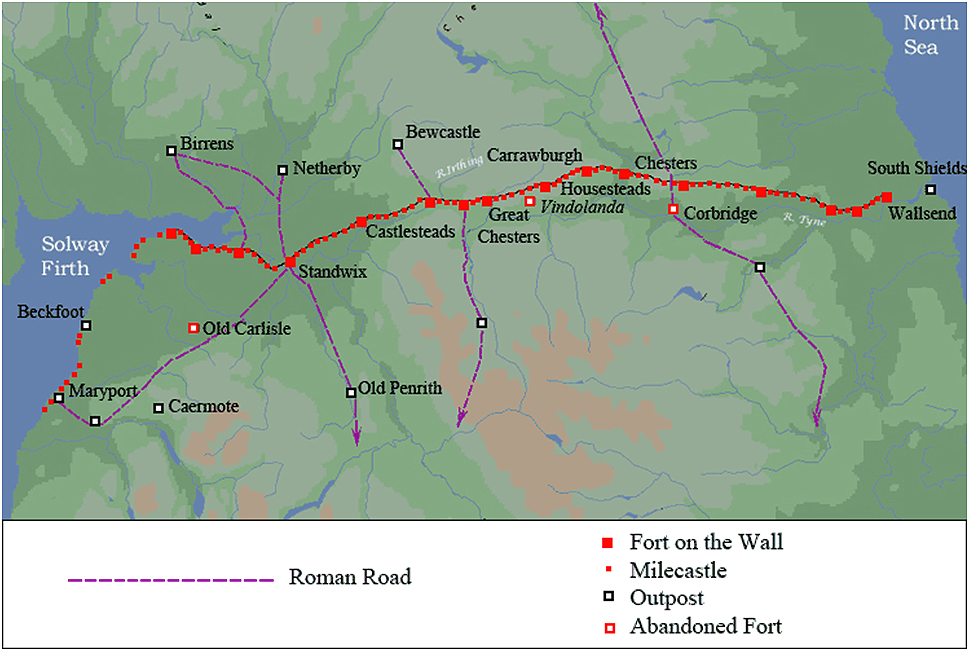

What can be said that has not already been said about Hadrian’s Wall: A marvel of Roman ingenuity, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the last frontier of the Roman Empire. A stretch of 73 miles of stones from sea to sea, covering the entire width of the island of Britannia, from Wallsend on the River Tyne in the east to Bowness-on-Solway in the west. A Wall once believed to be 15 ft. in height and 6 ft. deep with large forts and smaller mile castles and intervening turrets. It took six years of work by skilled Roman engineers and masons, along with thousands of auxiliary soldiers, to build. Upon its completion, the Wall was fully manned by approximately 10,000 Roman soldiers to protect the Roman province of Britannia, Imperial Rome’s final province and frontier, from the barbaric Caledonians of the north.

The Wall was not only intended as a defensive structure, protecting the civilized Roman world from the unconquered barbarians in the north, but stood as a testament of Rome’s will and might. It was a propaganda statement, but also served as a census bureau, for the Romans were meticulous record keepers, and wanted to know who was in and who was out. It was the equivalent of a modern-day protection racket, for each person who would pass through the wall was taxed; you were protected, but you would have to pay for it. And tax and trade were among the many things that defined the Roman Empire.

But now, my real education, an oral one, of the history of Hadrian’s Wall would begin by booking a personalized tour with the passionate tour guide extraordinaire, Mr. Peter Carney. My day commenced with Mr. Carney driving us 16 miles from North West England’s city of Carlisle, to a place where locals simply refer to as the Wall. His narration began almost immediately, explaining why Hadrian’s Wall was built, what it did and how it changed the course of human and technological history. But this piece of history does not begin or end with the Wall; it’s as much about the history of the Roman Empire as well as the world we live in today.

The Wall That Bears His Name

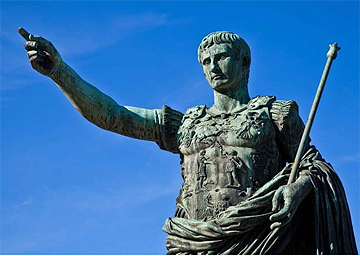

Caesar Traianus Hadrianus, Roman emperor from 117 to 138 ACE, was known for his travels throughout the empire, devoting much of his time to civil and military constructions. He was considered to be a benevolent dictator as his interventions generally went unchallenged. And this included building projects, in particular, building projects in which he had designed. Prior to the advent of Hadrian’s Wall, he constructed the Arch of Hadrian in Athens, the Temple of Venus and Roman Arch of Hadrian and rebuilt the Pantheon in Rome. Many of the world’s most famous structures and monuments may lay claim as an homage to others, but were also intended to be an homage unto oneself, where the wealthy have branded their buildings with their own names and logos, even more so today. No lists required.

Hadrian had drawn the design for his Wall without ever having visited the new Roman province of Britannia before. Prior to his arrival, the province had suffered a major rebellion (119 to 121 ACE), comprising some 3,000 soldiers. This might have had something to do about his arrival in Britannia in 122 ACE, but most sources have indicated that it was really more for him to see the early construction of his Wall and then to revise it, and perhaps revise it again.

It was a herculean task to construct the Wall, almost unimaginable in its day, where Roman masons and auxiliary were relentlessly challenged by harsh windswept fields, wide rivers and rolling hills that were not conducive to Hadrian’s initial plans. But Hadrian and his builders, like the Roman Empire itself, could not be stopped, making brilliant use of local geographical features. The well-known Central Sector ran 12 miles along the crags, with the east Wall placed on a long ridge running eastwards to Newcastle, while the west Wall was often located on shorter ridges, allowing views of the north to improve the mobility of the army in the event of Celtic attacks in the frontier.

There is still no conclusive evidence to determine when Hadrian’s Wall was actually completed. An inscription suggests that at least one part of Wall was finalized around 128 ACE, six years after Hadrian left Britannia. He never saw what is believed to be the finished Wall, the Wall that bears his name… but his name and Wall will always remain the same.

Julius Caesar and Britannia

The first direct Roman contact with Britannia began when Julius Caesar undertook two expeditions in 55 and 54 BCE, believing the Britannic people were helping the Gallic resistance in what is today’s France. The first expedition was more of a reconnaissance one than a full invasion, only gaining a foothold on the coast of Kent, a county in South East England, unable to advance further due to storm damage to his ships. Despite what he thought was a failure, it was a political success, with the Roman Senate declaring a 20-day public holiday in honor of Caesar’s achievement of obtaining hostages and pacifying small tribes. The second invasion involved a substantially larger force where Caesar coerced many of the tribes to pay tribute in return for peace. This concluded with the surrender of the warlord, Cassivellaunus, and the installation of the more Roman-friendly king, Mandubracius. Caesar conquered no territory and left no troops behind, but established new trade partners and brought Britannia into Rome’s sphere of influence.

Remember Vindolanda

The Vindolanda site today contains a modern world-class museum using the latest interpretation techniques which convey the mysteries of Roman life at the Wall. The Vindolanda Writing Tablets, thin slivers of wood covered in unique Latin scribble, were found in the oxygen-free deposits, buried beneath the wooden fort’s floor. They are the oldest surviving handwritten documents in Britain.

In 2018 the museum was extended with an underworld gallery, housing collections of 2,000-year-old artifacts, which included everything from a wooden toilet seat to a children’s toy sword.

It could be a cold and lonely life for a Roman soldier stationed at Vindolanda, where heavy rains and chilling winds would often be a daily occurrence. Many of the solders had arrived from the warm climate of the highy populated Italian Peninsula, and for new Roman commanders and their families, it was akin to a blunt slap in the face in comparison to their early life of luxury in the capital city of Rome.

Vindolanda has attracted archaeological attention for more than a century, but many mysteries still surround it. Students and amateur archeologists volunteer their time and money for digs and lodging during the summer, but often never make it in due to the long list applicant

Claudius, the last person considered to be an Emperor

Emperor Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus was born August 10 BCE at Lugdunum (modern Lyon, France). He was the first Roman Emperor be born outside of Italy, and was ridiculed throughout his life by speaking a rustic form of Latin. His pedigree came from the Julio-Claudian dynasty; Claudius from his father’s side, Julian from his mother’s side of the family. The mocking Claudius received upon speaking rudimentary Latin was not unusual, for he had been ridiculed most of life. At a young age, due to sickness, he had a limp and slight deafness, and was ostracized by his family and kept hidden from the Roman aristocratic eye. In a sense, this was was good for him, for potential enemies did not see him as a serious threat, thus saving him from the fate of assassinations and purges of earlier powerful Romans. By the time of Claudius’ adolescent years, his physical symptoms seemed to subside, and Rome’s senators and patricians began to notice his intelligence and scholarly interests. Nevertheless, Claudius did he best to remain out of view, pleased that there was no hope for advancement, which was exactly what he did not want.

But the new emperor, Caligula, his relative, did recognize Claudius to be of some use as a historian, and appointed him as his co-consul in 37 ACE to inflate the memory of Caligula’s deceased father, Germanicus. After Caligula’s assassination, despite Claudius hiding as an act of survival, he was declared emperor by the Praetorian Guard, as the last adult male of his family.

As an emperor, Claudius was considered to be fair and and efficient. He constructed new roads, aqueducts and canals across the Roman empire, and restored its finances after the excesses of Caligula’s reign. He issued new reformations; ranging from the mandatory death of a slave owner who kills his own slave, to public flatulation, believing it will lead to a healthful life.

But the manifestations of Claudius’ new physical condition were difficult to ignore: his head shook and his body buckled under weak knees. He slobbered and stammered when under stress, making his speech almost incomprehensible. Historians assume his stress was from the fear of his own assassination. Several coup attempts had already been made during the first year of his realm, and he was aware that it could happen at any moment. And so he did everything in his power not to offend his armies; rewarding the Praetorian Guard with coins and tributes, and resorting to bribery to secure loyalty. One of the major themes of the Roman Empire was expansionism, and Claudius made an important calculated decision: keep the generals busy and hide them from the Roman capital by sending them off to distant lands to conquer. And one of those distant lands was an island off the western coast of Europe which Julius Caesar had named Britannia.

In 43 ACE, Claudius sent the general and politician, Aulus Plautius, with four legions to Britannia, under the guise of an appeal from an ousted tribal ally. Claudius himself traveled to the island after the completion of initial offensives, bringing with him a massive army and reinforcements, which also included elephants, an unknown beast that had a demoralizing effect on the enemy. Claudius knew that no people could ever withstand the might of the Romans with their highly trained centurions, legionaries and auxiliary who would march into battle with precision, as a unit in tortoise shell formations, using advanced technical warfare, so advanced that the Celts had never even seen such a force before. It was akin to a Martian landing for the local tribes, witnessing Roman legionaries jumping from their fleet of vessels into rough waters, and then swimming fully dressed in heavy steel armor, carrying swords and supplies, prepared to battle the second they walked on the shore.

Emperor Claudius, whose dominionship began in 41 ACE, was murdered by poison in year 54, perhaps due to a conspiracy between the senate and the Praetorian Guard, but some assumed it was by his 4th and final wife, Agrippina.

The Final Conquest

The Roman conquest of Britannia finally ended under the command of Gnaeus Julius Agricola in 84 ACE, with the Roman armies’ slaughter of the Caledonians at the Battle of Mons Graupius. Celtic casualties were estimated to be upwards of 10,000 and about 360 on the Roman side. The battle ended the forty-year conquest of Britannia, a conquest that saw approximately 250,000 Celtic people killed. Thus, the new province of Romano-Britannia was officially born with Aulus Plautius as the first governor of the new province.

Things Change

From 43 to ACE 410, in the Roman province of Britannia, all people became Romanized and enjoyed the full rights of Roman citizenship. And Britannia’s former landscape, which had once consisted of broken paths, crumbling stick homes and savage Celtic warriors with only blue tattoos covering their bodies, became endowed with Romano-Britannic culture. Their world transitioned to a network of 1,500 Roman roads, some still used today, leading to well-planned city centers and forums with monumental architecture held together with the Roman invention of concrete. Fountains, bathhouses, arenas for music, plays and poetry flourished throughout the new province. Aqueducts fed new homes with running water for bathing, indoor sewage, and some with heated floors. And through trade, Rome’s new citizens would be introduced to unknown spices, unique tools and mechanics. People who lived in rural areas discovered new forms of agriculture, grains and advanced methods of farming. In times of famine, it was no longer necessary to raid a nearby tribe or neighbor to survive.

The new Romanized people were allowed to live and travel wherever they liked without any form of confliction, as did Roman citizens who settled in Roman Britannia, bringing new ideas and new cultures from the far corners of the empire. And they were all protected by the Wall which Hadrian had built.

Roman Emperor Constantine I: The Edict of Milan

In the year 313 ACE, Roman Emperor Constantine I, along with the Emperor Lininius, who controlled the Balkans, issued the Edict of Milan, a proclamation that promised religious tolerance and freedom to be a Christian to all of citizens of Rome. Constantine kept his word, where he himself converted to Christianity, and became known as the ‘First Christian Emperor,’ though many assumed he didn’t actually understand what it meant. Nevertheless, he is venerated as a saint in Eastern Christianity, and considered responsible for introducing this new religion to mainstream Roman culture, a culture who had once thought Christianity was just another new Jewish cult, this one dedicated to a man named Jesus who had once lived in an obscure part of the Roman world. Now, when new Christianized Roman legionaries arrived at the northen frontier, Christian Crosses were embedded on their shields, and the soldiers were morally shaken upon finding that the barbarity of druids, the high Celtic priests, actually preformed human sacrifices. As Rome transition Britannica to Christianity, as they had done to much of the known world, Constantine transitioned the Christian day of worship to Sunday.

Antonine’s Wall

Antonine’s Wall was a turf wall built on stones, initially intended to be Romano-Britannia’s furthest northern defense fortification and replace Hadrian’s Wall. But it was abandoned eight years after completion, when the Roman legions withdrew to Hadrian’s Wall in 162 ACE. The Caledonians north of the Wall were never fully defeated or occupied. The Roman sentiment was basically: ‘Why even bother with these savages, there’s really nothing up there anyway.’ Today tours are readily available to Antonine’s Wall, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

And in the end…

The Romano-Britannic province all seemed to work until it didn’t, when most of the Roman army pulled out to deal with far more important matters, such as to curtail invasions in Germania from the Franks, the Alemanni, the Goths and the Sarmatians, who stood at Rome’s doorsteps. The Western Roman Empire, whose empire had once spread from the damp gray of Britannia to the deserts of Arabia and to the river banks of the Nile, would eventually fall and become another empire, the Holy Roman Empire, with the Frankish king, Charlemagne, as its emperor.

The Romano-Britannic citizens were left with a scattering of Roman military with little real form of real protection from which would soon come from the remaining barbaric Celts in the north, the war-like Vikings of Scandinavia, the conquering pagan Saxons and Angles from Germania, endless tribal wars, a new Germanic language and a new Germanic name for their island: Angland.

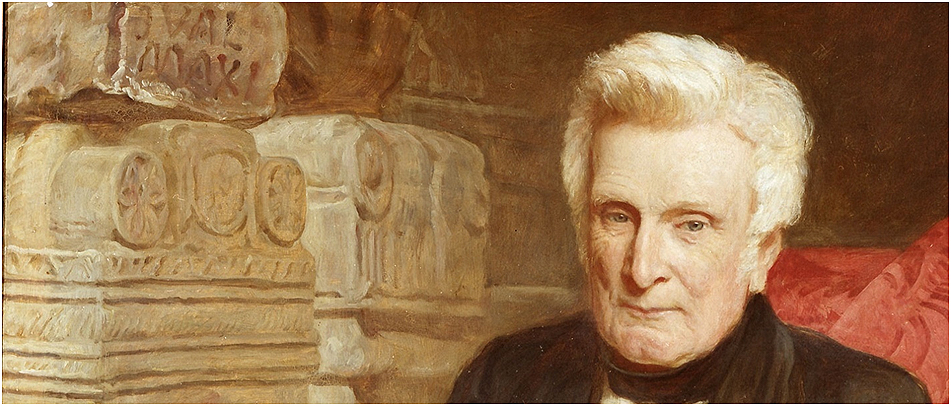

John Clayton: The Savior of Hadrian’s Wall

John Clayton (1792-1890) was a lawyer, an antiquarian and the town clerk of Newcastle-upon-Tyne. During Clayton’s youth, his father purchased an 18th-century country mansion in Humshaugh, Northumberland, adjacent to Hadrian’s Wall. The ruins of the 2,000-year-old Roman fort, Cilurnum, ran through its front garden. Clayton enjoyed exploring and digging around the fort to the point of becoming an amateur archeologist. But, he became annoyed upon seeing local people loading the Wall’s stones into wheelbarrows for reusage in constructing their own buildings. This was not unusual for much the world was built from reusage, which included the stones and marble from the Roman Forum that helped build the Rome and Vatican City of today. But for Clayton, when his own stones were taken from his own property, it was something he could not bare.

John Clayton, due to his successful lawyer-ship, had become wealthy and began purchasing large portions of the Wall and forts, and preserved them by placing sods of grass on their top. At the time of his passing, Clayton owned five forts as well as most of the Wall within 20-miles of his residence. I was informed by Mr. Carney that when we see contemporary maps dotted with English city names that end with: ‘-caster,’ ‘-cester’ and ‘-chester,’ it is an indication that the city was once the site of a Roman military camp or fort. Another example how the Roman world still affect us today.

Perhaps this obituary about John Clayton says it best:

He strove to become the Wall’s possessor. By purchasing these sites, he brought them under his protection. He stopped quarrying near to the Wall, forbade the use of Roman stone for new buildings, and moved buildings away from the archaeology. Today, he’s remembered as ‘The Savior of Hadrian’s Wall.’

Hadrian’s Wall Guided Walks with Peter Carney

Below is not a paid sponsorship for a Peter Carney Hadrian’s Wall Tour. It is an important suggestion to join one of his tours, and your memory will be enhanced, just as mine has, where the memory of my own tour is carried with me each day.

Contact:

pe*********@ha***************.com

Website: www.hadrianswall-walk.com

POST SCRIPTUM: A few things that Julius Caesar left to the world

July, the Julian Calendar, Czar / Kaiser/ Cezary in Polish / Cezar in Romanian / César in French and Spanish / Caesarism / HMS Caesar / Caesarsboom (Caesar’s Tree).

For the Caesar Salad, however, it’s best to swing down to Old Mexico and visit Caesar’s Restaurant in Tijuana, and you’ll see its birthplace and how it was created by the Italian immigrant, Mr. Cesare Cardini, ninety-nine years ago. Here’s the history of Caesar Cardini’s Iconic Caesar Salad by T-Boy Food Critic, Audrey Hart.

‘Hail Caesar’ is a phrase that was used in the Roman Empire as a greeting, a way of showing respect to Julius Caesar. But after the phrase traveled to Germany and transition to ‘Heil Hitler,’ it appears to be less popular today.

PPS: Barbarian

You might have noticed that I use the term, ‘Barbarian,’ a number of times in the text. I’m aware that once a new word or names goes out to the world, over time it takes on a new meaning with different people. I studied the etymology of ‘Barbarian’ within the context of the Roman Empire. It means, during the life of the Imperial Western Roman Empire, any person regardless of race, religion and ethnicity was branded a barbarian if they did not adhere to Greco-Roman culture. But, looking at the name within the context of the ancient Athenian world, it means: any person who did not speak Greek, spoke an incomprehensible language which sounded similar to a noise that a sheep makes: ‘bah bah, bar bar, barbarian.

To see the first three installments in the series, visit:

What’s New and Old in London, Part I

What’s New and Old in London, Part 2

What’s New & Old in England’s North

Arnold

December 7, 2023 at 11:38 am

Fascinating piece. I heard of “Roman’s Road” but I never heard of “Hadrian’s Wall.” And to think that 10k soldiers were just sitting there and guarding that … makes me wonder how many more Roman soldiers were out there conquering more lands.

The Romans, the Greeks, the Babylonians, etc. — there was so much fear living during those times. Comparing that with today’s unrest — why do people always have something to complain about? Don’t they know a good thing when they have it?

Ronald

December 7, 2023 at 11:41 am

I think I’m gonna watch Gladiator again.

Sandra

December 7, 2023 at 11:41 am

Great stuff! Well researched!

Eric

December 7, 2023 at 2:13 pm

‘bah bah, barbar, barbarian.’

Reminds me of the Beach Boys!

Very informative article Mr. Boitano. Thanks for the history lesson.

Question: So it was the Romans who originated the country name “Great Britain?”