Director: Lindsay Anderson

Director: Lindsay Anderson

Writers: David Sherwin (Screenplay);

David Sherwin & John Howlett (original script: “Crusaders”)

Cinematography: Miroslav Ondrícek

Sound Department: Christian Wangler (sound recordist), Alan Bell (dubbing editor), Doug E. Turner (dubbing mixer)

Cast: Malcolm McDowell, Richard Warwick, David Wood, Christine Noonan, Rupert Webster, Robert Swann

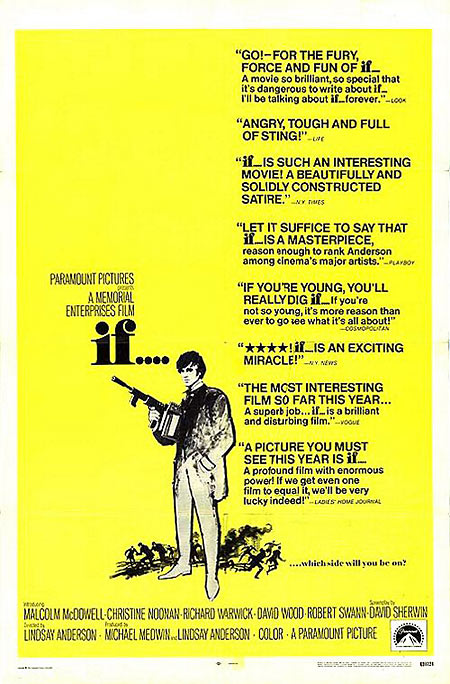

If….

By Walt Mundkowsky

“Not a failure of technique — he clearly has forgotten more about film technique than many perfectly acceptable directors ever knew — and certainly not a failure of intelligence. But a failure, if you like, of instinct. He has brilliant ideas within films, but what seems to be lacking is a comprehensive unifying idea of each film as a whole: the marvelous individual shots never quite add up to a coherent, consistent way of looking at things through a viewfinder. His films are a fascinating, because extreme, demonstration that as far as sheer intelligence can take one, there is still something more, something beyond an infinite capacity for taking thought.”

John Russell Taylor wrote that about Peter Brook, but it applies even more to Lindsay Anderson and If…. (Paramount), his second feature. This Sporting Life, Anderson’s first, had large virtues (powerful acting, assured technique, excellent sense of locale) and equally strong defects (pasting Resnais fragmentation on a naturalistic story, jarring symbolism, a whole considerably less than the sum of its parts). If…. shows his two sides even more sharply divided; it is less good, ending in confusion.

A new term starts at College House, the symbolic English public school, and Anderson and writer David Sherwin brilliantly sketch in the class structure — the younger students, or “scum”; the sixth-formers; the authoritarian prefects, known as “whips.” Mick Travers is a rebellious sixth-former (“It’s Guy Fawkes back again,” a classmate sneers); with his friends Johnny and Wallace he sets out to defy, however trivially, the authority of the whips. The smooth headmaster gives his whips a pep talk: “You could say we were middle-class … we must not expect to be thanked.” Meanwhile Mick contents himself with talking revolution — “The whole world will end very soon … there’s no such thing as a wrong war: Violence and revolution are the only pure acts. War is the last possible creative act.” In an earlier scene (the best in the movie) we have seen the intellectual powers of our heroes. A history professor (Graham Crowden) — sleepy-eyed and bored in church, an eccentric who rides his bicycle into class — questions his students, the three rebels included: “Do you disagree? Don’t you find this view of history facile? No? Do you have a view?” Silence is rarely more thunderous.

Rowntree, the head whip, decides to punish Mick and his friends for their “general attitude.” “There’s something indecent about you, Travers,” says Denson, a junior whip who looks remarkably like a hawk with spectacles, “the way you slouch about.” “I serve the nation,” he continues, fingering a military patch on his blazer. Mick snaps, “You mean that bit of wool on your tit?” He receives ten strokes instead of the usual four, and degrades himself further by shaking Rowntree’s hand and thanking him. Afterwards Mick resolves to fight. At a war games exercise he bayonets the chaplain — cut to the headmaster in his office saying, “I take this seriously.” Congealed surrealism follows. The headmaster pulls the chaplain from a drawer and tells the boys, “Now I want you to apologize to him, is that clear?” They do as they are told and the chaplain is shut away. Given another chance, the trio finds a pile of weapons while clearing some rubbish — and are joined by a mysterious girl Mick met earlier in a café.

On Speech Day a pompous general’s address (“We still need loyalty; we still need tradition. If we look around the world today, what do we see — we see bloodshed, confusion, decay”) is interrupted by smoke rising from the floor; the crowd rushes outside, into the gunfire of Mick and his mates from — a beautiful touch — the chapel roof. The shooting stops as the headmaster comes forward, “Boys, boys, I understand. Listen to reason and trust me. Trust me!” The girl shoots him between the eyes. As the firing resumes, a booming, stately organ all but drowns out the carnage, stressing the unreality — Last Year at Marienbad with firearms. A close-up of the smoking muzzle of Mick’s Bren gun — cut to a close shot of Mick, his face rigid with hate, firing into the camera — at us.

If…. is presented in eight episodes, with a chapter title on the screen preceding each one. As might be expected, this bow to Brecht leaves a lot of loose ends: Rowntree gives Bobby Philips, a blond scum (“He gets a little lovelier each day”), to Denson to see if he is homosexual; Mick and Johnny steal a motorcycle; Denson catches Wallace in the armory. We never find out how these events are resolved. The random black-and-white sequences which crop up in this color film mystify to no purpose. (Anderson has stated the reason was budgetary, not aesthetic.)

Many of the problems revolve around the shifts from reality to fantasy and back. The battle scene falls into the yawning gap between real and surreal — too sloppily observed for the former (the preceding cast is mostly absent), too ordinary for the latter. It has scant relation to what has gone before, and lacks a credible point of view through which the fantastic might be understood. Malcolm McDowell is a magnetic Travers, but cannot make him the unifying force he should be.

Anderson’s miscalculations and obtuse symbolism (Mick offers the housemaster’s wife a phallic bottle at lunch and asks, “Do you need this, Mrs. Kemp?”) ruin his best effects, shafts of delightful absurdity (Denson announcing to his troops at the military exercise, “We will attack and destroy that tree”). Sherwin’s script is much the same — short on internal development but often sparkling and wickedly pointed.

The picture is technically exciting. All praise to sound recordist Christian Wangler, dubbing editor Alan Bell, and dubbing mixer Doug Turner for what is perhaps the most precise and subtle soundtrack this side of Blow-Up. Sound is sometimes suspended, sometimes magnified; and when the sounds of Mick being beaten by Rowntree are carried over the fragile beauty of a microscope slide, an indelible image of brutality results. Marc Wilkinson’s sparse, tingling music makes room for the Congolese Missa Luba (a favorite of Mick’s) to contrast with English tradition. David Gladwell’s editing of the scene where Bobby watches in awe as Wallace swings from the bar is poetic; it consists of 13 shots, each cut arriving unexpectedly. After Wallace has dropped from the bar and our view, a gym instructor off-screen calls out, “Come on, Philips,” signaling the end of a fleeting, exquisite vision of freedom. The direct, functional camera style (Miroslav Ondrícek) has one glaringly arty shot — a punished scum hanging over the toilet, the camera flipped on its side. Wallace playing guitar in the next stall punctures it effectively. Framing of shots is up and down, as often commonplace as it is inventive.

The sadists are portrayed with more talent than their victims, as was the case with Schlöndorff’s Der junge Törless. Robert Swann’s Rowntree is smugness given breath, and Hugh Thomas boils over with malice as Denson. Not much need be said of the rebel followers: David Wood (Johnny) displays a well-developed smirk; Richard Warwick (Wallace) is appealingly disturbed. Rupert Webster has the right vulnerable mien for Bobby. Peter Jeffrey comments on the headmaster as he plays him — a dangerous tactic, but he brings it off. The character is sublimely ignorant, both comical and destructive.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.

Bryan Fleak

January 31, 2021 at 7:47 am

Great film but it’s Michael Travis not Travers.