Director: Dalton Trumbo

Director: Dalton Trumbo

Writer: Dalton Trumbo (novel), Dalton Trumbo (screenplay)

Cinematography: Jules Brenner

Music: Jerry Fielding

Special Effects: Dick Williams

Stars: Timothy Bottoms, Kathy Fields, Marsha Hunt, Jason Robards, Diane Varsi, Donald Sutherland (As Christ), Dalton Trumbo (Orator), Winston Churchill (Himself – archive footage)

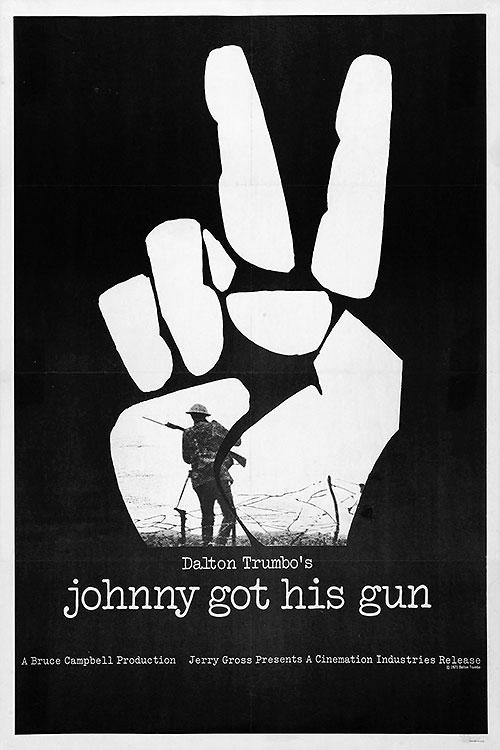

Johnny Got His Gun

By Walt Mundkowsky

The praise that has rained on Dalton Trumbo’s Johnny Got His Gun has a desperate ring, citing it with All Quiet on the Western Front and La Grande Illusion in the roll call of antiwar classics. Trumbo, of course, was one of the Hollywood Ten, refusing to cooperate with the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1947 and eventually imprisoned for 10 months for contempt of Congress. To see this film as short of towering greatness is evidently to be a HUAC assassin.

However highly one values Trumbo’s personal integrity, his profile as a writer is another matter. Pauline Kael aptly described him as “the leading exponent of the dictates-of-conscience and the dignity-and-indomitable-spirit-of-man school of screenwriting.” I can’t think of a Big Theme he or Stanley Kramer hasn’t botched. This film is no different: From the start clichés fall like well-cut pines. Above the credits is a typical newsreel montage, accompanied by the usual snare drums: shots of W. W. I leaders — a young Churchill, Clemenceau, Czar Nicholas II, Marshal Foch bestowing an embrace on a soldier, King George V, Kaiser Bill; troops and cavalry pass in review; Woodrow Wilson waves, Teddy Roosevelt makes a speech, Wilson signs papers. Over a shot of Yank soldiers boarding a ship, the whistle of an incoming artillery shell. We see the explosion and the screen goes black.

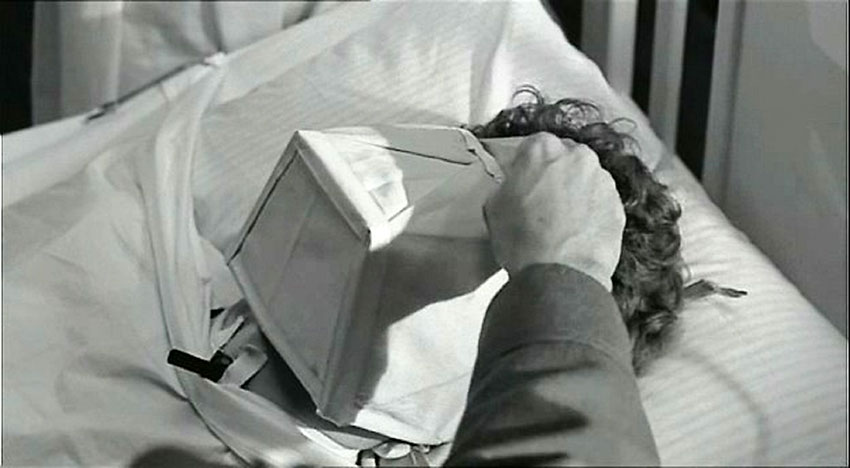

The victim of that explosion, a young soldier named Joe, loses his arms, legs and face. He is kept alive as a medical curiosity, and the officer in charge writes, “It follows, then, that this young man will be as unthinking and unfeeling as the dead until the day he joins them.” That is not the case (if it were, the movie would be different): Joe remembers and dreams and tries to comprehend his present condition. Already the film gives off a considerable stench. Trumbo’s method has always been to take an uncompromising stand (here, against mutilation) in terms so broad and banal that debate is not possible this side of sanity. This speechless basket case is just about the perfect vehicle for the ideas on display, given their quality. Inarticulate movie heroes (The Graduate, Easy Rider) are always in fashion, and how could one hope to improve on this one? Who wouldn’t feel pity for this “piece of meat that keeps on living,” as Joe calls himself; Timothy Bottoms voices him in his debut.

Worse yet, the prevailing cheapness is rendered unendurable by the sentimental muck piled on top of it. The present is shot in black and white, while Joe’s fantasies and memories are in color. “I don’t know whether I’m alive and dreaming or dead and remembering,” Joe thinks at one point, but the film never suggests the lightning-like play of conflicting, misshapen images that statement implies; everything is heavy, plunked down. Many of the scenes come not from Joe’s consciousness but Trumbo’s — the gross gibes at W. W. I slogans (“Gonna make the world safe for democracy, aren’t you?”). The scene in which Joe delicately deflowers his girl may become a model for the protractedly coy and cutesy. Joe’s gradual awareness of his state (“No eyes … I … I haven’t got any eyes!”) is meant to be horribly moving, but it brought Thomas Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy (1587?) to mind:

O eyes! no eyes, but fountains fraught with tears;

O life! no life, but lively form of death;

O world! no world, but mass of public wrongs.

For bombast, the lesser Elizabethans rule. Better (or worse) is the sympathetic nurse, for whom Diane Varsi does her considerable best, hurtling into the grotesque. Joe thinks, “Something fell on me. Something wet. What was it?” A tear. Later she writes “Merry Christmas” on his chest. (I wouldn’t call Trumbo’s touch light.)

Joe eventually hits on the idea of tapping out Morse with the back of his head. The Army brass are astounded, since they would never have allowed him to live if they had thought he wasn’t “decerebrated.” His message to them is “I want out, so people can see what I am. Put me in a carnival show where they can look at me. Let me out.” And then: “If you won’t let people see me, then kill me.” The Army (of course) does neither. Presumably they will not accept responsibility for his present state or for killing him. The friendly nurse tries to kill him but is discovered and sent away. At the end Joe is alive and alone.

One exchange prompted wild applause both times I saw the film. A high-ranking officer asks the chaplain if he has anything to say to Joe. The chaplain answers, “I will pray for him for the rest of my days; but I will not risk testing his faith against your stupidity” — and a great many cheered (the one who applauds loudest hates war the most?). An antiwar film that lets everyone off the hook is by definition a flop. I yield to many in my approval of Godard’s Les Carabiniers, but it is to be commended for its refusal of easy emotional escape-hatches. Johnny Got His Gun sees to it that one leaves with a mind unengaged and assumptions undented. Besides, the tragedy of war is not that perfectly healthy young people are turned into basket cases in a split second; automobile accidents can do that.

George Orwell wrote in 1944: “By shooting at your enemy you are not in the deepest sense wronging him. But by hating him, by inventing lies about him and bringing children up to believe them, by clamouring for unjust peace terms which make further wars inevitable, you are striking not at one perishable generation, but at humanity itself.” If one bothers with antiwar films at all, it should be to learn something we don’t already know, not because we want our sympathies reinforced.

Extra: Timothy Bottoms Interview (2009 Video)

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.