Today’s headlines are still ablaze with news of rage and protests, which began with the savage killing of African-American George Floyd at the knee of white Minneapolis police officer, Derek Chauvin, now convicted for murder. Yes, White Lives Matter when Black Lives Matter, too. And now our great nation holds its breathe as we attempt to defend our experiment in Jeffersonian Democracy and Justice for All. The following article appeared in Traveling Boy over ten years ago, after a press trip to Tulsa and the Cherokee Nation, when many U.S. citizens were unaware of the worst race massacre in American history. And now, thanks to 60 minutes’ May 30 broadcast of the tragedy, the news has spread to the far corners of our nation.

At the time of my trip to Tulsa, this tragic event was so secretive that my thoughtful guide in Oklahoma knew nothing about it, and I had to direct him to its site. It remains the worst race massacre in U.S. history.

The time and place: The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre

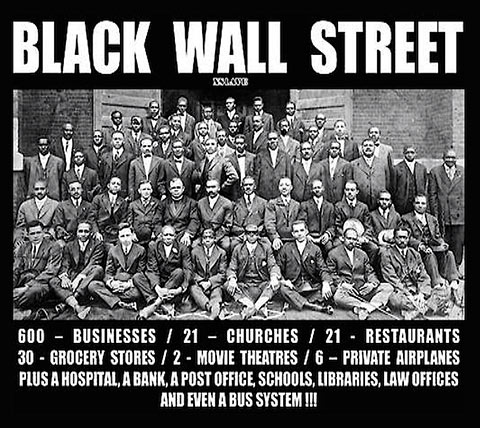

Tulsa’s Greenwood District was once an affluent African-American community, nationally known as the Black Wall Street. During the segregated Jim Crow era of the 1920’s, most of Tulsa’s 10,000 African-American residents lived in Greenwood, which included 300 black-owned businesses, a thriving financial district, post office, churches, middle and upper-class homes, nationally-known doctors, lawyers, bankers, and, yes, millionaires.

It was a model self-contained city, where citizens conducted their lives in harmony; devoid of racism and harassment. Residents could no longer be denied patronizing movie theaters, concerts, restaurants and stores. They had become a living example of what all Americans should be: first-class citizens. All this took place in the affluent 300 black-owned businesses of Greenwood.

BUT, THINGS WERE ABOUT TO CHANGE

Due to a still dubious claim by a white female elevator operator that a black 19-year-old shoe shiner, Dick Rowland, did ‘something’ to offend her in the elevator (still a mystery today), Rowland was immediately arrested and sent to jail. Rumors of what had supposedly happened began to circulate throughout the city’s white community. That afternoon a front-page story in the Tulsa Tribune enraged some of the white populace with the report that the police had arrested a ‘Negro’ man for sexually assaulting a white woman.

News spread like California wildfire. When a white mob gathered at the jail, Rowland was moved from the city jail to the more secure county lockup on the top floor of the city’s courthouse. Growing numbers of the white mob, now estimated at 2,000, marched to the courthouse, demanding Rowland to be lynched. Enraged by the countless lynchings in the past, truckloads of armed African-Americans from the Greenwood District arrived to stop it. When the white mob attempted to storm the building, Sheriff Willard McCullough and his deputies heroically dispersed the crowd, protecting Dick Rowland from death. Later that night, there was a struggle between a member of the white lynch mob and an African-American man from Greenwood with a gun. As they wrestled for the gun, it accidentally went off, killing the white man. This incensed the mob to a boiling point.

As one man observed, All hell is about to break loose!

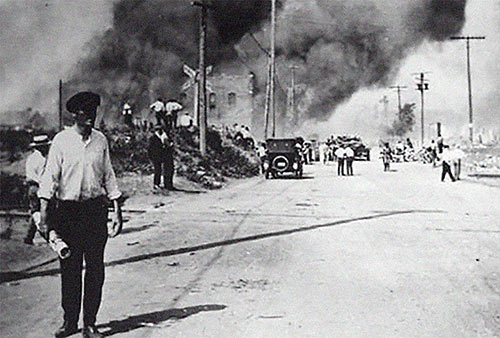

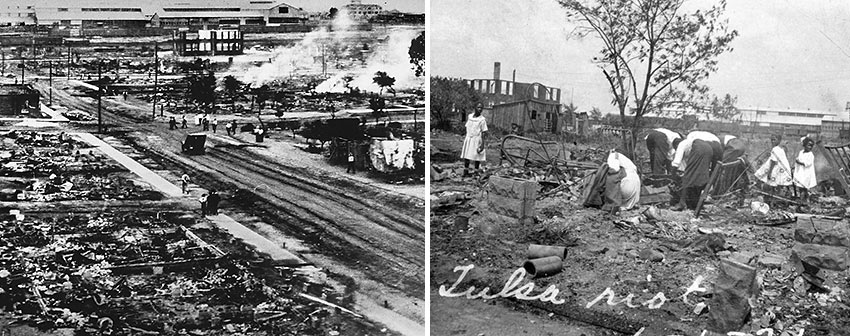

In the following early morning hours of June 1, 1921, vigilante mobs of white rioters poured into the Greenwood District; killing, looting and burning all 35-blocks to the ground. The city government of Tulsa conspired with the mob, arresting more than 6,000 black residents and refusing to provide them with protection or assistance. Law enforcement officials used airplanes to drop firebombs on buildings, homes and fleeing families; stating they were protecting the city against a “Negro uprising.” An African-American World War l veteran put on his uniform in an attempt to show the white rioters that he was a loyal American, but received deadly bullet holes in his uniform as a reply. The nationally renowned physician, Dr. A.C. Jackson, was murdered when he approached the blood-thirsty mob with his arms raised. Over 6,000 African-American citizens were imprisoned, and some historians believe as many as 300 African-Americans, including women and children, were massacred, while thousands were left homeless. Many of the dead were then dumped into unmarked graves. News reports were largely squelched. Until a year ago it was difficult to find any mention of the worst U.S. incident of racial violence in any national public school history books, Oklahoma classrooms or even in private conversations. In April 2002, a private religious charity, the Tulsa Metropolitan Ministry, paid a total of $28,000 to the known survivors, a little more than $200 each, using funds raised from private donations.

The Tulsa Race Riot still remains the worst incident of racial violence in U.S. history. Thankfully, the modest Greenwood Cultural Center (formed in the late 1970s) is keeping this tragedy alive today. Their mission is to preserve African-American heritage and promote positive images of the African-American community by providing educational and cultural experiences promoting intercultural exchange, and encouraging cultural tourism. May God Bless Them.

Epilogue:

Excerpts courtesy of 60 Minutes, May 30, 2021.

In Tulsa, it is a debate that has continued for nearly a century, as May 31-June 1 marks 100 years since the massacre occurred there. Until recently, the memory of what happened in Tulsa’s Greenwood neighborhood had been buried with its victims. Today, exhuming the city’s past also means confronting its present.

When 60 Minutes producer Nicole Young and correspondent Scott Pelley set out to tell the story of the Greenwood massacre for this week’s broadcast, they visited the Vernon AME Church. In 1921, the mob had burned the church, leaving only its basement intact. Once the smoke cleared, Greenwood residents returned to that basement to resume worship, and as the community rebuilt, the church became its spiritual heart.

At the church in December 2019, Young and Pelley assembled members of the congregation and asked them to tell the oral histories they had learned about Greenwood from generations past. Many people said their families had been afraid to speak of the massacre, for fear of retribution.

“They didn’t talk about it in our family,” said Therese Anderson Adoonie, a Tulsa resident. “But what I do know is that my father grew up watching them rebuild from ashes.”

Among those who had gathered to tell their ancestors’ stories was Rev. Joey Crutcher, whose grandmother had survived the Greenwood massacre before fleeing Tulsa. Almost a century later, Crutcher’s son, Terence, was shot dead by a White police officer in the same city.

In 2016, Betty Jo Shelby fatally shot Terence Crutcher as he was standing next to his vehicle in the middle of a street. He was unarmed. Although a jury later acquitted Shelby, who went on to work as a deputy sheriff in neighboring Rogers County, and has since retired, the shooting spurred protests and renewed a national debate over race and policing.

“There was absolutely no justification whatsoever, with all the backup, for Officer Shelby to pull that trigger,” Tiffany Crutcher, Terence’s sister, told 60 Minutes’ Bill Whitaker in 2017. Just as Crutcher’s death drove people to the street in protest, the murder of George Floyd in the hands of Minneapolis police last May once again inflamed the conversation about police violence and racial bias. In Tulsa, it is a debate that has continued for nearly a century, as next week (May 31-June 1) marks 100 years since the massacre occurred there.

“Tulsa still has a deep racial divide,” 60 Minutes’ Young said. “You still have a Black side of Tulsa. You still have a White side of Tulsa. There’s still a railroad track dividing both sides of the town and a highway that was built in the ’60s right through Greenwood.”

After Floyd’s death last Memorial Day—the same week the Tulsa race massacre occurred 99 100 years ago—the Rev. Robert Turner of Vernon AME church led a protest through Tulsa to remember Black Americans who have been killed. The crowd chanted Terence Crutcher’s name, among others, “whose lives were taken by racists in power—their perpetrators not brought to justice,” Rev. Turner wrote in a statement.

In Tulsa, long-sought justice was the focus in October as another test excavation began searching for the remains of the victims murdered 100 years ago. The excavation revealed a mass grave with at least 12 individuals, although determining the cause of death is complicated because of that period’s Spanish Flu pandemic. A full excavation and exhumation begin next month, and the next steps include recommendations for a permanent burial and the question of how to honor those who have waited a century for Justice.

“The massacre was always important, which is why 60 Minutes was there,” explained 60 Minutes producer Nicole Young. “But now, seeing the heartache of a nation, of a community, of a people, understanding the dark history of America in all its ugly forms, all of the hard conversations are more important now than they ever have been.”

Other Major U.S. Race Riots and Massacres

New York City Draft Riots (July 13–16, 1863) began when the Union Army began conscripting citizens for military service, but if a payment of $300 could be made (worth about $9,000 now), then conscription could be avoided. Manhattan’s wealthy could buy their way out of military service, while the city’s poorer immigrant population, mostly from Ireland, could not. The protests exploded into a race riot, with primarily Irish immigrants focusing their rage on an easy target: Manhattan’s African-American citizens. The official toll was listed at 120 deaths. The military did not reach the city until the second day of rioting, by which time the mobs had ransacked or destroyed numerous public buildings, two Protestant churches, the homes of various abolitionists or sympathizers, many African-American homes, and the Colored Orphan Asylum, which was burned to the ground. Numerous black residents fled Manhattan permanently.

The Atlanta Race Riot (Sept. 22-24, 1906): The Atlanta Race Riot of 1906 made headline news throughout Europe and the Americas for its especially brutal character. The race riot was an attack by armed mobs of white Americans against African-Americans in Atlanta, Georgia. According to the Atlanta History Center, some black Americans were hanged from lampposts; others were shot, beaten or stabbed to death as white mobs invaded black neighborhoods, destroying homes and businesses. The immediate catalyst was newspaper reports of four white women raped in separate incidents, allegedly by African-American men. An underlying cause was the growing racial tension in a rapidly-changing city and economy, with competition for jobs, housing, and political power.

The Detroit Race Riot of 1943 (June 20-22, 1943): Detroit’s three-days of rioting was the result of racial tensions between migrated blacks from the U.S. Rural South and migrated whites also from the U.S. Rural South, who had both arrived in the industrialized North for better opportunities. As they competed for jobs against one another, the situation intensified, leading to the bloodiest and costliest race riot of 1943. Thirty-four people died and about 1,800 were arrested. Detroit’s auto industry was, at the time of the riots, churning out machines for the Allies’ war effort, and while the riots didn’t affect production, the Japanese Imperial Empire used the incident as propaganda, and called on American blacks to not participate in the war effort against the Axis.

Los Angeles Rodney King Riots, (April 29-May 4, 1992): The brutal beating of African-American Rodney King, and the subsequent acquittal of the LAPD officers for that beating (which was caught on camera) led to the worst riot in the United States since the late 1960s. The reaction to the acquittal in South Central Los Angeles — now known as South Los Angeles — was then an area where more than half of the population were black. Tension had already been mounting in the neighborhood in the years leading up to the riots: the unemployment rate was about 50 percent, a drug epidemic was ravaging the area, and gang activity and violent crime were high.

Olivia Hooker: Tulsa Race Riot Survivor Dies Aged 103

Courtesy BBC World News

When Olivia Hooker was six years old, she was forced to hide under a table as a white mob destroyed the neighborhood around her. Later, she would recount how she struggled to stay silent as the torch-carrying men took an axe to the family piano. Outside, as many as 1,000 homes and businesses – including her father’s clothes store – were being reduced to rubble.

The 1921 Tulsa race riot would also leave as many as 300 black people dead. But the horrifying incident in Oklahoma would be far from the only distinguishing moment of Ms Hooker’s remarkable life.

In her 103 years, she would become the first African-American woman to join the US Coast Guard, go on to gain a PhD and eventually play a key role in pursuing justice for the victims of the race riot, more than 70 years after the fact. She would be praised as a “tireless voice for justice and equality” by America’s first black president, and called “a national treasure” by the head of the US Coast Guard.

Read her full story here