Directed by: Joseph Losey

Directed by: Joseph Losey

Screenplay: Harold Pinter

Based on the novel: “The Go-Between” by L.P. Hartley

Cast: Julie Christie, Alan Bates, Margaret Leighton, Michael Redgrave, Dominic Guard, Edward Fox, Jim Broadbent (Uncredited: Spectator at cricket match)

Cinematography: Gerry Fisher

Music: Michel Legrand

Losey’s The Go-Between

Walt Mundkowsky

The Go-Between (1971, Columbia) is the third film Joseph Losey has directed from a Harold Pinter script. Its virtues and defects are so much those of the first two (The Servant, 1963, and Accident, 1967) that Pauline Kael’s judgment on Accident fits — “a fascinating, rather preposterous movie, uneven, unsatisfying, but with virtuoso passages of calculated meanness.”

This film is an intelligent, respectful adaptation of the 1953 novel by L.P. Hartley, which Martin Esslin has called, rather excessively, “a minor classic and a masterpiece.” Henry James comes to mind (he would have deepened the psychological implications), but Hartley possesses his own vision and tone of voice. The story is simple enough. During the summer of 1900, a middle-class schoolboy named Leo Colston spends three weeks with the family of his friend, Marcus Maudsley. Leo forms a crush on Marian, Marcus’ beautiful older sister, and comes to serve as messenger in her affair with Ted Burgess, a neighboring tenant farmer. On Leo’s 13th birthday the affair is discovered and Ted shoots himself.

An extraordinary passage illustrates, I think, what the novel is about: “Something of the sadness of human life came through to me, its indifference to our wishes, even to the wish that calamity should be more colourful than it is. The ideas of acceptance and resignation were hard for me to entertain: I thought that emotions should be more dramatic than the facts that caused them.” The movie never finds its way to that, but the concise beauty of Hartley’s prose would resist translation in any case. Nearly all of Pinter’s dialogue is from the book, much condensed. This process of selection doesn’t reduce the novel to its essence, it strips the story of its first-person viewpoint and that elaborate psychology.

Two scenes will suffice. The cricket match is shot and edited with surging exactness, but fails to symbolize the larger issues which inform the novel (“a struggle between order and lawlessness, between obedience to tradition and defiance of it … between one attitude to life and another”). At the supper after the match Leo sings Handel’s “Angels, ever bright and fair” — “I was proud of being able to sing it, for it was in the most uncompromising minor and the intervals were very tricky….” In the film Leo, in one long close-up, butchers the song. Losey discards the original point — “the sensation of soaring that the music’s slow ascent so powerfully evoked” — in favor of a cheap laugh.

Losey admires Resnais, and the handling of time sets the film apart from the novel most strongly. In the book Leo, in his mid-sixties, comes across the diary he kept during 1900. He narrates the story in the past, from the vantage point of the present. In the epilogue he returns to Brandham Hall to find out what has happened in the intervening 50 years; he visits Marian, now a very old woman. Losey has dropped the prologue, and throughout the film he slips in flashes of Leo’s journey to the past we see; the fragments are jumbled, but as they lengthen the design becomes clear: The whole movie is a careful build-up to Leo’s meeting with Marian in the present. Clearly Losey has learned from Hiroshima mon amour and La guerre est finie: the juxtaposition of seemingly unrelated image and sound, a soundtrack from the present over visuals from the past and vice versa, the flash-forward technique. As is usually the case except for Resnais, it works better in theory than in practice. Leo and Marian are riding along in a carriage and we hear Leo as an old man, “You flew too near the sun and you were scorched.” The line is drawn from a lovely conversation in the book between Leo at 12 and Leo at 60-odd. Used alone, it is too blatantly ominous, as are the flashes-forward — overcast, rainy skies; a black limousine gliding about; the trick of nearly always showing Leo with his back to the camera.

As in The Servant and Accident, a pivotal female role in The Go-Between is badly cast and acted. Julie Christie, as Marian, is not believably upper-class for an instant, and at 31 is too old for the part anyway. Richard Gibson’s Marcus likewise fails to persuade; Losey has no feeling for the nuances and ever-changing hostilities of the boys’ repartee and scuffling, which play an important role in the book. Usually Losey pays great attention to the music in his films. Here he has entrusted the score to Michel Legrand, who produces a series of formal pieces for piano and strings — devoid of any period sense and startlingly indelicate.

As in The Servant and Accident, a pivotal female role in The Go-Between is badly cast and acted. Julie Christie, as Marian, is not believably upper-class for an instant, and at 31 is too old for the part anyway. Richard Gibson’s Marcus likewise fails to persuade; Losey has no feeling for the nuances and ever-changing hostilities of the boys’ repartee and scuffling, which play an important role in the book. Usually Losey pays great attention to the music in his films. Here he has entrusted the score to Michel Legrand, who produces a series of formal pieces for piano and strings — devoid of any period sense and startlingly indelicate.

Some of the goings-on are resolutely clouded. Leo fancies himself a magician; the novel treats his experiments with a touch of amusement after the passage of so many years. The film, however, strains to make them vaguely menacing — its sole “Pinteresque” touch. When Leo tries “to break the spell that Ted had cast on Marian,” the obscurity gets so thick that it’s impossible to tell what, if anything, is happening. Fundamental events like Leo’s last meeting with Marian are presented in needlessly puzzling fashion — Julie Christie’s dubbed-in old-lady voice; the watery blues of the photography; the off-center editing, which focuses on Leo even though he says hardly anything. Hartley’s effect is missed by a mile: “A foreigner in the world of the emotions, ignorant of their language but compelled to listen to it, I turned into the street. With every step I marvelled more at the extent of Marian’s self-deception.” A worthy theme — the primitive cruelties hidden behind civilized gestures — but Losey and Pinter dissect the class humiliations and general rot with a relish that makes their work part of what they are attacking. Distinctions get blurred.

Still, The Go-Between has undeniable if finally insufficient strengths. The film retains Hartley’s unforgettable opening line, “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there,” and its finest achievement is the way it charts that alien ground. Carmen Dillon, the art director whose work on the contemporary Accident was so meticulously right and revealing, makes Brandham Hall and its surroundings perfectly convincing to the last detail. This is not just a question of historical authenticity — not very difficult to arrange — but a matter of choosing the most unobtrusively striking facets of décor. Ms. Dillon succeeds; if you remember anything about this film, it is likely to be the setting.

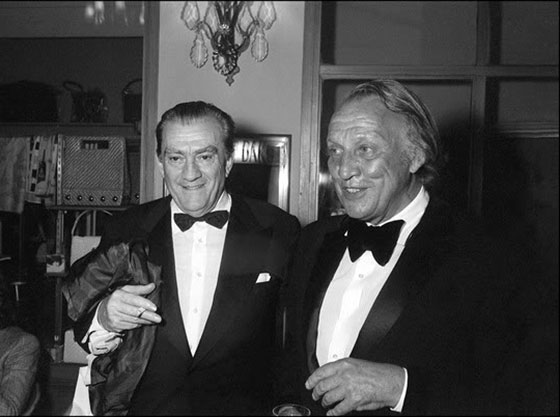

Joseph Losey (right) was the recipient of the Palme d’Or for The Go-Between at 1971 Cannes Film

Joseph Losey (right) was the recipient of the Palme d’Or for The Go-Between at 1971 Cannes Film

Festival. To his left, Luchino Visconti, whose film Death in Venice was also in competition.

In this she is aided by Gerry Fisher. Accident was his debut as lighting cameraman — and an impressive triumph; in the five years since, he has established himself as one of the more expert and tasteful color cinematographers. It’s hard to see how he could have gone wrong among all those costumes and the Norfolk countryside. The outdoor scenes could be further removed from mere prettiness, and on Leo’s trips between the Hall and the farm the zoom lens gets tedious (Leo trying to outrun the music?). But the interiors are splendid: The colors are toned down to the neutral range — beiges, soft browns and greys — and are properly seductive.

Losey is often skilled with actors and these performances are first-rate (exceptions noted). Best of all is Dominic Guard. The director has exploited the stiffness and unease of the inexperienced child actor to great advantage; Leo is a stranger who feels out of place. He is awkwardly anxious to please, with an edgy hostility beneath the surface. Guard gives the film what cohesion it has. Alan Bates works admirably against the Lawrentian mist Losey tries to throw around Ted, but the result is no more than the standard Bates performance.

The aristocrats receive more attention, scornful though it may be. Margaret Leighton is a faultless Mrs. Maudsley; when she questions Leo about the letters he has been carrying for Marian, the cloak of politeness drops off and we see the fury which has been lurking all along. The actress manages the transitions so subtly that we are as shocked as Leo. As her ineffectual husband, Michael Gough has the correct bearing and voice. His dialogue is amusing, verging at times on caricature. Edward Fox (his brother James was the young master in The Servant) plays Viscount Trimingham with nonchalant grace and sure technique. He captures especially well Trimingham’s relationship with Leo, alternating between genuine interest — treating him almost as an equal — and lofty, tolerant condescension.

Losey and Pinter are up to the casual destruction of Leo’s innocence; they fall short of the sharp feeling of loss Hartley creates. In the prologue Leo thinks that “had it not been for the diary, or what the diary stood for, everything would be different. I should not be sitting in this drab, flowerless room, where the curtains were not even drawn to hide the cold rain beating on the windows, or contemplating the accumulation of the past and the duty it imposed on me to sort it out.”

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.

Thomas Yotka

May 31, 2022 at 10:50 am

In answer to Mr. Mundkowsky’s review I think I will leave it to Leslie Hartley to respond, via his letter of

February 4, 1969 letter to screenwriter Harold Pinter:

“After much tribulation with my proofs I have now finished your script of The Go-Between.

It is absolutely splendid – and more faithful to the letter and spirit of the book than I could have

believed possible – seeing that there are bound to be changes in translating a work from one medium

to another.

You needn’t have said ‘based’ on ‘The Go-Between’ –

for it IS The Go-Between ! – the essence of it.

The dialogue, which I thought might sound old-fashioned, you have somehow,

without altering it appreciably, given an infusion of new life, or perhaps just

TIMELESSNESS. And the emotion of the story come through at every word –

I wept at the scene where Leo questions Ted about ‘spooning’ – which is more

than I did when I wrote my version of it.

To have condensed to much, without ever losing – rather, with enhancing and

pin-pointing (if one can use such an expression) the essentials of it, is indeed

a triumph.”

Now perhaps Mr. Mundkowsky will reply, “Well, L.P. Hartley doesn’t know what

HIS novel really is about, and neither do the film-makers.”

But some us who have enjoyed this film for the last 50 years may offer the polite

but firm counter: NO, Mr. Mundkowsky, it is YOU who are “talking through

your hat”.