Directed by: Gillo Pontecorvo

Directed by: Gillo Pontecorvo

Writing Credits: Franco Solinas and Gillo Pontecorvo

Music by: Ennio Morricone and Gillo Pontecorvo

Cinematography by: Marcello Gatti

Cast: Brahim Hadjadj, Jean Martin, Yacef Saadi

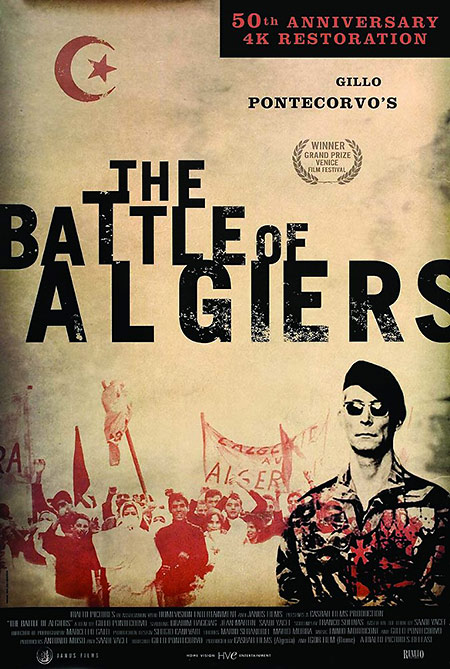

The Battle of Algiers

By Walt Mundkowsky

Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers (Allied Artists) was the hit of the 1966 Venice Film Festival and enjoyed a highly successful run in New York the following year. The film would be welcome at any time; considering the junk we have been asked to watch so far this year, it is an especially great pleasure.

The title is apt. In the main, this is a reconstruction of the street fighting in Algiers between 1954 and 1957 (a coda informs us of Algerian independence on July 2, 1962). The film should not be taken in any way as a record of the Algerian struggle: Virtually no mention is made of the fighting in the mountains or of political developments in Paris, both of which were at least as significant as what we are shown. But Pontecorvo and screenwriter Franco Solinas have generally chosen well. Their focus on a single facet of the conflict illuminates some complex recent events.

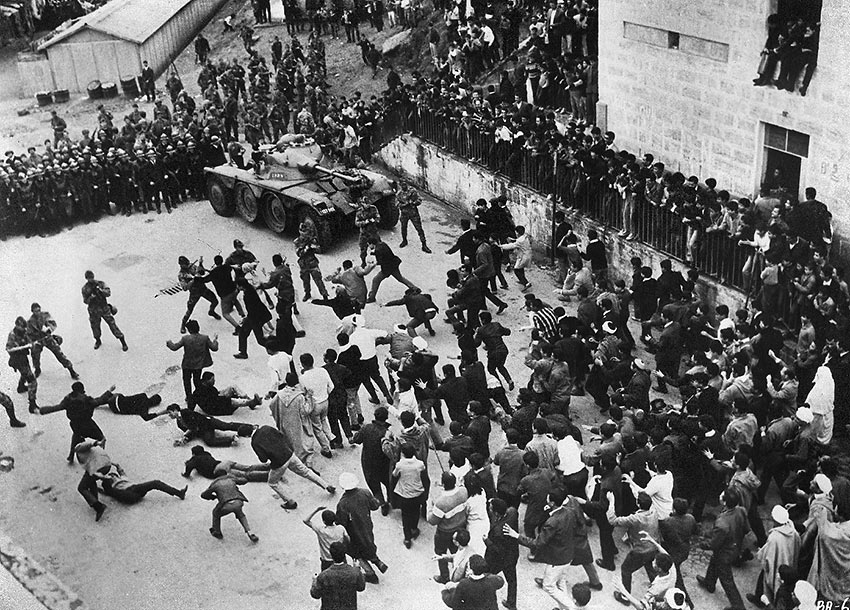

Hardly anyone has failed to notice that The Battle of Algiers has been made to resemble a newsreel. Marcello Gatti’s black-and-white photography is the best of its kind I can remember. The quasi-documentary look, with its graininess, subdued tones and functional, sometimes hand-held set-ups, is contrasted with sweeping camera movements of beauty, elegance and wit. Which is to say that I’ll never see newsreels of such refinement. Gatti does a brilliant job of photographing walls: The sunlight that so captivated Camus is more powerfully conveyed than in the film of The Stranger. The editing of the Marios Serandrei and Morra is blessedly free of special pleading and wearying, grubby little touches; image and sound are matched or counterpointed with imagination, and no sequence is permitted to overstay its welcome. Each makes its point and departs. The almost entirely non-professional cast does not act its roles, it inhabits them.

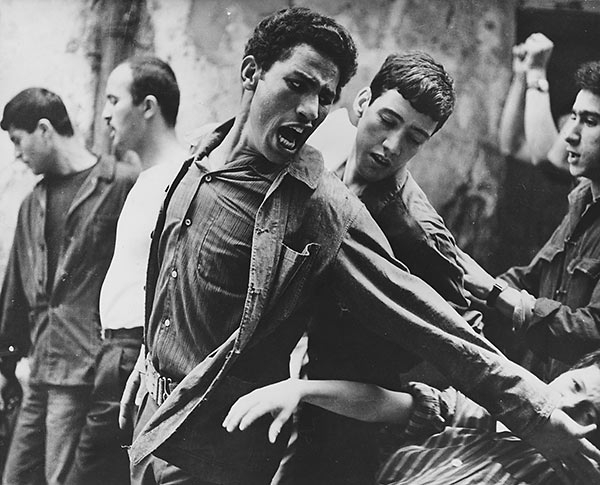

Front de Libération Nationale rebels are individuals; their leaders’ understanding of the situation varies widely, from those who appreciate the political difficulties to Ali la Pointe, an illiterate petty crook who advances to FLN section head and just wants to kill Frenchmen. Two of these actors must be mentioned. The rebel boss is played by Yacef Saadi, the film’s Algerian co-producer and an actual FLN leader condemned to death three times by the French and saved by de Gaulle’s general amnesty. Brahim Haggiag radiates fanaticism as Ali; truly a man on fire.

Front de Libération Nationale rebels are individuals; their leaders’ understanding of the situation varies widely, from those who appreciate the political difficulties to Ali la Pointe, an illiterate petty crook who advances to FLN section head and just wants to kill Frenchmen. Two of these actors must be mentioned. The rebel boss is played by Yacef Saadi, the film’s Algerian co-producer and an actual FLN leader condemned to death three times by the French and saved by de Gaulle’s general amnesty. Brahim Haggiag radiates fanaticism as Ali; truly a man on fire.

Pontecorvo gets the main facts right, as far as I can tell. After the FLN organizes, it embarks on a string of terrorist acts, indiscriminate murders of policemen. The first plastique bomb is exploded by the French; a police commissioner, in misplaced revenge against the rebels, sets it off after curfew in the Casbah. The FLN replies by exploding three bombs in the French sector — in a crowded café, an equally jammed milk bar and an air terminal. (Here the film cheats a little. The rebel bombings are made to appear a reflex action; in fact, they took place two months after the first bomb, when no arrests were made.) Pontecorvo’s point is that wars of liberation, while inevitable, leave only victims; that the victims of Arab bombs and French bullets are equally dead. Justice and history may be on the side of the rebels, but it is tough for him to see past the corpses piling up.

The impact of the film derives from the way Pontecorvo implicates us in the drama. Each terrorist killing is prefaced with a title giving the exact time of day; thus we are elevated from unknowing onlookers almost to accomplices. As the final seconds tick by, the exquisitely caught and edited shots are agony to behold: a little boy licking an ice cream cone and having his face wiped, lovers at a table, teenagers dancing, the white-coated man behind the counter laughing. A young girl is carried out after the explosion. At first all we can see of her are long legs and chic shoes; then the front of her stylish dress bobs into view, soaked with blood. Gripping, natural detail inhabits Pontecorvo’s direction throughout. Frequent use of those modern clichés, the freeze-frame and zoom lens, is fresh and valid.

But it would be just a superior historical re-creation without the French paratroop commander, Lt. Col. Philippe Mathieu. I do not know how much the part owes to the famous Lt. Col. Trinquier and how much is fiction, but the result is rich and complex. Mathieu is played by the one professional actor, Jean Martin, well known in Paris for his work in Beckett, Ionesco and Pinter plays; he never makes a wrong move in this long and demanding role. The colonel learns that the FLN structure is pyramidal: Each rebel knows the identity of only three others, his superior and his own pair of subordinates. They have been ordered to remain silent for 24 hours after capture, after which their information is useless. “But interrogation is a method only when it guarantees a reply,” Mathieu tells his officers. Mathieu is no brute, but a learned and sensitive man who stops to pay tribute to the moral force of his enemy. His wit is irreverent and almost self-deprecating. (“Checking identification is ridiculous. If anyone’s papers are in order, it’s the terrorists’!”) He grasps the FLN tactics (“Bombs make more noise; in the FLN’s place, I’d use them”) and defends his own — “Does bombing in public places show respect for legality? It’s a vicious circle.” Mathieu asks a reporter, “Why are the Sartres always against us?” and the question says everything about him. A few exchanges make plain the French military’s obsession with avoiding another Dienbienphu. But as a captured FLN leader says, “The FLN has a much better chance of beating the French army than the army has of changing history.” For Mathieu, it can be reduced to an epigram: “Our duty is to win.”

But it would be just a superior historical re-creation without the French paratroop commander, Lt. Col. Philippe Mathieu. I do not know how much the part owes to the famous Lt. Col. Trinquier and how much is fiction, but the result is rich and complex. Mathieu is played by the one professional actor, Jean Martin, well known in Paris for his work in Beckett, Ionesco and Pinter plays; he never makes a wrong move in this long and demanding role. The colonel learns that the FLN structure is pyramidal: Each rebel knows the identity of only three others, his superior and his own pair of subordinates. They have been ordered to remain silent for 24 hours after capture, after which their information is useless. “But interrogation is a method only when it guarantees a reply,” Mathieu tells his officers. Mathieu is no brute, but a learned and sensitive man who stops to pay tribute to the moral force of his enemy. His wit is irreverent and almost self-deprecating. (“Checking identification is ridiculous. If anyone’s papers are in order, it’s the terrorists’!”) He grasps the FLN tactics (“Bombs make more noise; in the FLN’s place, I’d use them”) and defends his own — “Does bombing in public places show respect for legality? It’s a vicious circle.” Mathieu asks a reporter, “Why are the Sartres always against us?” and the question says everything about him. A few exchanges make plain the French military’s obsession with avoiding another Dienbienphu. But as a captured FLN leader says, “The FLN has a much better chance of beating the French army than the army has of changing history.” For Mathieu, it can be reduced to an epigram: “Our duty is to win.”

Few films can have benefited from music choices like this one — it’s essentially an interplay of image and music; the text is less important. The soundtrack strikes a fine balance between natural and created sound. The music, by Ennio Morricone and Pontecorvo, consists of four modes: taut, rattling sections over the French attacks, scored for snare drums and piano; a tinny little martial tune for Mathieu’s briefings; fervid Arab drumbeats for the FLN bombings; and formal religioso pieces for the torture scenes and bombing aftermath. All stirring and appropriate. Pontecorvo seems to have composed the film with this music in mind, instead of tacking it on as an afterthought.

I have a few qualms. It never puts on the heat and tries to con us the way Costa-Gavras does, and of course it is worlds better than that. The savage ironies of recent history are respected, but still one occasionally wants to shout at the screen, “It wasn’t that simple!” The film does romanticize these events a bit, particularly in light of post-independence Algeria: All that heroism and blood gone to produce Ben Bella and Boumedienne! Still, warts of perspective aside, the film is warmly human and wondrously alive.

Editor’s note: The George W. Bush administration studied The Battle of Algiers in an attempt to understand terrorist tactics and guerrilla warfare in Iraq.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.

Walt Mundkowsky was born 1944 in San Antonio, TX. In his teens he had a dachshund named for German composer Hugo Wolf. Extensive writings on film (1968-72 freelance, a “Cinema Obscura” column in Home Theater, 1995-2001). He favors the mine-shaft approach — in-depth exploration of tiny, unrelated areas. Now a resident of Koreatown in L.A., he has lived in basements in Denver, London and Stockholm, and may very well do so again.