Directed by:

Directed by:

François Truffaut

Writing Credits:

François Truffaut … (scenario and dialogue) and

Claude de Givray … (scenario and dialogue) and

Bernard Revon … (scenario and dialogue)

Music by

Antoine Duhamel

Cinematography by

Denys Clerval

Film Editing by

Agnès Guillemot

Script Girl:

Suzanne Schiffman

Cast:

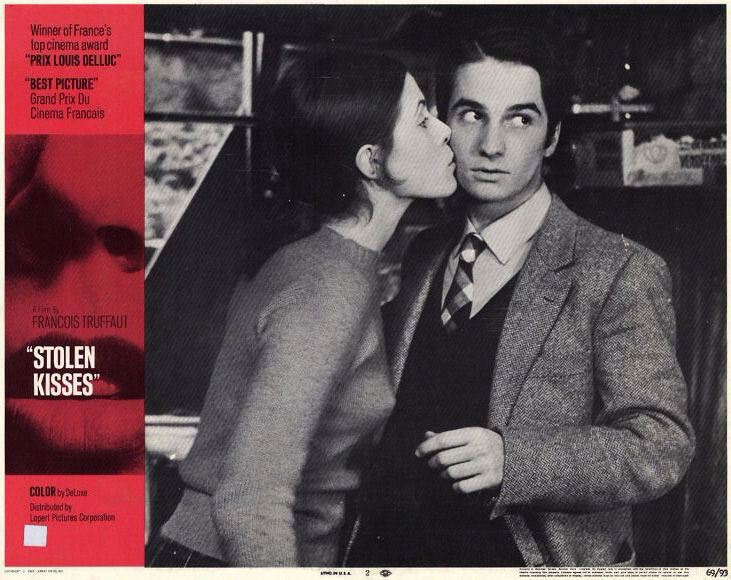

Jean-Pierre Léaud, Delphine Seyrig, Claude Jade, Michael Lonsdale

François Truffaut’s “Stolen Kisses”– A Look Back

By Walt Mundkowsky

In The 400 Blows Truffaut introduced Antoine, a 12-year-old at odds with the world in which he found himself. Antoine lost his girlfriend to an older and more masterful rival in the opening segment of Love at Twenty. Now, after two failures (not only of execution), Truffaut has returned to that character, but Stolen Kisses does not mark a reprise of his most confident style: The unsticky humor and precise observation are gone, replaced with suffocating “charm” — a vapid title song, numerous lapses into Lelouch-type romanticism, every sort of winking at the audience.

After the opening titles, the camera swoops down from a picturesque long-shot view of Paris to zoom in on a window of a military jail. Inside, Pvt. Antoine Doinel (played as before by Jean-Pierre Léaud) is being kicked out of the army only a few months after enlisting. (“Some men are hopeless,” his commanding officer tells him. “They just clutter up the army.”) After his discharge Antoine goes to see Christine, his girl, but she isn’t home; her parents get him a job as night porter at a hotel, where he is promptly fired. He joins a private detective agency, exhibiting the same knack for disaster. (“I don’t know what to do with you. You’re certainly willing, but you discourage me,” his boss says.)

One day a businessman named Mr. Tabard (Michel Lonsdale) comes in with an unusual request — “Well, nobody loves me and I want to know why … I feel that I’m despised, but I don’t know by whom. I can feel it all around me … my wife laughs all the time — except when I tell a joke.” Antoine is installed in Tabard’s shoe store to find out what his employees think of their boss. After the store is closed Antoine sees Tabard’s wife Fabienne (the beautiful Delphine Seyrig) trying on a pair of shoes. She asks him, “What do you think of these? Too shiny for the dress?” He falls for her instantly, and reports, “She’s superb, a little vague and very gentle”; her face is “a perfect oval, slightly triangular … luminous skin!” Christine is forgotten. “What do you mean, hounding me at the store?” he snarls at her when she stops by to ask why he hasn’t been seeing her. “There’s no reason to be nasty,” Christine replies, hurt.

But catastrophe is never far behind. Left alone with Mrs. Tabard, an epic case of nerves overtakes him. She plays a record — “Do you like music, Antoine?” “Yes, sir,” he gravely answers, and dashes out of the room. When he goes home later, he finds a gift and an understanding letter she has left. Antoine writes to her, and as we hear him reading his letter the camera follows its progress — tracking along underground tubes, flicking from one street sign to the next. Fabienne opens the letter and the camera pans slowly across a street, tilting up for a zoom-in on Antoine’s window; the image freezes. Fabienne goes to Antoine with an offer — “I’ll come close to you now … we’ll spend a few hours together … and no matter what happens we’ll never see each other again.”

Antoine crashes into Christine’s father’s car; he is now a TV repairman. Christine’s parents leave for the weekend; she sabotages the TV set and phones for Antoine. He is cool when he arrives, but his resistance is understandably brief. Truffaut’s camera moves past TV parts scattered on the floor, past Antoine’s work timer, and tracks slowly up the stairs, finally coming to rest on the young lovers asleep in bed.

The next morning Christine and Antoine go for a walk. They are confronted by a mysterious stranger who has been following her throughout the picture, to the accompaniment of a throbbing bass. “I know I’m not unknown to you,” he begins. He has come to confess his undying love: “We’ll never leave each other, not for a single hour … you will be my sole preoccupation.” He glares at Antoine, “But first you must separate from some temporary people.” As he leaves, Christine says, “The man’s really mad!” “Yes, yes,” Antoine agrees, suddenly recognizing his true self. “He must be.”

Truffaut cannot resist his hero as an adorable, romantic, shy incompetent. Applied this conspicuously, charm repels. A freeze frame of Antoine’s “disarming” smile reveals the extent of the miscalculation. Later, blundering attempts at tailing people are conveyed by peering over a newspaper of course held upside down, or peeking out from behind a tree. And the Truffaut of 1960 wouldn’t have milked the death of a veteran private detective (long shot of rows of tombstones; the camera panning down to follow Antoine leaving the cemetery with music rising on the soundtrack).

Stolen Kisses has no real plot; the episodic impression is heightened by the liberal use of fade-outs. This could have worked if the writers (Truffaut and two others) had constructed dense, economical sketches, but nearly everything is trivial; we trail Antoine for 91 minutes, but Truffaut has nothing more to say about him. The old Truffaut pops up here and there. Having lunch with Tabard and his wife, Antoine mentions that he’s learning English with records. “Records are a joke,” Tabard snaps. “You can only learn English in bed with an English girl. I learned with an Australian; her husband was a house painter —” “Comme Hitler,” Fabienne interrupts. “Don’t ever say that,” he warns. “It’s slander. Hitler was a landscape painter.”

For a Truffaut film, Stolen Kisses is visually stale. In the past he has always used the best cinematographers — Henri Decaë on The 400 Blows, Nicolas Roeg on Fahrenheit 451, Raoul Coutard on the rest. Even his worst films have contained flashes of poetry. Here, Denys Clerval’s DeLuxe color camerawork is far from lyrical and equally far from obnoxious. The editing of Agnès Guillemot is unobtrusive and apt. But Antoine Duhamel’s music is poured over each scene like molasses: It has about that consistency.

I’d rather blame Léaud’s man-child affectations on Truffaut, but the actor’s antics have done similar harm elsewhere. Only Seyrig’s distinctive looks and personality are evident in this tritely conceived part. Claude Jade delights as Christine, a mixture of innocence and cunning, and Michel Lonsdale plays the friendless Tabard with a stern, straight face that is very funny.

Stolen Kisses can hardly be said to settle anything about Truffaut’s career: He is only 37 and this is but his seventh feature. But he is covering familiar ground — no striking observations, resonances, or stylistic expression. If the result is more successful than Fahrenheit 451 or The Bride Wore Black, it’s because Truffaut risks so little these days.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.