Director: Anthony Harvey

Director: Anthony Harvey

Writers: James Goldman (screenplay), James Goldman (play)

Cinematography: Douglas Slocombe

Music: John Barry

Cast: Peter O’Toole, Katharine Hepburn, Anthony Hopkins, John Castle, Nigel Terry, Timothy Dalton, Jane Merrow

The Lion in Winter – A Look Back

By Walt Mundkowsky

Every chronicle play is a reduction of history. In a great chronicle play, this reduction means compression of events, intensity, selection — an artistic vision of history; Marlowe’s Edward II concentrates 24 years (1307-1330) into five credible acts. The Lion in Winter is another sort of reduction: It diminishes a struggle for the English crown into situation comedy. Since James Goldman wrote the original play as well as the movie script, the inanity of the former is preserved in the latter.

The action takes place at Christmas, 1183. King Henry II of England (Peter O’Toole) decides to name his successor; his wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine (Katharine Hepburn), whom he has imprisoned for 10 years, joins him. So do his sons — Richard the Lion-Hearted, the scheming Geoffrey, and nitwit John. Also present are 17-year-old King Philip of France (Timothy Dalton) and his sister, Princess Alais (Jane Merrow), who is Henry’s mistress. Early on Henry says of Eleanor: “She knows I want John on the throne and I know she wants Richard.” The rest of the film is the clash of their wills. At the end of the holiday nothing has been resolved, and Eleanor is returned to her confinement. Henry tells her, “You know, I hope we never die.” Eleanor: “I hope so, too.” Henry: “You think there’s any chance of it?” The movie ends with both of them laughing boisterously as her barge pulls away.

Problems inherent in this stuff are nearly insuperable; drama in which character is constantly sacrificed to the quip cannot be substantial, especially when both fall as flat as they do here. One-liners like “Has my willow turned to poison oak?” and “Well — what shall we hang? The holly or each other?” are plentiful, and Goldman plops a speech loaded with big ideas into the bitchy infighting (“I’ve found how good it is to write a law or make a tax more fair or sit in judgment to decide which peasant gets a cow. There is, I tell you, nothing more important in the world. (…) I am sick of war”). Modern locutions clang all over — “Fragile I am not; affection is a pressure I can bear.” Goldman’s attempt at history’s verdict sits uneasily, containing as it does a compliment to himself (Henry’s “My life, when it is written, will read better than it lived”).

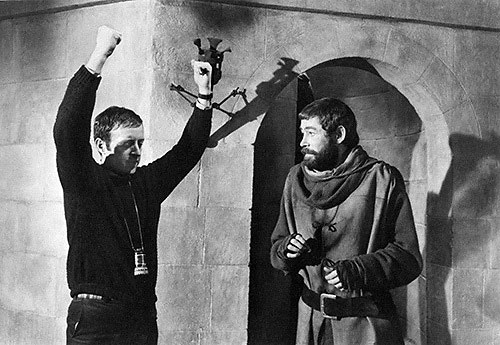

Anthony Harvey’s direction supplies the coup de grâce. His first film, Dutchman (1966), contrived to coarsen the LeRoi Jones play — no small achievement. I cannot imagine how that prepared him for this, but the toolbox of arty clichés runs unchecked. The film opens with a shot of the sky; suddenly crossed swords meet in the frame — cut to a close-up of Henry. “Come for me!” he shouts. As it turns out, he is just dueling with John. Or, after threatening to disinherit all his sons, Henry collapses next to a castle wall, the camera zooming back until he becomes a tiny, almost imperceptible figure. Several scenes begin with burning candles or torches; much of the film has a murky look, as if Harvey is trying to establish a Medieval visual style. Annoying overuse of the zoom lens emphasizes his priorities; the movie isn’t allowed to unfold naturally. The camera zooms in from long shot to close shot, or zooms out from irrelevant close-up (a fist knocking on a door, the beak of a stone bird) to establishing shot, rather than taking us swiftly to the heart of the scene. Sometimes Harvey reminds us of other, better films — the gargoyles in close-up behind the opening titles are not unlike those at the end of A Man for All Seasons. But what worked there — cutting from the sound of the headsman’s axe to the camera tracking silently past darkened gargoyles, accompanied by dry narration — is mere affectation here: unrelated to what follows.

This picture carries the marks of respectability and money. Peter Murton’s art direction and Margaret Furse’s costume design couldn’t be bettered. The music of John Barry has its moments (the opening credits, the choral elements) but is often sticky. A book would be necessary for Douglas Slocombe’s camera triumphs (he passed away in 2016, aged 103). His restrained work for Harvey makes eloquent use of dark, rich colors. I’d put some cornball set-ups on the director. (“May I watch you kiss her?” Eleanor asks. In the foreground, Henry in right profile and Alais in left, facing each other; in the background, Eleanor facing the camera. Henry and Alais embrace. The camera zooms past them into a close-up of the weeping Eleanor.)

O’Toole’s Henry is elusive (many effects, scant continuity or line), with Hepburn always on the verge of bursting into tears, every speech like a lecture. Can an Oscar be far behind? The sons Richard and John aren’t much help, but John Castle makes an adequately oily Geoffrey, perhaps a bit lacking in the “wheels and gears” Henry speaks of. He does contribute a nice touch, however. “Be Richard’s chancellor,” Eleanor proposes. “Rot,” he answers, gliding away. I have never heard a more mellifluous “Rot.”

To escape the continual racket from the leads, we turn to Jane Merrow’s Alais, a gentle creature fiercely refusing to be used by anyone. Her pleas to her lover (“You mustn’t play with feelings, Henry. Not with mine”) and to his wife (“You love Henry but you love his kingdom, too. You look at him and you see cities, acreage, coastline, taxes. All I see is Henry. Leave him to me, can’t you?”) touch us if not her listeners. Timothy Dalton is her equal as the young French king. His part is small but multi-faceted — unsure of himself on the surface (“I am a king; I’m no man’s boy”) but possessing a natural gift for intrigue, cold and calculating beyond his years. Had the whole enterprise been infused with the feeling and smarts of Dalton’s acting, we’d have something.

I’ll take O’Toole’s “Henry II, Part I” by no great margin. That would be Becket (1964).

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.

Raoul

November 20, 2021 at 2:26 am

I watched TheLion in Winter when it first ran in the cinema. Because of your review I decided to watch this movie again. I remember being so impressed by the acting —- the constant bickering, the free exchange of daggered insults, often the point of the dialogue would escape me. Your review helped me understand what was happening.

It’s true. Artistic license condensed years into moments. I wonder if the family.s sexual activities were conjured up. Essentially, you exposed the film for what it is—- a historical fiction: a playground backdrop for actors and juicy dialogue writers to display their talents.

If you take the film for what it is, it really isn’t too bad.

I do have to commend your prose and knowledge of film production technique. It’s obvious you are a child of the theater arts. Makes me wonder what kind of a director you could have been. Keep up the good reviews!

Gunnar

November 23, 2021 at 5:22 am

Another online review of this film points out over and over again why it’s SUPERB, and I agree, it is. Then again, when Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony premiered, it TOO got bad reviews.