a paper free from the oversight of his commanding officers and believed his knowledge of censorship regulations allowed him to effectively follow the rules placed on war correspondents. While Viskniskki was proud to highlight his paper’s financial successes and independence, the Intelligence Section provided the first 25,000 francs he needed to begin publication in January 1918. Viskniskki worked hard to push the paper beyond the narrow, divisional or company focus of other soldiers’ papers, rejecting calls to spin-off specialty publications for the Services of Supply because he believed a mass paper created a sense of unity spanning front and rear lines. He found his mass audience by providing troops with news of the war, tales from the home front including sports coverage, and comics, all written in a relatable, informal style. At its peak circulation near the armistice in November 1918, staffers printed 526,000 copies per issue and distributed them to readers on both sides of the Atlantic. When the paper closed shop in June 1919, the paper had even turned a profit (though Viskniskki was disappointed it was turned over to the US Treasury rather than distributed to French war orphans).

Viskniskki financed his paper primarily through advertisements, securing free assistance from A.W. Erickson in New York. The paper charged perspective buyers the very low rate of one dollar per inch, raising it to six dollars when the cost of newsprint grew more cumbersome after circulation rose over 400,000. By the third issue, Viskniskki packed the paper with ads for products including Boston Garters, Colgate dental cream, Lowney’s chocolates, Wrigley’s chewing gum, 3-In-One oil, Mennen shaving cream, Fatima cigarettes, and Auto Strop razors. These advertisements were part of a broader modernization of military culture that introduced servicemen to new consumer products. For example, military regulations required troops to maintain clean-shaven faces to create a firm seal for their gas masks, thus requiring them to carry their own shaving kits and creating a market for the supplies advertised in their paper; a 1919 survey by the J. Walter Thompson advertising firm found that 30 percent of safety razor users learned of the product in the army. Similarly, army officers estimated that 50 percent of conscripts had not brushed their teeth on a regular basis, leading them to order over 4 million toothbrushes for troops who purchased toothpaste at local canteens or post exchanges.

Staffers for The Stars and Stripes also developed tools to effectively distribute their paper amid harsh wartime conditions. The paper secured subscribers by collecting a large cash payment up front, making it easy for delivery agents to simply drop off the paper rather than manage individual subscribers’ accounts. Viskniskki relied on staffers from Hachette, a leading French publishing house, to carry papers from train stations to troops even when they were under fire. The paper’s staff also acquired ninety-one cars that allowed field agents to deliver the paper to most remote regions where their readers served. Such decisions to develop an internal distribution service predated similar efforts by leading retailers by several years, as major mail order retailer Sears only developed their own trucking service in the early 1920s. The Stars and Stripes’ distribution network was so effective they approached the Red Cross and YMCA to assist them with their pre-USO era responsibilities of delivering treats and entertainments to troops across service areas.

Viskniskki was far from the paper’s only reporter, and its large and successful staff both reinforced the paper’s reputation for independence and established contacts that would further its commercial impact long after the war. While Viskniskki conducted the reporting for the first few issues primarily by swiping official cables from the censorship office, he quickly expanded his team by identifying experienced journalists who had difficulty fitting in with their units because of their writing habits. These included Harold Ross, whose commanding officer in a railway engineering unit forwarded Viskniskki many articles Ross had drafted alongside a plea to remove the man he considered the unit’s headache; New York Times writer Alexander Woollcott, who Viskniskki knew wanted to cover the front lines; New York Tribune sports reporter Grantland Rice who transferred from artillery work mere issues before Viskniskki decided to cancel the sports page amid Americans’ increasing combat responsibilities; fellow Tribune scribe Franklin P. Adams who opined on military life in his “The Listening Post” column; and Philip Von Blon, the enterprising reporter who developed sources within the SOS and broke the Harts uniform story. These writers formed a close social circle during the war and after, particularly after Ross founded The New Yorker and recruited Woollcott as a writer, palling around with Adams in their famed Algonquin Round Table meetings, while Von Blon returned home and took a job as managing editor of American Legion Monthly. Viskniskki himself declined to capitalize on the Stars and Stripes brand he created, turning down a $300,000 offer to establish a paper in the United States. However, other staffers risked Viskniskki’s ire and marketed their connections to the paper when founding veterans’ publications such as The Home Sector.

While short-lived, the World War One-era Stars and Stripes demonstrated the features that would become hallmarks of the paper when it resumed publication in 1942. The paper’s editors relied on funding from the government and its affiliates to open its doors, and it contributed to the country’s commercial development by inspiring new distribution ideas and familiarizing troops with new products for future consumption. Such factors clearly demonstrate why Congressional leaders are right to offer continued support for a paper that has shaped the country’s economy and culture for over a century.

Mark Hauser is a Visiting Professor of History at Carnegie Mellon University, where he teaches courses on American cultural and business practices of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He is currently completing a book manuscript on public-private partnerships during the First World War and their impact on American mass culture. He resides in Pittsburgh and can be reached on twitter @markhauser.

Amtrak’s New Fall Fare Sale Lets You Bring a Friend for Free

Riding the rails is the perfect way to follow fall down the Northeast Corridor

Written by Katherine Alex Beaven

Summer may be officially over — R.I.P. — but Amtrak is already giving us reasons to get excited about celebrating fall. This week the national rail service announced a huge buy-one-get-one sale on Acela business class and Northeast Regional coach train fares. This means you can buy a ticket and bring a friend for free — or just split the difference and save 50 percent on ticket prices.

Sure, cars are great for road trips, but trains are where it’s at when it comes to the ultimate hands-free way to snag that much-needed change of scenery. Riding the rails is the perfect way to follow fall down the Northeast Corridor, from Boston to Virginia, whether it’s leaf-peeping, pumpkin patch hopping, or just winding through beautiful landscapes that are only accessible via train.

Fares are on sale through Sept. 30 and are good for travel on dates from Sept. 24 to Dec. 12, 2020. Fall foliage tour, anyone? To take advantage of these bring-a-friend fare deals that range from $30 to $129 one-way, you’ll have to book at least three days in advance. Need a reason to bite the bullet and plan ahead? Amtrak is also offering no change fees and full refunds on tickets through Sept. 30.

“The BOGO sale offers a fantastic deal for Northeast Corridor travelers, while also providing the chance to experience new amenities, and learn more about extra savings on upcoming initiatives that will upgrade the overall customer experience,” Caroline Decker, Amtrak’s vice president for the Northeast corridor service line, told TripSavvy.

If you’re concerned about safety, Amtrak has adopted enhanced health safety measures that include aggressive disinfection and cleaning protocols on trains and in stations, onboard filtration systems that replace the air on the train every four to five minutes, and booking to limited capacity and leaving middle seats open to ensure adequate spacing between passengers.

“Our efforts to deliver a new standard of travel and highlight our commitment to customer and employee safety are reflected in the expansion of Reserved Seating to Acela and Northeast Regional Business Class customers, offering peace of mind with a reserved seat and the ability to physically distance or be seated with friends and family,” Decker said.

They also require all employees and passengers wear masks that cover both their nose and mouth—anyone who doesn’t comply risks being removed from the train or station or banned from future travel on Amtrak trains. Plus, you can use the Amtrak app for a contactless ticketing experience.

The Amtrak experience is only bound to get better in 2021, as the company has a new Acela fleet in the works and looks forward to the opening of the Moynihan Train Hall, an expansion of New York’s bustling Penn Station, next year.

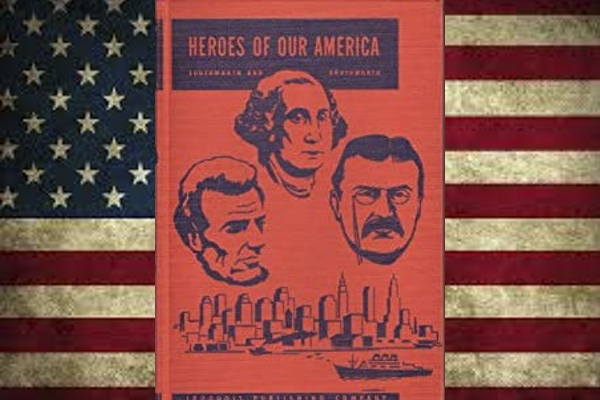

“Heroes of Our America”: Reading a “Patriotic” History of the United States

By Alan J. Singer

Not long ago, history textbooks were written as patriotic fables. Examining one offers a warning about the cost of putting mythmaking ahead of historical learning

Heroes of Our America (1952) was a history book for fourth graders published by the Iroquois Publishing Company of Syracuse, New York. Its co-authors were Gertrude and John Van Duyn Southworth. John Southworth, with Harvard and Columbia University degrees, taught at a number of schools in the New York metropolitan area and was president of the publishing company. Gertrude Southworth, his frequent co-author, was also his mother.

Heroes of Our America (1952) was a history book for fourth graders published by the Iroquois Publishing Company of Syracuse, New York. Its co-authors were Gertrude and John Van Duyn Southworth. John Southworth, with Harvard and Columbia University degrees, taught at a number of schools in the New York metropolitan area and was president of the publishing company. Gertrude Southworth, his frequent co-author, was also his mother.

I picked it off my office shelf after Donald Trump called for teaching “patriotic history” in American schools as a defense against a mythical radical “left” conspiracy and to ensure that “our youth will be taught to love America.” Heroes of Our America is an example of the kind of “patriotic history” Donald and I were both exposed to as children in the 1950s. I grabbed the book when it was discarded from the Hofstra University Curriculum Materials Center only a couple of years ago.

Heroes of Our America’s thirty-two chapters include 31 biographies starting with Christopher Columbus and ending with baseball players Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. One chapter is a collective portrait of the English settlers of Plymouth Plantation; George Washington and Abraham Lincoln get two chapters each. There are biographies of two women, Jane Addams and Susan B. Anthony, and one African American, George Washington Carver. A page on “Important Historical Holidays” lists “January 19th: Robert E. Lee’s birthday, celebrated in the Southern states in honor of the great leader of the Confederate army, who was born in 1807.”

Historical fables taught in the past at least partly explain why the issues raised about slavery, ongoing racism, and United States history documented in the New York Times 1619 Project came as such a shock to White America and engendered such steep opposition from, among others, President Donald Trump. Accepting the Republican Party’s Presidential nomination, Trump recently told his audience, “we want our sons and daughters to know the truth: America is the greatest and most exceptional nation in the history of the world.” President Trump later threatened to defund California schools if they include the 1619 Project as part of the social studies curriculum and acted to purge any reference to Critical Race Theory or White Privilege in federal government agencies, including the Department of Education.

In the preface to their book, the Southworths announce that in spite of their differences all of the people included in the book had “one great thing in common; all of them helped make our country great.” Students are asked, as you “read about these people,” to try to find out “what it was that made each person great.”

Chapter Twenty-Three is a biography of Robert E. Lee, who did “gallant” military service as a United States army officer during the “Mexican War,” became “superintendent of the Military Academy at West Point,” and captured a “strange, fierce man named John Brown” who had “seized the government storehouse at Harper’s Ferry” and was “trying to get the slaves to rise up against their masters.” Students are told that in these actions, Robert E. Lee always “put his duty ahead of his own feelings.” Eventually, as “In the life of many men there comes a time when they must choose between two things, both of which they dearly love. That time can for Robert E. Lee in the spring of 1861, when the Southern states left the Union.” Lee’s “soul struggled with the choice between loyalty to the government under which he fought and loyalty to the state of Virginia and to the Confederacy.” Lee chose Virginia, the Confederacy, and slavery and went to war against the United States, but the Southworths believe he remains a “great man” nonetheless.

George Washington Carver is portrayed as a Black Horatio Alger who succeeded through luck and hard work. In Chapter Thirty, students are introduced to “a boy who had less than any of the others. He did not even own himself, for he was born a Negro slave.” As a baby, during what the book calls the “War Between the States,” Carver was “bought in exchange for a racehorse” by a kindly white family in Missouri who treated him “almost as though he had been their own child.” Carver left the family when he was ten years old to pursue an education. Heroes of Our America leaves out that Carter was denied admission to colleges in Kansas because he was Black. According to the book, through his discoveries in agriculture he later helped “his beloved South to become rich and prosperous,” which it didn’t, especially if you were an African American sharecropper. The chapter concludes, “Everybody in the United States, and particularly everybody in the South, owes a great deal to George Washington Carver.”

The Southworths’ conclusion about Sam Houston in Chapter Eighteen summarizes their view about many of America’s national “heroes.” According to the Southworths, “Samuel Houston did many things during his lifetime. Many were good, and a few were bad. There were far more good things than bad, and the good things which he did were much more important.”

I went through the index focusing on some key terms: Africa, cotton, Declaration of Independence, Emancipation Proclamation, Indians, Negroes, Reconstruction, and slaves:

“Negroes who had been captured in Africa” landed in Jamestown in 1619. “They were made to till the soil and do all sorts of hard work . . . This was the beginning of Negro slavery in what is now the United States.”

“Many of the slaves were treated kindly and had comfortable homes, but others had little to eat and wear and had many hardships to endure.”

Curiously, students are told that “the Negroes of those days were not educated enough to work in the factories.”

Students also learn that songwriter Stephen Foster “really loved the Negroes, and used his songs to express the way he felt about them.” The chapter on Foster includes the lyrics to “Old Black Joe”: “Gone are the days, when my heart was young and gay. Gone are my friends from cotton fields far away.” Students don’t learn that Foster’s songs were performed by whites wearing black facial make-up in minstrel shows where enslaved Africans were portrayed as simple people happy in their enslavement.

Coverage of the 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debates credits Lincoln with “the wonderful way in which he had expressed the arguments against slavery,” which of course, he didn’t. In the chapter on Henry Clay, students learn “It is in no way surprising that the people of the South saw much good and little evil in the slave-labor, which was so cheap and which served their purposes so well.” People, of course, meant white people only. Daniel Webster was a “true patriot” for supporting the Compromise of 1850 with the Fugitive Slave Law.

In the biography of Abraham Lincoln, students learn that Lincoln hoped that in response to the Emancipation Proclamation enslaved Africans would “desert the Southern cause and stop their aid to Southern troops,” and that the Emancipation Proclamation gave “freedom to more than three million slaves living in the Confederate states,” which it didn’t. The Fifteenth Amendment is mentioned in passing in the biography of Susan B. Anthony, who “felt that if the freed slaves were permitted to vote, the women should be permitted, too.” Students learn about Africa in the biography of Theodore Roosevelt, who “went off to Africa on an exciting hunting trip. There he met black savages, and had dangerous meetings with the fierce animals of the African jungle.”

The Trail of Tears is missing in the book, but Indians are included as the “savage friends” of Daniel Boone and the Cherokee are mentioned as great friends of Sam Houston. Andrew Jackson “smashed” the power of the Creek Indians and defeated groups of “Indians and outlaws” raiding the United States from Florida, which at the time was controlled by Spain. In the chapter on Theodore Roosevelt, students learn “The Redmen were supposed to live on reservations, but they often left them, and they were not always friendly to the white men they chanced to meet.”

The Declaration of Independence is mentioned multiple times, but students never learn what it says. They do learn that cotton was not initially a profitable crop because “it took all day for a Negro slave to pick the seeds out of a single pound of cotton,” that was until Eli Whitney developed “a machine with which a single slave could pick the seeds from fifty pounds of cotton in a single day.” John James Audubon fled a possible “uprising of the natives against the French” in Haiti in 1789. John C. Calhoun doesn’t merit his own chapter, but in a chapter on Daniel Webster, Calhoun is described as a “real statesman” and born debater and orator. Reconstruction is described in the biography of Woodrow Wilson. Growing up in the Southern states of Georgia and South Carolina, “he was very unhappy to see the way in which the North blamed the South entirely for the war, and made the Southerners suffer for it.” These experiences gave Wilson a “great sympathy for the ‘underdog,’ and always afterwards he was anxious to do what he could to help the weak and the helpless.”

Abolitionists, both black and white, Klan terrorism, Jim Crow laws, racism, and segregation, as well as workers’ struggles for union rights, do not appear in this fictional “patriotic history” book.

Alan Singer is a historian and Professor of Secondary Education at Hofstra University, author of New York and Slavery: Time to Teach the Truth (SUNY Press, 2008) and New York’s Grand Emancipation Jubilee: Essays on Slavery, Resistance, Abolition, Teaching, and Historical Memory (SUNY Press, 2018). Follow him on Twitter.

The 5 Best Ways to Prevent a First Heart Attack

By Sharon Basaraba

Medically reviewed by Richard N. Fogoros, MD

Whether your father, mother or siblings have had heart disease may seem like the most important predictor of your own chances of a heart attack. Not so — says a large Swedish study published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology in 2014. In fact, it showed that 5 specific lifestyle factors like eating right, regular exercise and quitting smoking can combine to prevent 80% of first heart attacks.

The researchers, from the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, set out to determine to what degree healthy habits individually — or in concert — help adults avoid a future heart attack or myocardial infarction.

Rates of coronary heart disease have dropped in many parts of the world, write the authors, thanks to advances in medications that work to fight high blood pressure and lower cholesterol. Since huge populations are at risk of cardiovascular disease, however, the use of prescription drugs — with their own risks of side effects and significant cost if taken over the long term — are not an effective wide-scale preventative strategy, argue the researchers. They write that their own past research on women and that of other scientists on both genders shows lifestyle changes can dramatically cut heart attack risk.

What the Study Examined

Men between the ages of 45 and 79 were recruited in 1997, and surveyed about their eating and activity habits, along with data including their weight, family history of heart disease, and level of education. A total of 20,721 men without any history of cardiovascular disease, cancer, or diabetes were then tracked over an 11-year period.

Five diet and lifestyle factors were examined: diet, smoking habits, alcohol consumption, belly fat, and daily activity level.

What the Researchers Discovered

Each of the five lifestyle habits or conditions was found to offer its own individual benefit in preventing a future heart attack. The best odds were found among men adhering to all five—reaping an 80% reduction in heart attack risk — although only 1% of the study population was in this category.

How the Habits Ranked According to Heart Attack Protection

Quitting Smoking (36% Lower Risk): Consistent with extensive previous research, quitting smoking is one of the top longevity-threatening habits you should abandon. In this Swedish trial, men who had either never smoked, or quit at least 20 years prior to the beginning of the study enjoyed a 36% lower chance of a first heart attack.

This jives with findings of many previous investigations including the Million Women Study in the UK, in which almost 1.2 million women were tracked over a 12-year period. That longitudinal research found that quitting by the age of 30 or 40 reaped an extra 11 years of life on average, thanks not only to fewer heart attacks but less cancer and respiratory disease as well.

Eating a Nutritious Diet (20% Lower Risk): Again, no surprise that a healthy plant-based diet can help ward off a heart attack (and other age-related diseases like diabetes and cancer). The Swedish study characterized a healthy diet using the Recommended Food Score from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) in the US, which is “strongly predictive of mortality” and includes the following:

- At least 5 servings of fresh vegetables and fruits each day

- 4 servings of whole grains

- 1 or more servings of reduced-fat dairy

- Weekly consumption of about two servings of healthy fish

Those subjects who followed these guidelines most closely had a 20% lower risk of a first heart attack, even if they also ate foods from the “non-recommended” list such as red and processed meat, refined cereals and sweets.

Getting Rid of Belly Fat (12% Lower Risk): Increasingly, epidemiologists are finding waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio to be a better predictor of ill health than sheer body weight, especially when it comes to abdominal fat that surrounds your internal organs (visceral fat) and not just the pudge that sits under the skin of your belly making your waistband too tight.

Indeed, subjects in this Swedish study whose waistlines measured less than 95 cm (about 38″) over the course of the trial, had a 12% lower risk of a first heart attack compared with men with more belly fat.

Drinking Only in Moderation (11% Lower Risk): In this study, drinking in moderation cut the risk of a first heart attack by about 11%. This is in line with very consistent evidence that consuming alcohol in moderation reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease, including heart attacks and stroke.

Still, the researchers offer certain reservations about alcohol’s benefits, since as soon as consumption goes beyond light-to-moderate intakes of 1-2 drinks per day, there are far more hazards than benefits to health in the form of heart disease, cancer, and accidents.

To recap: people who drink in moderation may be healthier than teetotalers, but only if they drink in moderation.

Being Physically Active (3% Reduction in Risk): Men who walked or cycled 40 minutes per day, and exercised at least one hour per week were found to have a 3% lower risk of a first heart attack in this study. That number is surprisingly low, considering other evidence that exercise is very beneficial for heart health. Still, exercise has such strong benefits not only for your cardiovascular system but towards strengthening your bones, your respiratory system, helping ward off dementia and also stress relief (not to mention avoiding the hazards of sitting still), it should not be considered a fringe health strategy. The more you move, the better.

Did This Study Just Look at Healthy Men?

These male subjects were all free of disease when the study launched in the late 1990s. A separate analysis was conducted among more than 7,000 men with hypertension and high cholesterol in 1997, which found that the risk reduction of each healthy behavior was similar to that of men without either condition.

Bottom Line

Unlike your genetic makeup, diet, exercise and whether or not you smoke are all within your control; in science jargon, “modifiable lifestyle factors”. Such changes may not always be easy to implement, but it can be inspiring to discover that what you do each day can play a greater role in determining your chances of a first heart attack than what you inherit.

In this large study, 86% of first heart attacks were avoided by the small proportion of men who adhered to all 5 healthy habits, regardless of family history of cardiovascular disease. Generalized to the greater population, that means 4 out of 5 first heart attacks might be prevented with straightforward and manageable lifestyle changes.

California experienced another COVID-19 surge a few weeks ago. The good news now is they have flattened the curve (for a second time). San Francisco area guest author David Erskine discusses 15 holistic lessons he’s learned during the COVID pandemic in this week’s blog.

Epiphany Central – 15 Lessons from the Pandemic

Dr. Allen asked me to write a fourth blog yet again from just ten minutes north of the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco. If you read my last blog, you know that we experienced another COVID-19 surge a few weeks ago. The good news now is that California has flattened the curve (for a second time) as I write this mid-September.

So far our state has completed 26 weeks with the goal to flatten the curve, support frontline health workers and keep ourselves and our families healthy.

Literally half a year later, I thought it might be a good idea to summarize some of the lessons this pandemic has taught me – or at least reinforced.

- Practice Gratitude – Every day brings change. Embrace it.

- Commit to Daily Exercise – Not only does it clear the mind, it gives new perspective.

- Speaking of Perspective – We are in this together. Noise is just a distraction.

- Embrace Uncertainty – Accept uncertainty, and remember that it often leads to creativity.

- Give Back – Mentor three people, and share your wisdom whenever there’s an opportunity.

- Be Pro-Active – Do NOT wait for change. MAKE the change.

- Be Creative – Whether you write, paint or blog like me, create something new.

- Do Bikram Yoga – Yoga keeps me present, by forcing me to balance, focus and breathe.

- Enjoy Surprises – Every day surprises can literally cover me with joy.

- Drop Your Ego – My ego is not my amigo. The love I receive is equal to the love I make.

- Control Trichotomy – Stoic philosophy says only focus on what you can completely control. (Hey, it’s worked for 2000+ years!)

- Conquer Hate with Love – Love is about others. Hate is about ego. (See #10.)

- Laugh and Make Others Laugh – Share a joke with an essential worker, for example. I promise, it will be the highlight of the day.

- Remember that Negativity is a Drain – Literally, it’s a bottomless pit. Try to find joy, most likely in helping others find THEIR joy.

- Make Every Breath Precious – Remembering this can literally change your life.

These are my top 15 lessons. Don’t be afraid to share with us what you’ve learned in the comment section, I’d love to see more on this list!

And as always, remember our Heroes on the frontlines will live in our hearts and minds forever. Our collective will to fight systemic racism will grow in our DNA. The question remains what each of us will choose…for me Count Me In with gratitude and love!