Why the collaboration between singular songwriter and maverick filmmaker Robert Altman remains the perfect Cohen movie soundtrack

By TIM GRIERSON

In early 1971, Leonard Cohen was still a relatively unknown singer-songwriter. Despite releasing two critically acclaimed records – 1967’s Songs of Leonard Cohen and 1969’s Songs From a Room – the Canadian artist, who previously plied his trade as a novelist and poet, had yet to tour the U.S. He was then living on a farm in the small town of Big East Fork, Tennessee while preparing the release of that March’s Songs of Love and Hate. “I had a house, a jeep, a carbine, a pair of cowboy boots, a girlfriend … a typewriter, a guitar,” he once recalled. “Everything I needed.”

One day, he decided to go into town and check out a movie. He eventually decided on Brewster McCloud, a bizarre comedy about a Houston kid (played by Bud Cort) who wants to fly. The movie was a commercial and critical flop; Cohen saw it twice that day. “It’s a very, very beautiful and I would say brilliant film,” he told Crawdaddy! in 1975. “Maybe I just hadn’t seen a movie in a long time, but it was really fine.”

HYPERLINK BELOW

That night, the singer-songwriter traveled to Nashville to do some studio work. While there, he got a phone call: “This is Bob Altman,” the voice on the other line said. “I’d like to use your songs in a movie I’m making.” Cohen was flattered but had no idea who this guy was: “Is there any movie you’ve done I might have seen?”

Altman mentioned his smash success M*A*S*H, which Cohen had missed. The filmmaker then said, “I also did a small movie that nobody saw — Brewster McCloud.” As Cohen later recalled to Altman biographer Mitchell Zuckoff, “I told him, ‘I just saw it this afternoon — I loved it. You can have anything you want.’”

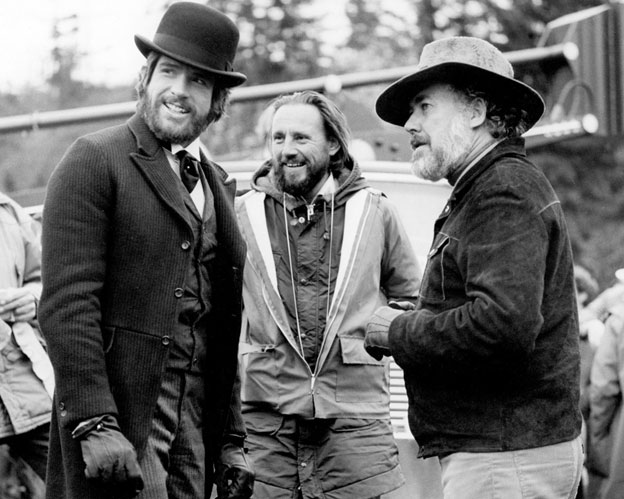

Thus began one of the great pairings of film and soundtrack of the modern era. The movie Altman was making was McCabe & Mrs. Miller, which legendary director John Huston would later reportedly proclaim the greatest Western ever made. It’s certainly one of the most visionary, with Altman transforming Edmund Naughton’s novel into a sad, beautiful tale of the American dream playing out in Washington State at the turn of the century. A luckless schemer named John McCabe (Warren Beatty) encounters the enigmatic madam Constance Miller (Julie Christie) in burgeoning, rustic Presbyterian Church, and these two entrepreneurs’ destinies are soon to be intertwined.

In much the same way, Altman’s and Cohen’s legacies would forever be linked by McCabe. The movie is inextricably connected to Cohen’s songs. It’s impossible to imagine Altman’s masterpiece without them.

The poet-musician may not have been familiar with Altman, who died in 2006, but the director certainly knew the songwriter – the iconoclastic auteur loved Songs of Leonard Cohen when it came out. “[W]e’d put that record on so often we wore out two copies!” he once professed to film scholar David Thompson. “We’d just get stoned and play that stuff. Then I forgot all about it.” When Altman started dreaming up McCabe, he drew inspiration from Cohen’s music — without realizing he had. After shooting the film and moving to the editing stage, he happened to hear some Cohen for the first time in a while and had a revelation: “‘Shit, that’s my movie!’ … [B]ack in the cutting room we put those songs on the picture and they fitted like a glove. I think the reason they worked was because those lyrics were etched in my subconscious, so when I shot the scenes I fitted them to the songs, as if they were written for them.”

Altman initially inserted about 10 Cohen tracks into the film, eventually settling on three tunes: “The Stranger Song,” Sisters of Mercy” and ‘Winter Lady.” But as musicology professor Gayle Sherwood Magee suggests in her book Robert Altman’s Soundtracks, the lyrics to other Cohen songs certainly seem to presage McCabe plot points — specifically, “Suzanne” (which describes a woman with details that are emulated in Mrs. Miller) and “One of Us Cannot Be Wrong” (which references a “blizzard of ice” reminiscent of McCabe’s snowy death after he runs afoul of a mining company). Even when you don’t hear Cohen’s music gracing scenes, the songwriter’s spirit pervades the film.

This indelible trio of tracks, all of which appear on the first side of Songs of Leonard Cohen, served as McCabe’s musical themes. “The Stranger Song” drifts over the film’s opening credits as McCabe comes to Presbyterian Church on horseback. Before we’ve even been formally introduced to our antihero, Cohen paints a picture of this mournful man as a cardsharp (“It’s true that all the men you knew were dealers”) who has a mysterious past (“I told you when I came I was a stranger”) and is seeking sanctuary (“He was just some Joseph looking for a manger”).

The second, “Sisters of Mercy,” enters the picture when we meet Mrs. Miller’s prostitutes, Cohen’s gentle song echoing the characters’ warmth and generosity: “They were waiting for me when I thought that I just can’t go on … you won’t make me jealous if I hear that they sweetened your night.”

The final track, “Winter Lady,” is Mrs. Miller’s theme, expressing the devotion McCabe feels for this woman who’s captured his heart, even though he knows any sort of meaningful relationship is impossible. “Traveling lady, stay awhile / Until the night is over,” Cohen sings, unwittingly providing an inner monologue. “I’m just a station on your way / I know I’m not your lover.” If “The Stranger Song” ushers us into McCabe, then “Winter Lady” — which plays over the closing credits — is our farewell to the movie and the man, who ends up lying dead in a snowdrift, never to see his better half again.

But it wasn’t simply the lyrical allusions that made Cohen’s music so perfect for McCabe. Just as Altman lived to subvert genre clichés and incorporate unconventional filmmaking techniques — such as his inspired use of overlapping, sometimes muffled dialogue, which gave his scenes a sophisticated, lifelike texture — Cohen was his own brand of maverick, crafting a unique sound by using nylon strings on his guitar that distinguished him from other folk singers of the time. “It’s essentially a Spanish style,” Cohen music arranger Javier Mas revealed in Anthony Reynolds’ book Leonard Cohen: A Remarkable Life, later adding, “He has got that nice tremolo playing that makes an incredible sound in his songs.”

Cohen’s desire to go his own way also provoked him to recruit the string band Kaleidoscope, which mixed folk, bluegrass and Middle Eastern sounds, to provide the distinctively exotic musical backing for Songs of Leonard Cohen. Their searching, haunting instrumentation lent his songs their elusive, wistful power — although, as pointed out by music critic Robert Christgau, the film version of “The Stranger Song” differs from the stripped-down album rendition, emphasizing the band’s musical flourishes as Cohen had intended before his producer nixed the idea.

In McCabe, Cohen’s aural landscape is an ideal compliment to brilliantly dreamy cinematography. Vilmos Zsigmond remembered in Robert Altman: The Oral Biography that when they first sat down to discuss the movie’s visual strategy, Altman “described it in images, very old, like antique photographs and faded-out pictures, not much color.” Using that at his guide, the Oscar-winning cameraman developed a technique, now known as flashing, which gives film an underexposed, grainy quality that’s akin to looking at old photos. Zsigmond’s worn images unknowingly mirrored Cohen’s spectral tunes — they felt timeless but also idiosyncratic and trailblazing. No Western had ever looked or sounded like this.

Altman has said that with this moody Western, he was trying “to illustrate a heroic ballad. Yes, these events took place, but not in the way you’ve been told. I wanted to look at it through a different window, you might say, but I still wanted to keep the poetry of the ballad.” It’s reminiscent of something John McCabe mumbles to himself while thinking of his beloved: “I’ve got poetry in me,” he insists to her, even though she’s not there to hear it. “I do, I’ve got poetry in me. I ain’t going to put it down on paper. I ain’t no educated man. I got sense enough not to try it.”

McCabe and Mrs. Miller‘s beauty and poignancy comes from the attempt to put that poetry onto the screen in gorgeously hazy visuals and piercingly sad ballads that transport the viewer to a bygone world — an old, violent America frontier that was soon to be snuffed out and tamed in the name of manifest destiny. That beauty and poignancy are even more acute now that its two main progenitors for its sound and vision are no longer with us.