PHOTO BY BENGT NYMAN, VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS / CC BY 2.0.

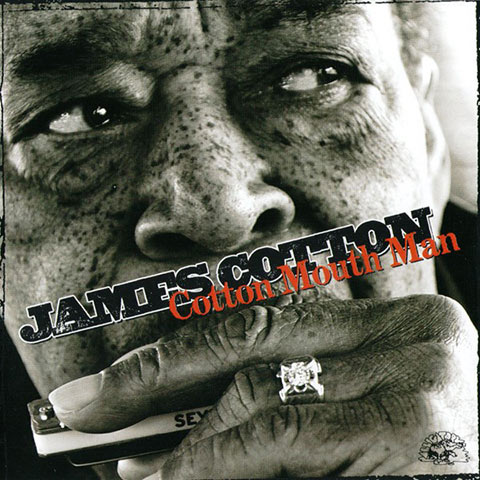

James Cotton was born into a Mississippi farming family in the middle of the summer, 1935. As the youngest of eight children, his prospects in the Tunica cotton fields held few opportunities beyond hauling water buckets for laborers or endless hours on a plantation tractor seat in the sweltering Delta sun. Fortunately for all of us, fate and a fifteen cent harmonica placed James in exactly the right place at exactly the right time.

It was an uncle who would coerce the young Cotton to walk up to, and play his harp for, radio personality Rice Miller (Sonny Boy Williamson II) Then there was the small radio spot that turned into a recording session in Memphis for Sam Phillips in the pre-Elvis era of Sun Studios. Oh, it gets better… Junior Wells would quit Muddy Waters’ band in the middle of a southern tour, forcing an immediate search for a replacement harp player. That search ended in Memphis, when Muddy met James. A meeting that began a musical collaboration and friendship that would last decades.

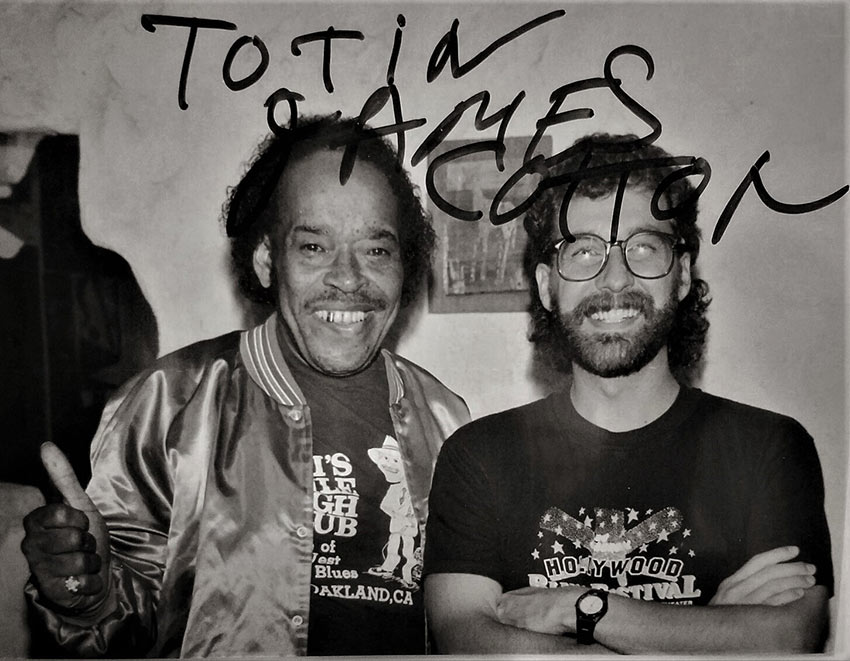

Soft spoken unless it concerned his music and extremely humble, Cotton rarely talked of his awards, Grammy nominations, or his status on the worlds blues stage. He was just a bluesman and his focus remained solely on his music. Our conversation took place backstage at a club in Southern California in the late 80s and began with his early influences in music.

“I used to listen to people.” James said. “Like Memphis Minnie and Charlie Patton. And it was Sonny Boy who kinda’ taught me how to play the harp. Sonny Boy #2, Rice Miller.”

Didn’t you live in Sonny Boy’s house? “Six years!”

How did that happen? “Well, Sonny Boy was on station KFFA in Helena, Arkansas. He had a fifteen minute program everyday from 12:00 to 12:15. I used to listen to it every day. We get out in the field with the radio and listen at that.

My uncle, me and him drove tractors together. He taught me how to drive a tractor when I was a kid. We was getting three dollars a day for driving a tractor. Get paid $36 every two weeks.

So he’d taken me to Helena to meet Sonny Boy. I told him I was orphaned, my uncle told me to say that. I walked up to him and he talked to me, you know? Me and him (Sonny Boy) got to talking, so he took me in. My uncle talked to him also when he seen it was working, you know?”

After your move to Memphis, other than Sonny Boy, who else were you playing with? “Howlin’ Wolf, Willie Love… I played with quite a few people down there.”

Any special memories of those Beale Street years? “Somebody stole my harps one day, that’s what!” (laughing) Somebody stole your harps? Who stole your harps? “I don’t know man. They were hard to come by, too! You couldn’t make no money… I had about ten of them. They ripped me off!”

Did you play a lot on the streets? “Yeah I played on the street a little bit. Not much because I was lucky enough to be in a band with Sonny Boy and we were working pretty good.”

Some folks refer to the blues as a comforter, you ever feel that way? “Well, blues do a lot of things for you, you know? Sometimes they make you sad, sometimes they make you comfortable.” What do they do for James Cotton? “They do a lot of things for me. They make me… they make me cry.” They make you cry? He nods, “Sometimes they make me cry.”

You moved to Chicago in 1954? “Had a job with the late, great Muddy Waters. Muddy brought me to Chicago. He’d been on tour, down through the South and Junior Wells left the band. Muddy was looking for a harp player and he heard about me in Memphis. So when he was coming up from Florida, he came through Memphis and asked me if I wanted a job.”

What was it like playing in Muddy’s band? “Well, I had a beautiful time playing with Muddy. I had the pleasure of working with Muddy twelve years. I had a really good time; he was like a father to me. I learned a lot of things in that band.” Like what? “He was doing a lot more recording than Sonny Boy was. A lot about the studios, things like that.”

One of my favorite albums is Muddy at Newport in 1960. You and Muddy with Tat Harris, Otis Spann, Andrew Stevenson and Francis Clay. What do you remember about that recording? “Well, I got fired the same day!” You got fired? “We did a song called, ‘I Put a Tiger in Your Tank.’ Muddy forgot the words to it and I played the lines and he said I played it wrong!” Did that happen a lot? “About a dozen times, but I always got hired back. I was lucky. I was always trying to do more, you know? Trying to make it better. A lot of things I was doing, by me being younger, Muddy didn’t understand.”

What were regular recording sessions like? “It was beautiful in the studio. But I guess he’d been doing it so long, when I got with him, you know?”

Chess provided a good environment? “Chess had got hip to the blues, man. I have to say this about the Chess brothers. I’ve never been in the studio where they recorded harmonica like the Chess brothers did. They were good at that!”

What do you suppose made them so different? “I don’t know some magic they had with those buttons back there.”

You had recorded at the famed Sun Recording Service in Memphis too, didn’t you? “I did four sides for Sun. This was before Elvis Presley or anybody like that. I did the recording in 1950, but I think it come out in ’51. Uh, I did four sides for them… ‘Straighten Up Baby,’ ‘Oh, Baby,’ ‘Hold Me in Your Arms’ and ‘Cotton Crop Blues.’”

You think you can still find copies of them? He just smiles, “Cost you a lot of money!”

You knew Little Walter? “Little Walter was a beautiful cat, man. I had the pleasure of working in Chicago with him four or five years before he died. I don’t thinks nobody will ever be better than Little Walter. I think he’s so far ahead of his time, you know?”

During the 60s, you played a lot of Fillmore dates. “Well, we probably worked at the Fillmore’s more than any band I know. Fillmore East, Fillmore West, Fillmore East… man, we did that so much till I thought I was going to die between San Francisco and New York!” (laughing) You know that those venues and events introduced blues to a whole new generation of fans, that’s quite the legacy. “I don’t even worry about things like that.” He shrugs. “I just want to be a good musician, do the best I can with it.”

Any one particular Fillmore event that stands out for you? “Yeah, I worked a date with Janis Joplin at the Fillmore West and we were managed by Albert Grossman. And then Monday she was in the office and said, ‘Look, I want to work with this guy again, he makes me work like hell.’ She said, ‘I can’t play around whenever he’s working, so I have to work!’ So, I did quite a few dates with Janis Joplin.”

Are you still having fun playing? “The music does as much for me as it does to the people out there. It makes me get up and go, too.”

How long have you been on the road? “40 years!” Ever get you down? “Well, when it ain’t fun no more, that’s when I quit. I’m certainly not getting rich, so when it ain’t fun, I’ll have to go home then.”

James went home March 16, 2017, he was 81 years old.

As a Defense Information-trained broadcast journalist and photographer, the road has taken him from the Far East Network in Tokyo, through the jungles of Central America, across the airwaves of Southern Europe to his final posting as the Chief of Radio and Television Sports for the global facilities of the American Forces Network. From on-air and studio production work in Hollywood to aerial photography from the open door of a Huey helicopter, Mr. Mattox has a wealth of experience in broadcast journalism. During his military career, he shot classified footage of Honduran air strips and landing zones expressly for Senate Sub-Committee hearings. He wrote, voiced and produced the AFRTS music series, 'The Straight, Natural Blues' portions of which now reside in the Library of Congress. He has written blues biographical features and taken photographs that have been published in multiple national and international magazines.

As a Defense Information-trained broadcast journalist and photographer, the road has taken him from the Far East Network in Tokyo, through the jungles of Central America, across the airwaves of Southern Europe to his final posting as the Chief of Radio and Television Sports for the global facilities of the American Forces Network. From on-air and studio production work in Hollywood to aerial photography from the open door of a Huey helicopter, Mr. Mattox has a wealth of experience in broadcast journalism. During his military career, he shot classified footage of Honduran air strips and landing zones expressly for Senate Sub-Committee hearings. He wrote, voiced and produced the AFRTS music series, 'The Straight, Natural Blues' portions of which now reside in the Library of Congress. He has written blues biographical features and taken photographs that have been published in multiple national and international magazines.