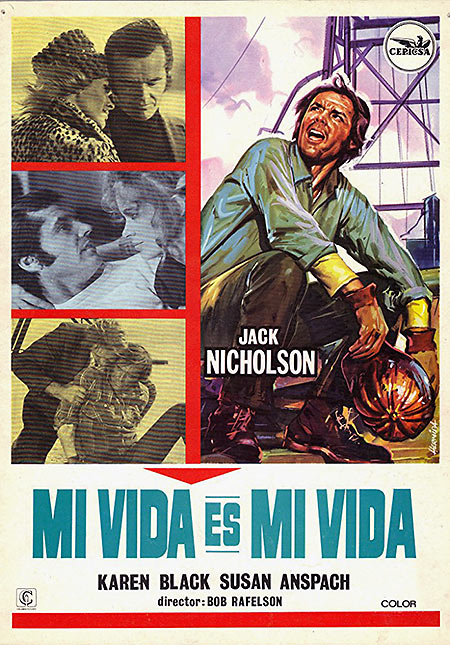

Directed by: Bob Rafelson

Directed by: Bob Rafelson

Writers: Carole Eastman (screenplay, as Adrien Joyce), Bob Rafelson (story), Carole Eastman (story, as Adrien Joyce)

Cast: Jack Nicholson, Karen Black, Susan Anspach, Lois Smith, Billy Green Bush, Ralph Waite, Sally Struthers, John Ryan

Cinematography by: László Kovács

Five Easy Pieces

By Walt Mundkowsky

Fogged with the Easy Rider air of self-defeat, Five Easy Pieces is much stronger on feelings than on insight. It’s not art but still affecting; the actors under Bob Rafelson’s direction lend a certain truth.

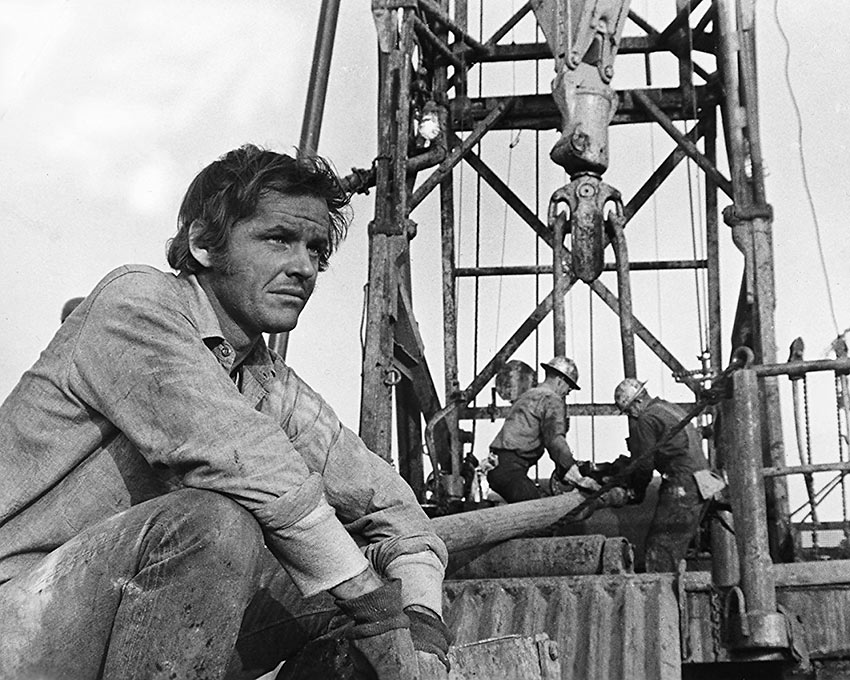

There’s no plot worthy of the name; it gives us several weeks in the life of Bobby (Robert Eroica) Dupea, a former piano prodigy who fled his aristocratic family years ago and is now working in a California oil field. He is living with a none-too-bright waitress named Rayette Dipesto who dreams of becoming a country singer. (His dissatisfaction with her and his existence is conveyed in a few keen details. Over the titles we hear “Stand by Your Man.” As Bobby comes home, he too hears the song, played on a phonograph. He pauses at the door as one might in front of an activated bomb. Once inside, he helps himself to a beer. The chorus blares forth as he walks into the living room; he stops and glares at the record player for several seconds.)

Bobby enjoys the pleasures at hand — bowling, drinking, whoring — without a hint of conscious slumming. His friend Elton confides to him that Rayette is pregnant, and “she’s all torn up about it, which I hate to see.” “I tell ya,” Elton continues, “somewhere along the line you even get to liking the whole idea.” “Keep on telling me about the good life, Elton, because it makes me puke.” Bobby storms off. Elton is taken away by the police for jumping bail after a robbery that’s a year old. It is the last we see of him.

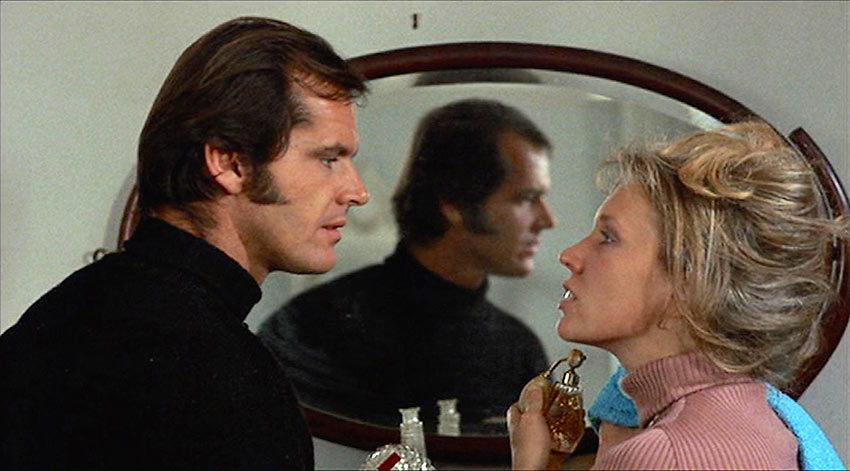

Bobby drives to a studio to visit Tita, his concert-pianist sister; she obviously worships him and hopes to convince him to return (“I want to talk to you about so many things”). In a telling shot Tita, in sharp focus, looks at Bobby, slightly blurred in the foreground; she gives him the bad news: “Robert … I have to tell you. Daddy’s very ill — he’s had two strokes.” He doesn’t want to hear about it and doesn’t want to go back, but she won’t relent — “But don’t you think it’s right that you should see him at least once?” He agrees to drive up to the family place, on an island in Puget Sound. Rayette comes along, but Bobby drops her in a nearby motel. He finds his father reduced to a vegetable state, alive but not living. (“He doesn’t even know who the hell I am,” Bobby snaps.) Also at the house are Tita; her condescending brother Carl, recovering from a painful neck injury; his fiancée and student, Catherine Van Oost; and Spicer, the ex-sailor male nurse. Mealtime conversations nearly equal scenes in Losey’s Accident — hostility under a veneer of politeness. “One thing I find very difficult to imagine is how one could have this incredible background in music and then just walk away from it without giving it a second thought.” The threat is implicit, and Bobby returns the volley: “I gave it a second thought.” He pursues Catherine and, bristling with anger, she succumbs.

Uh oh. Rayette shows up in a taxi and Bobby seethes, though the situation is of his own making. He dashes out and gets drunk. The next evening a woman invited to the house is spewing fake-intellectual gibberish and patronizing Rayette; Bobby finally explodes. Later he asks Catherine to leave with him. She sensibly refuses: “It’s useless. I’m trying to be delicate with you, but you just won’t understand.” A painful, touching monologue follows: Bobby tries to justify his life to his mute father, but keeps breaking into tears. He and Rayette leave, heading south. They stop at a gas station; Bobby examines his face in a large mirror. The process takes perhaps a minute: a tiny but detectable change of expression. He leaves his jacket behind (he has given his wallet to Rayette) and hitches a ride on a big logging truck.

What the film chooses to do, it generally does well; problems arise in what it omits. If we are to experience loss over the violence Bobby does to himself and those around him, we need to know in some tangible way what is discarded. How good a pianist might he have become? At the end of his monologue he says, “We both know that I was never that good at it anyway,” but he is defending the decision he made long ago. More important, what kind of person is he? Bobby is absent from very few shots in this movie, but much about him remains annoyingly unclear.

That monologue merits examination because, sharply written and acted though it is, it raises more questions than it answers. Bobby begins nervously (“Are you cold?”), already sounding defeated at the start (“I don’t know if you’d be particularly interested in hearing anything about me”). He thinks the very attempt is futile: “I’m trying to imagine your half of this conversation. […] It’s pretty much the way it got to be before I left. I don’t know what to say.” The key lines are: “I move around a lot, not because I’m looking for anything really, but ’cause I’m getting away from things that get bad if I stay. Auspicious beginnings, you know what I mean?” This is unrelated to what we have seen. How did Bobby meet Rayette and why has he stayed with her? What drove him away from his family and music?

Particularly puzzling is Bobby’s seduction of Catherine. She wants everything he left home to get away from; they are constantly sparring. (“Well, it must be very boring for you here.” — “It is,” he replies. — “I find that very hard to comprehend. I don’t think I’ve ever been bored.”) The scene where she rejects his offer is full of the same crackling aggressiveness, Bobby asking her impossible questions and Catherine parrying them. Earlier she seems affected, convention-bound, smug. But she is a dedicated musician; the first thing she asks him is, “You no longer play at all?” I fail to grasp why he should be so interested in her, given what we know about him, and why he should regard her as his potential savior. Her refusal to leave Carl for Bobby is the most intelligent choice any character in the film makes. She is perfectly aware of the situation: “You’re a strange person, Robert. […] When a person has no love for himself, no respect for himself, no love for his friends, family, work, something, how can he ask for love in return? I mean, why should he ask for it?”

One guesses Bobby is victimized not by the world but by design; the closest he comes to criticizing the society which traps him is in a freeway traffic jam, but none of the people he encounters is truly up to his level and many are caricatures. The two life styles — oil rig worker and concert pianist — are sketched without inside knowledge of either. Take your camera into a small town at dusk and point it at a garishly hyped nudie theater, a barber college, the nearly deserted streets with expanses of neon, the desolate headlights of the few passing cars. Slap a solo piano on the soundtrack (a wind instrument can be substituted), and you have captured indelible images of the emptiness of modern life. Five Easy Pieces has this standard sequence, and it cuts as deeply as expected (i.e., not at all).

The drive home from California is crammed with incident. The lesbian hitchhiker’s diatribe (“I had to leave this place because I got depressed seeing all the crap … people’s homes, just filth … people are filthy … I think they wouldn’t be so violent if they were clean…. I don’t even want to talk about it”) is linked thematically to Bobby’s final escape north, but outstays its welcome. Bobby’s battle of wits with a crusty waitress is also too amusing for its own good. Some of the material is arbitrarily “shaped” — it begins to involve us with interesting relationships and then patly cuts them off. Bobby and Elton walk it off after arguing, but moments later the police come to take Elton back and Bobby rushes to his aid. What would have happened between them if melodrama had not intervened?

Still, the film is frequently arresting and sometimes truthful. Lois Smith gives the most complex, inventive performance as Tita, Bobby’s sister. When she sees him at the recording studio, she bursts into tears. “You always do this to me,” she sobs. “Well, I don’t mean to,” he counters. She refuses to admit that her father’s condition is likely unchangeable (“He has ways of communicating, Robert. I can tell when he’s expressing approval or disapproval, just by his eyes”). When Bobby’s attempt to reach the old man fails, he leaves abruptly. She intercepts him, and her accusation — “You were going without saying goodbye to me” — pierces us to the heart. Karen Black’s Rayette has been overvalued; the most I can say is that she firmly resists tugging for sympathy, and brings some depth and detail to a stock role. One splendid delivery sticks — she brays at Bobby, “Why don’t you just be good to me for a change?” Susan Anspach, an actress from the theatre, is an ideal Catherine; her arresting features, at once blunt and delicate, reticent appeal and cool, edgy voice are exactly right. She gets Catherine’s maddening natural elegance with ease. With less screen time, Billy “Green” Bush (Elton) and Ralph Waite (Carl) impart openness and a sublime ability to annoy, respectively.

That takes us to Jack Nicholson, on whose Bobby Dupea the film stands or falls; it stands, sort of. One can almost hear a motor humming inside the character. The best moments are those when Bobby is not doing anything, yet his mind is clicking away. After a scene with Rayette in a bowling alley, Bobby stares down at his feet only to be interrupted by two local hookers. At the end, sitting in the logging truck, he mutters to himself, “I’m fine”; again, the same words, this time softer; he mouths “I’m fine” a third time as the truck starts up, blotting out his words. Nicholson never finds an inner consistency for the character despite the many excellent moments; but one can hardly ask the actor for what is nowhere indicated in the script. He fits into the oil field better than into the music room, especially his voice. A major performance, even if all its facets do not mesh.

I yield to many in my evaluation of László Kovács’ camerawork on Easy Rider and Getting Straight, but Five Easy Pieces is more straightforward. Not that it is wholly free of the arty: Bobby walks away from the oil field in an over-composed shot — elaborate cloud formation, row of sunspots on the lens, oil pumps Bobby walks past resembling Easter Island statues, camera position and lighting chosen to render the thing Beautiful. And one overripe sunset wouldn’t be out of place in David Lean. But most of Kovács’ work here is intelligent and understated. The editing (Christopher Holmes, Gerald Shepard) is in the same vein; transitions are generally unforced, and two of them deepen our comprehension of connections. Bobby is enticing the two pickups in the bowling alley: “I sure wish I had more time to talk to you girls, but … uh … I have to … I’ll … uh …” — cut to him walking across the parking lot to a hurt Rayette waiting in the car. Bobby chases Catherine into the house at the conclusion of some silly game, both of them laughing — cut to a similar shot, this time the camera moving in the opposite direction: A taxi pulls up to the Dupea house and Rayette steps out. The sure cutting also heightens the impact of the good performances.

Five Easy Pieces has that curse, the promising film; but it breaks its promises as it makes them. We shall have to wait and see where Rafelson and Carole Eastman (script, as “Adrien Joyce”) go from here.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.