Directed by: George Lucas

Directed by: George Lucas

Writing Credits:

Story by George Lucas

Screenplay by George Lucas and Walter Murch

Produced by:

Francis Ford Coppola … executive producer

Edward Folger … associate producer (as Ed Folger)

Larry Sturhahn … producer (as Lawrence Sturhahn)

Music by: Lalo Schifrin

Cinematography:

Albert Kihn … director of photography

David Myers … director of photography

Film Editing by: George Lucas

Cast:

George Lucas’ THX 1138

By Walt Mundkowsky

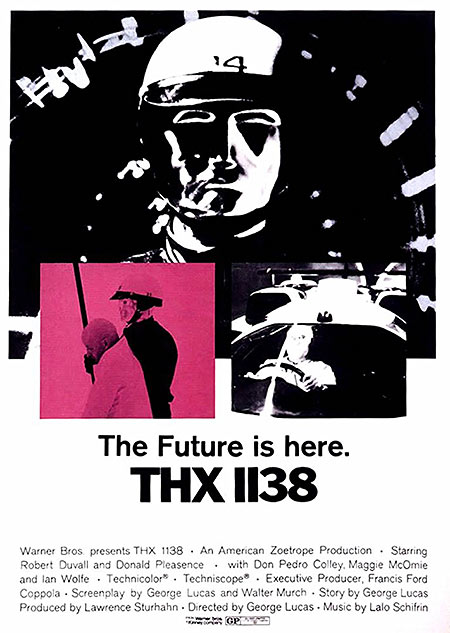

In 1967 George Lucas, a student at the University of Southern California, made Electronic Labyrinth THX 1138 4EB, a 15-minute short about a computerized society; it won a National Student Film Award and Warner Bros. financed its expansion into this feature. (EB stood for Earth Born.) THX 1138 has problems but it establishes Lucas, at 25, as someone to follow.

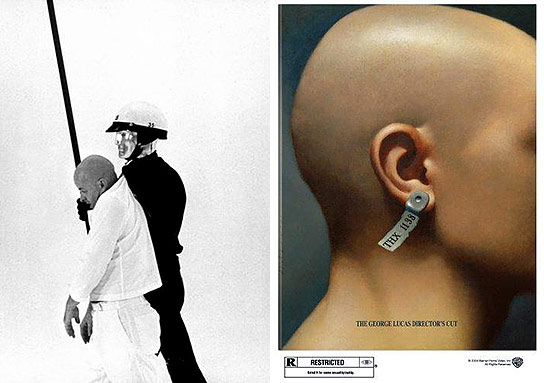

The script (by Lucas and Walter Murch, from Lucas’ story) is the largest hang-up. This futuristic world is the usual batch of clichés: the all-powerful State, with its cheery announcements and imposing, shiny robot police; numbers rather than names, identical uniforms, shaved heads; chemically produced babies, sex (read love) is outlawed, etc. THX 1138 comes 39 years after Brave New World and 22 after 1984, and not one of its ideas wasn’t used to greater advantage in those classics.

Making an anti-technology film on a level this naïve is like making an anti-shrubbery movie. Even in light of the simplistic plot, the assault looks misguided. The hero escapes the society with a cunning application of the technology at hand. That eventual ending is fake: It’s an escape to the earth’s surface — the entire “world” turns out to have been underground — and THX stands motionless, as if mesmerized, in front of an enormous sinking sun. Now what?

The dialogue also contains numerous lines that strain to comment on our own times. The tape-recorded voice urges THX , “Buy more. Buy more now. Buy. And be happy.” Nobody in the film is ever seen buying anything. Lucas has not found his way to the center of his story, and I see little reaction to the possibilities of the future as we can perceive them in the present, which Elio Petri’s The Tenth Victim (1965), for all its pop-art excesses, certainly has.

Lucas also has little rapport with his actors. Robert Duvall (THX) has been an uncommonly interesting performer in other roles, but here similar opportunities are absent; he would be stronger if the dialogue and direction gave him a chance. Donald Pleasance would seem ideal as a shifty-eyed worker (“You know, I have a way with computers — I can program myself for almost any area”), but his accent and technique separate him from the rest. A San Francisco actress named Maggie McOmie, with crewcut red hair and freckles, is highly attractive as LUH 3417, the hero’s roommate and lover. Her part is small, but if the hero’s flight is to affect us much, she has to cast a shadow over the remainder of the film. Much-needed levity comes from Don Pedro Colley as a hologram who’s planning his own escape.

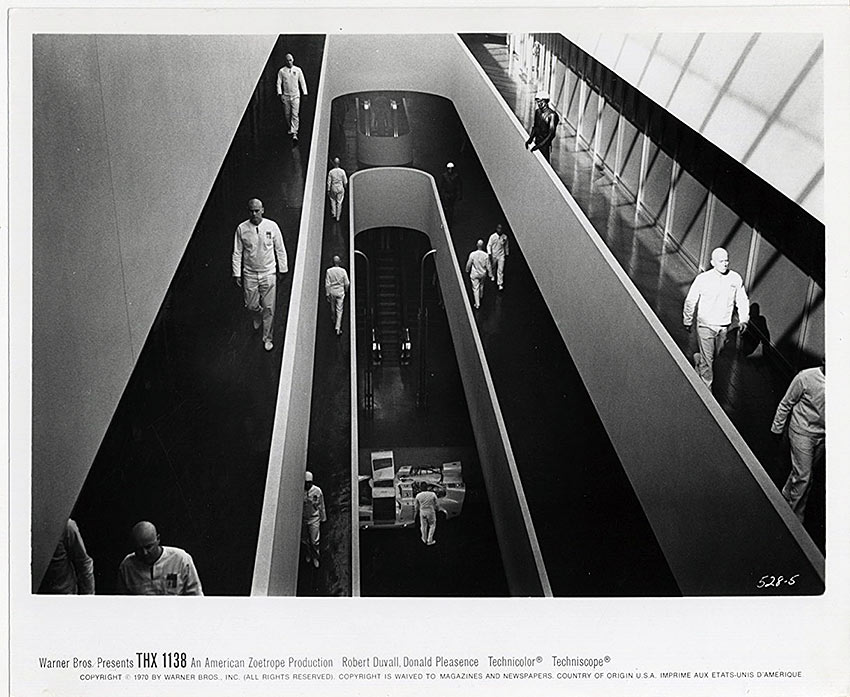

The first few minutes (after a horrendous Buck Rogers film clip and the credit titles unrolling in the opposite direction, down instead of up) are superb. Numbers flash on the screen, quick cutting with sections of black film spliced between shots. A TV-screen image, grainy and tinted blue, of LUH (as we later learn). “What’s wrong?” a voice asks. “Nothing. Nothing, really.” A series of rapid-fire computer printouts. Another TV image; it is THX 1138. “What’s wrong?” “Nothing, I … never mind.” A control panel lights up as buttons are pushed. Reassuring messages fly off the soundtrack: “Take four red capsules. In 10 minutes take two more. Help is on the way!” “For more enjoyment and greater efficiency, consumption is being standardized. We are sorry.” Slogans multiply: “Keep up the good work and prevent accidents.” Then we hear that “this shift is concluded.” THX leaves his post and takes an escalator which leads into dazzling whiteness. Long, brightly lit white corridors. THX goes into a booth, like confession. The responses he receives have been recorded in advance: “Very good … yes, I understand … I … yes … yes, I understand … yes, I … excellent … yes … could you be more … specific? … You are a full believer … let us be thankful we have an occupation to build.” THX goes to his apartment and watches the wall-size TV — sex, violence, stand-up comics. “You know, I don’t feel well,” he says. “Take a sedation,” LUH suggests. She is sick in the bathroom and the solicitous announcer reminds her, “Remember, an Interval overdose may cause a serious chemical imbalance.” THX is worried about her; he tells the confessor, “Just an ordinary roommate. I share rooms with her; our relationship is normal, conforming. We share nothing but space. What is she doing to me?” So far Lucas has kept everything brilliantly controlled; I would like to know more about this society than THX knows, but within that limitation the first part convinces.

But once THX and his hot-blooded friend get going, clichés stack up like firewood. She tells him after they make love the first time, “I was so afraid. I’m so alone. I wanted to touch you — so many times.” Later the Orwell vibe kicks in. “They’ve been watching us. I can feel it,” she says. “No one knows,” he counters. She: “They’re watching us now.” He: “No one can see us.” No soap opera could survive without this complaint: “If you go back on sedation, you won’t feel the same way about me. You’ll report me for drug violation.” “I wouldn’t turn you in, not now.” Later he tells her, “It can’t go on forever. You know it can’t.” Had Lucas approached the affair simply, it might have worked. But when they are lying together naked and still, discovery by the police is certain. One moment, though, has power. On the run, THX locks himself in a computer room and asks the apparatus what has happened to LUH. The information appears onscreen: “LUH consumed (21 89). Number reassigned to foetus,” followed by its number. A picture of new foetus LUH 3417. The terrible anonymity of her death is shattering because it isn’t pushed at us, in marked contrast to other matters.

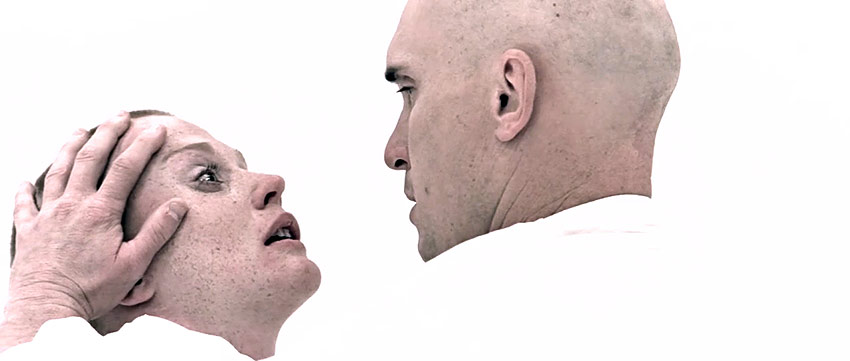

Lucas has an eye for striking photographs which advance the story. The Technicolor – Techniscope work of Dave Meyers and Albert Kihn is superior; I find the basic visual motif, the white-uniformed humans against blindingly white backgrounds, fascinating and poignant: disembodied heads and hands making their way across the screen in impregnable solitude. Especially fine are the extreme long shots — most of all, LUH walking towards THX for the last time, her head a speck in a sea of white. Lucas redeems a few photographic commonplaces simply through execution. Few recent films seem to have been made without the telephoto shot of a speeding auto or plane plowing lingeringly through the liquid haze. THX 1138 contains such a maneuver, with THX in a cop’s stolen vehicle — in the distance, surrounded by the blackness of the tunnel, a shimmering collection of revolving, flashing lights, out of focus; the lights sharpen as they roll closer; at last they turn into a Lola T70 which whips past us.

Lucas has an eye for striking photographs which advance the story. The Technicolor – Techniscope work of Dave Meyers and Albert Kihn is superior; I find the basic visual motif, the white-uniformed humans against blindingly white backgrounds, fascinating and poignant: disembodied heads and hands making their way across the screen in impregnable solitude. Especially fine are the extreme long shots — most of all, LUH walking towards THX for the last time, her head a speck in a sea of white. Lucas redeems a few photographic commonplaces simply through execution. Few recent films seem to have been made without the telephoto shot of a speeding auto or plane plowing lingeringly through the liquid haze. THX 1138 contains such a maneuver, with THX in a cop’s stolen vehicle — in the distance, surrounded by the blackness of the tunnel, a shimmering collection of revolving, flashing lights, out of focus; the lights sharpen as they roll closer; at last they turn into a Lola T70 which whips past us.

A mobile camera is seldom employed; the abrupt cutting patterns, fast and disrupted at the start and slowed down later on, are wholly responsible for the film’s urgent sense of disquiet. Lalo Schifrin’s music is a step above his norm these days — long, groaning passages for strings or organ, an occasional furtive flute, electronic beeps and whines — and is cleverly used.

THX 1138 is just good enough to leave questions about its maker. George Lucas knows how to put a film together; what he seems to lack, at least here, is a reason for making one. I defy anyone to describe him to me on the basis of this; it has finesse but little personality. We shall see if Lucas is more than a skilled technician.

The official music video for Peter Gabriel’s “I Have the Touch,” off his 1982 Security album, features extensive clips from THX 1138. On YouTube.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.